SAILING EVOLUTION

On board Royal Huisman's 47-metre sailing yacht Nilaya

A client’s brief for the new 47-metre Nilaya was so advanced and specific that it ushered in new building methods at Royal Huisman. Marilyn Mower explores her featherlight construction and innovations

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

The path to building the new Nilaya began with a years-long refinement of ideas. The subject under consideration was how to replace a 34-metre high-performance cruiser delivered by Baltic in 2010, a boat with plenty of podium finishes and many miles of family cruising over 12 years. This would be, in other words, the difficult follow-up to a smash hit.

“My brief for the new Nilaya was that she should be versatile, comfortable and safe; a yacht conceived for worldwide cruising in style, yet capable of hitting important racing targets. I wanted her to be fast in light winds, enabling us to cruise without an engine as much as possible,” the owner says.

She can rightly be called a development of her predecessor, with a similar racy, low profile, straight bow and wide transom. But with 2.48 more metres of beam and 13 metres more of length, the increase in interior volume and on-deck living area is immense.

The owners wanted a lot, some of it difficult to reconcile: the capability for longer journeys without sacrificing speed, and a quieter, stiffer boat. They laid this problem at the feet of their team, California-based naval architects Reichel/Pugh and Nauta Design of Milan, who, along with owner representative Nigel Ingram of MCM, had created the previous Nilaya.

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

Nilaya is the most advanced sailing yacht that Royal Huisman has delivered. Her build was a three-year process – a year of preparation

The owners’ emphasis on comfort for this Panamax sloop pushed Reichel/Pugh to collect data on wave heights, wave periods and wave and wind direction in cruising areas on both sides of the Atlantic.

They did this, says naval architect Jim Pugh, not so much for sailing but for comfort while motoring, which happens a lot during Mediterranean summers.

The endgame was to work out weight distribution and an underwater profile that would deliver comfortable passages. After design studies in both carbon and aluminium, and optimisation via computational fluid dynamics, Reichel/Pugh proposed tank testing 12 models.

NICO MARTÍNEZ FOR STUDIO BORLENGHI

NICO MARTÍNEZ FOR STUDIO BORLENGHI

“Our initial recommendation was for carbon fibre,” Nauta co-founder Mario Pedol says. “I came to this project thinking that aluminium construction would weigh 60 to 70 per cent more than carbon.

But at the same time we knew the owner was determined to have a long-range cruising boat with all the amenities expected on a superyacht and for it to be much quieter than typically achievable with carbon fibre.”

Sound and vibration isolation involves weight, so it would come down to setting priorities. The owners couldn’t have it both ways.

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

Or maybe they could. Royal Huisman, which was very keen to bid on the project, suggested the answer was not either/or but both. Huisman began adding carbon-fibre elements to its aluminium yachts in 1997.

Nilaya’s owner, who knew the builder’s attention to superyacht quality, was intrigued, and directed the three parties to explore a hybrid carbon/aluminium solution.

To achieve the low weight required for performance under sail or power, Royal Huisman knew the answer was not just a matter of popping a carbon-fibre coachroof atop an aluminium hull.

It called on the engineering and materials expertise of its sister company Rondal and worked with European Space Agency technology on detailed finite element analysis (FEA) to investigate every possible area of the hull, deck and interior for strength-to-weight ratios, while recalling that comfort was an equal part of the equation.

FEA modelling guided the choice of carbon fibre, varied Alustar plate thicknesses and frame spacing to maximise hull stiffness while minimising total displacement.

In some cases, carbon fibre would be bonded to aluminium to increase its stiffness without adding much weight or bulk. Utilising in-house parametric software to evaluate various structural designs, the builder found major weight savings by using carbon or carbon/aluminium hybrid sections for the door frames, hatches and deck.

Tapering the top of the mast saved 50 kilograms. Rethinking the HVAC system saved 600 kilograms... and so it went

Reichel/Pugh, Royal Huisman and Ingram calculated weights and balances nearly frame by frame to guarantee the best motion under way.

If carbon could replace metal in a way that made sense, it was subjected to a cost-benefit analysis, and if the increased costs of moulding a carbon part resulted in a better boat, the owners approved it. Weight saving remained front of mind throughout the build.

For example, Nilaya’s blade jib uses lashings to connect to its forestay instead of a headstay lock – thus saving 100 kilograms. Tapering the top of the mast generated a saving of 50 kilograms.

Rethinking the HVAC system saved 600 kilograms, reducing teak deck thickness from 15 or 16 millimetres down to nine millimetres saved 1,300 kilograms, and so it went. In the end, Royal Huisman delivered a hull 11 per cent lighter than its typical advanced Alustar construction, and by applying the methodology to systems and interior saved another four per cent in displacement.

FORWARD THINKING

ON BACKSTAYS

On large yachts with robust beams, easing the windward runner (which helps hold the mast in column) while taking up on what was the leeward runner, takes at least two people who must be in sync with the helmsman and the mainsheet trimmer. Nilaya’s innovative technology allows the crew to execute this important manoeuvre at the touch of a button.

Horizontally mounted hydraulic cylinders under the aft deck release and take up the running backstay cables led from underdeck winches by titanium fittings at precisely matched speeds.

The genius of the system is the precision-machined titanium “hook” that automatically snares and locks the load end of the windward sheet. On the new slack side of the system, a matching hook releases and drops gently into a little fitting that holds it snuggly atop its winch until it is needed again.

The owner’s requirements included a high-tech rig and very advanced gear to control the sails. He also inquired about the possibility of automating the running backstays and eliminating the huge deck winches controlling them. When a yacht is racing upwind, control of the running backstays during a tack is critical.

The weight-saving twin anchor system with fibreglass chain lockers and titanium arms that swing the anchor over the bow. Throughout the yacht’s build Royal Huisman took a hybrid approach to materials, mixing in carbon fibre with Alustar aluminium where it made sense. The entire 17.5m coachroof and guest cockpit area, the keel trunk and the recessed tender well on the foredeck are fully carbon fibre

The weight-saving twin anchor system with fibreglass chain lockers and titanium arms that swing the anchor over the bow. Throughout the yacht’s build Royal Huisman took a hybrid approach to materials, mixing in carbon fibre with Alustar aluminium where it made sense. The entire 17.5m coachroof and guest cockpit area, the keel trunk and the recessed tender well on the foredeck are fully carbon fibre

Unless the ballet goes precisely as choreographed, the tack is stalled, boat speed drops, and – in the worst case – the rig may be jeopardised. Considering the backstay loads on a sloop with a 62.5-metre mast, minimising risk to the carbon-fibre mast and the people beneath it deserved serious attention.

For this task, Rondal created its most advanced integrated sailing system, beginning with a first-of-its-kind backstay locking system. That system alone saved 1,200 kilograms and three cubic metres of space in the lazarette.

CARLO BORLENGHI

CARLO BORLENGHI

The foredeck features a partially recessed tender bay that can become a cosy cockpit at anchor with a hi-lo table and fitted cushions

“We set out to develop a totally different decisionmaking matrix for this project,” Rondal’s Bart van der Meer says. Usually, the naval architect specifies the sail area needed, the mast manufacturer creates the rig to hold it, the sailmaker supplies the sails and tells the builder where the deck hardware needs to go to trim them.

The builder then asks the winch manufacturer to develop gear sized to the loads and orders a hydraulic package to control it all. It gets assembled by the yard and then programmers create the logic software that makes things happen when crew push a button.

“The problem is that most programmers aren’t sailors and there is no communication with the crew about the boat’s operational profile. Most hydraulics suppliers size their package for maximum loads and then it’s up to the yard to make it fit somewhere, and the crew to figure it out,” van der Meer says.

CARLO BORLENGHIThe aft section of the cockpit has two innovative sun loungers that adjust up to 25-30 degrees to compensate for the yacht’s heel

CARLO BORLENGHIThe aft section of the cockpit has two innovative sun loungers that adjust up to 25-30 degrees to compensate for the yacht’s heel

Instead, for this project Rondal and Royal Huisman gave everyone a seat at the table during the development phase. Developing all the system needs in advance also meant that Nauta knew exactly the available interior volumes and shapes.

All decisions were immediately shared to all parties in the form of updated electronic plan files. Royal Huisman also made a full-scale deck mock-up that could be tilted to simulate heel for approving handhold placement and to allow the crew to check sight lines at all angles.

It enabled the owners’ team to decide, for instance, that they didn’t need a removable bimini and to refine the fixed bimini’s supports instead.

Considering the backstay loads, minimising risk to the carbonfibre mast and the people beneath it deserved serious attention

With Nauta and Reichel/Pugh having defined target weights for the interior, during construction every element was weighed going into the boat and all debris was weighed coming off.

To stay within the interior weight budget, Royal Huisman made extensive sound attenuation studies and developed sophisticated composite panels in cork, foam and honeycomb. It made cabin mock-ups demonstrating three levels of sound insulation and allowed the owners to choose the level of quiet they wanted to pursue.

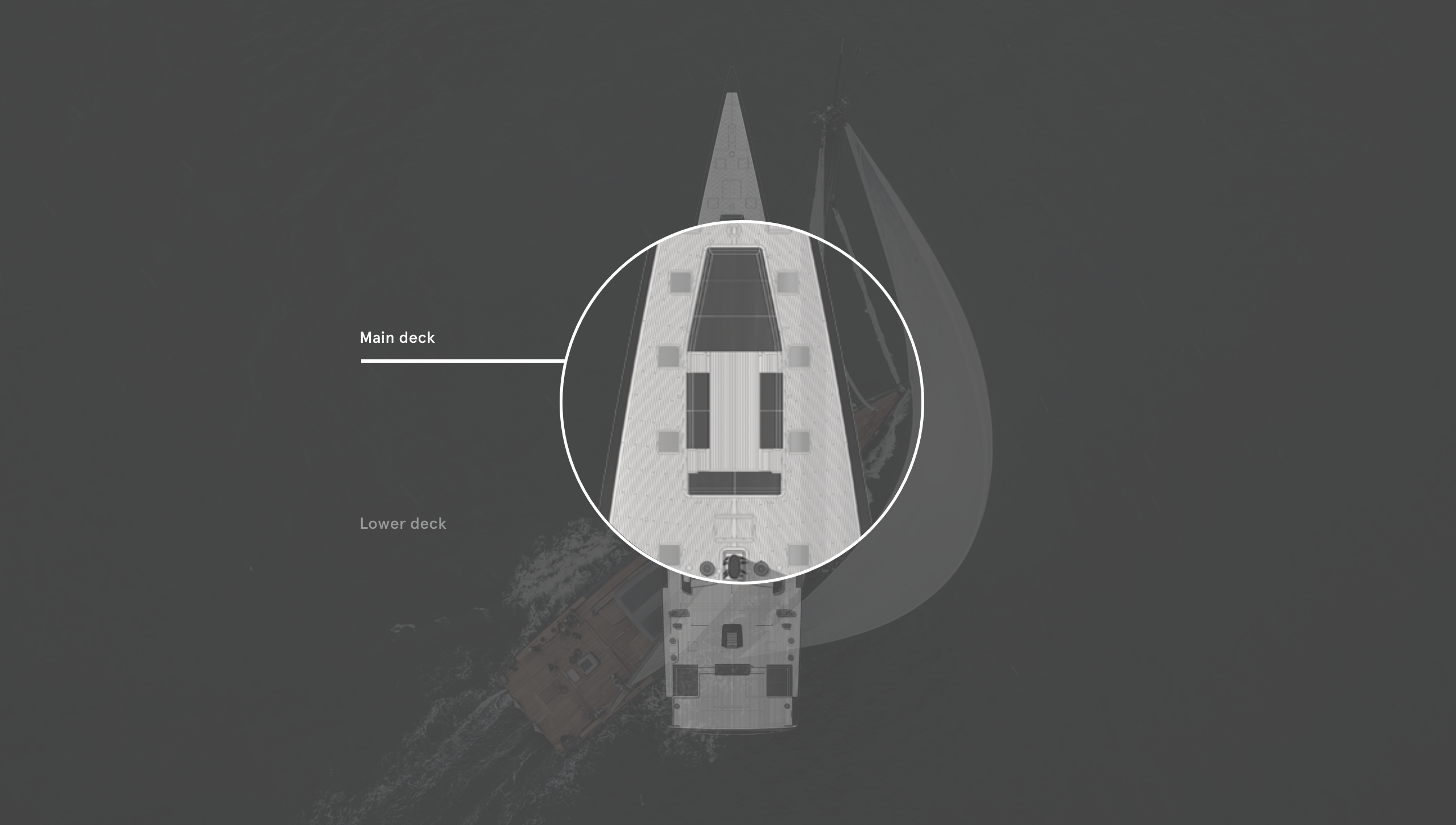

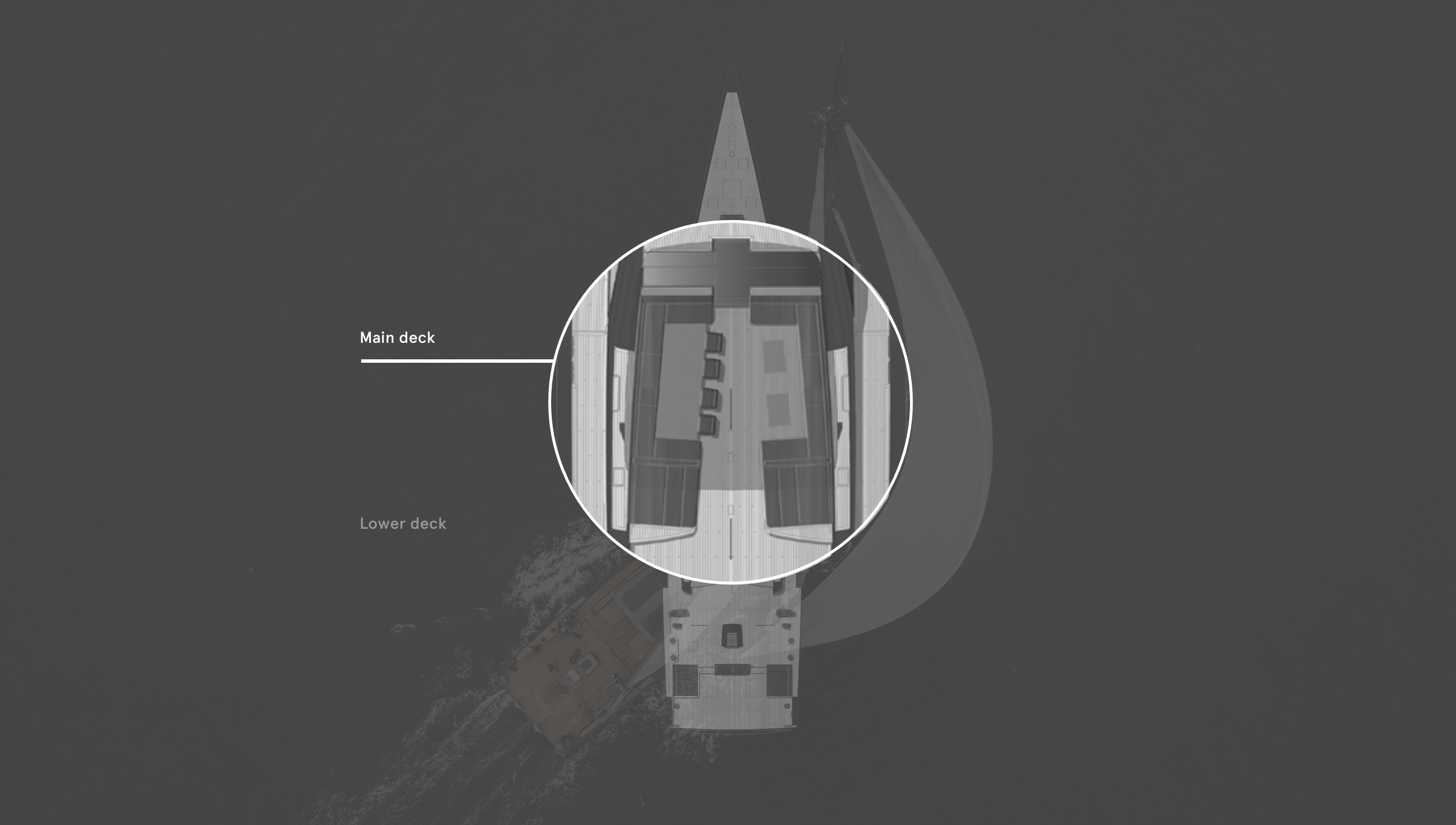

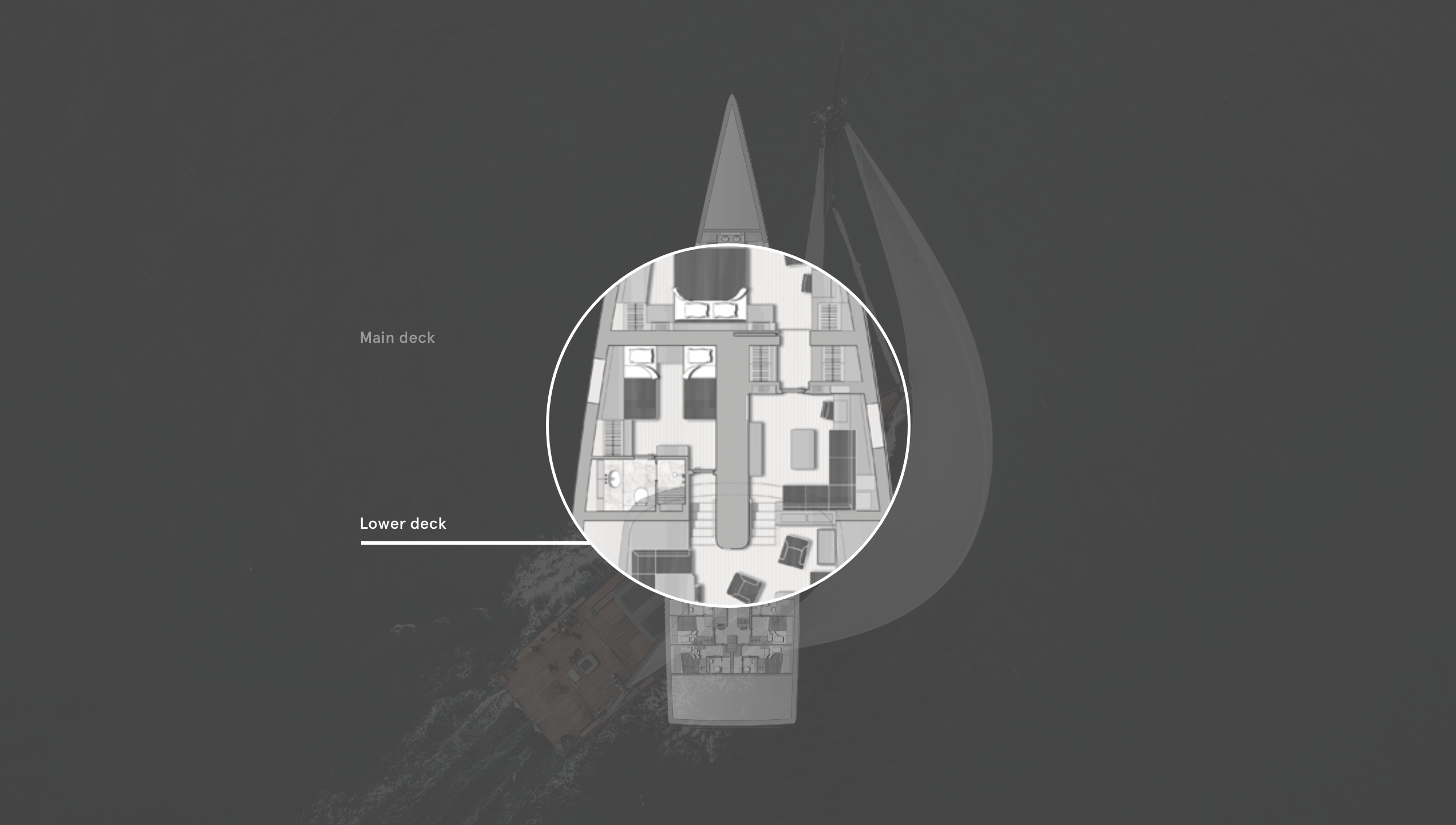

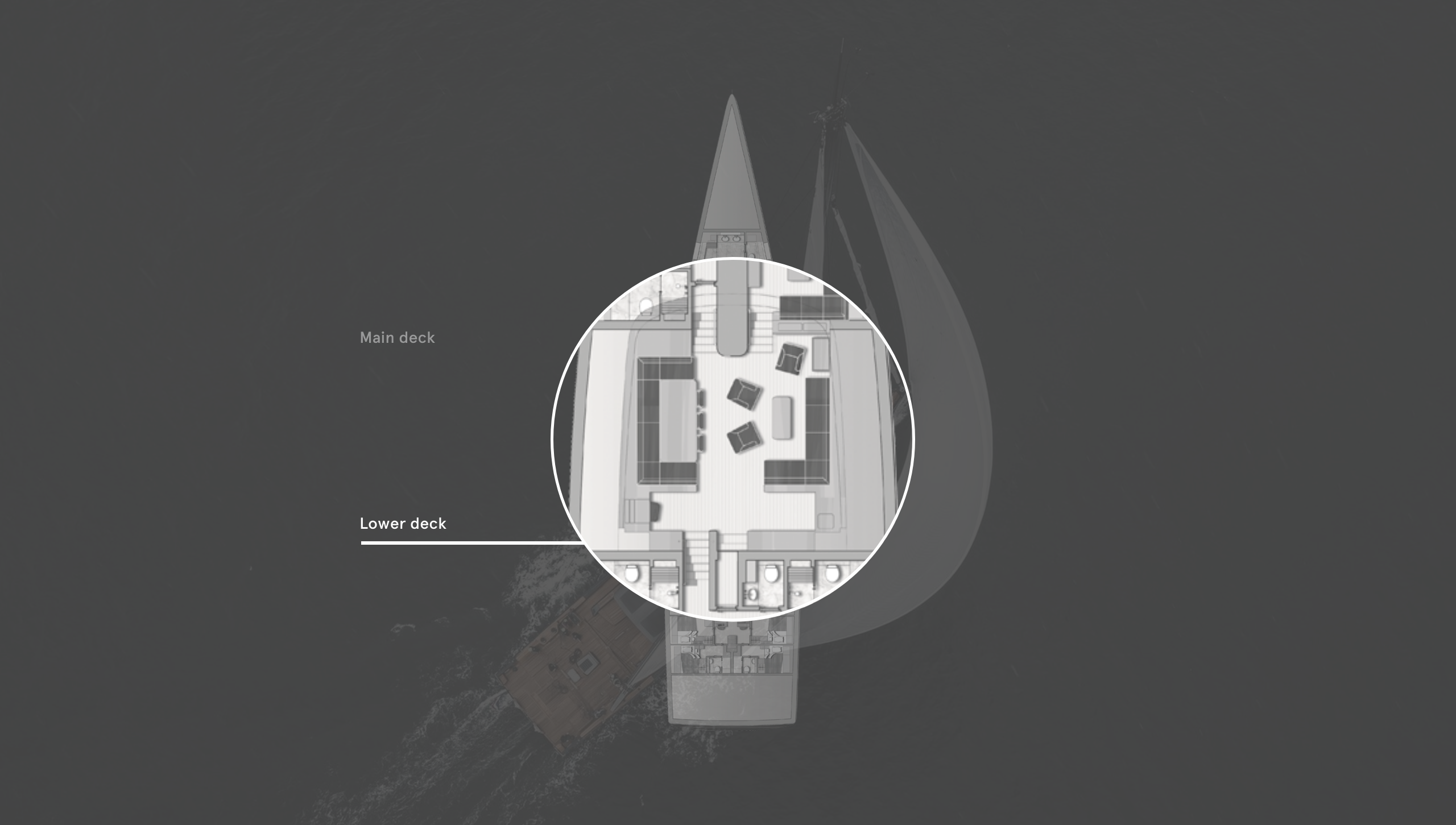

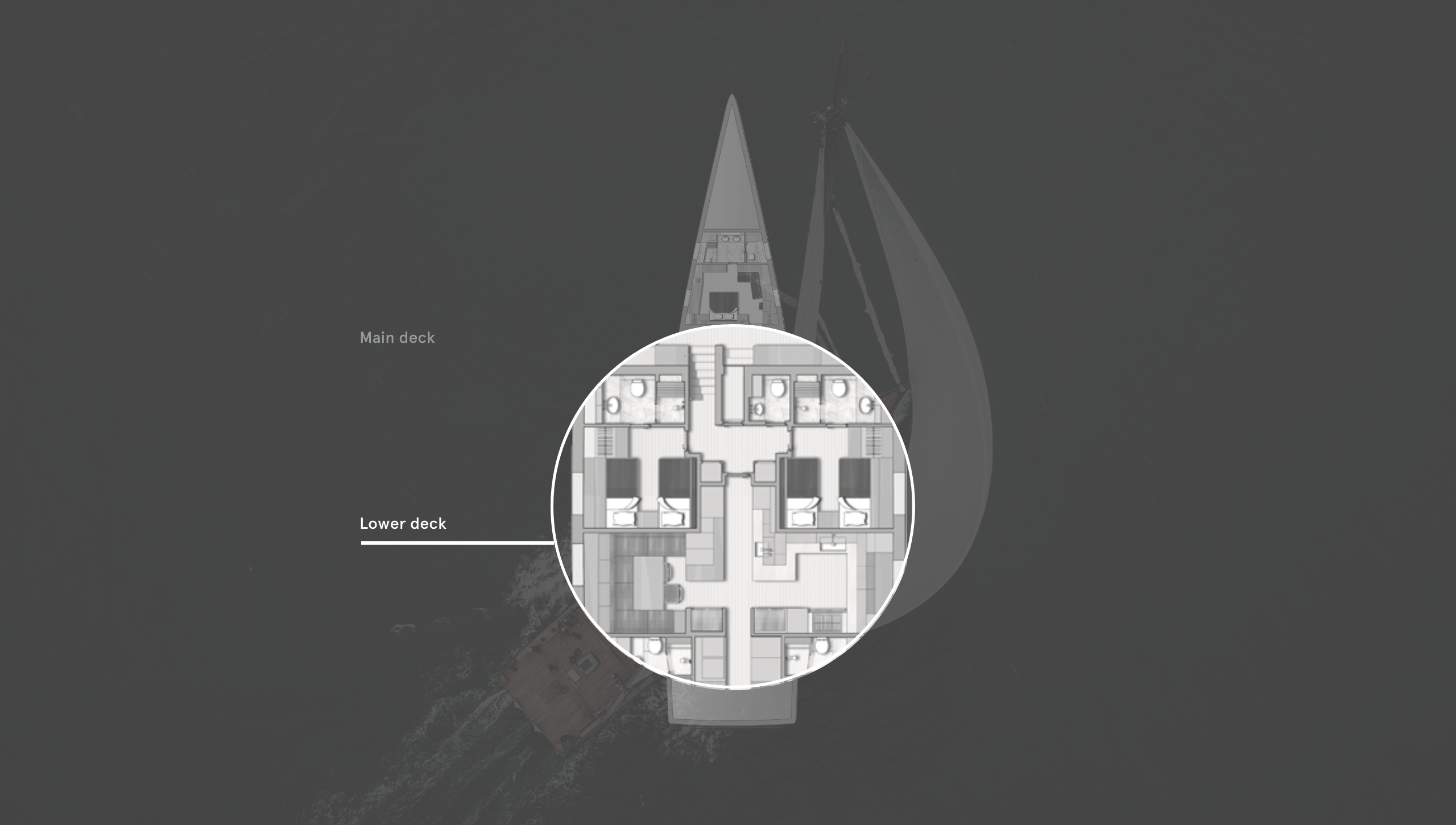

Nilaya, the largest sailing yacht yet by Nauta Design, features two guest cabins, a galley, a crew mess, chart table, an engineer’s station and four double crew cabins aft of the main saloon, plus a media lounge, VIP guest cabin and owners’ full-beam suite forward.

The owners’ designer, May Vervoordt, chose interior materials and, with Nauta, conceived a bright colour scheme against white lacquered walls and bronze-coloured fabric and leather overhead panels.

Mahogany furniture, flooring and ceiling frames give classic warmth and a homely quality, especially to the deck saloon. Nilaya, after all, means “peaceful abode” in Sanskrit.

Nauta’s experience with racing boats means that everything has its place – and in most cases, that is out of sight. Case in point, the deck saloon has an owners’ pantry where guests can avail themselves of coffee, drinks and snacks but they wouldn’t know it was there if it wasn’t pointed out.

For such a large yacht, the acceleration is exciting as she rapidly reaches high speeds

The full-width owner’s suite features a walk-in wardrobe, an office and sitting area and a king-sized bed. Large hull windows bathe the room in natural light. The cabin was a design challenge as it lies beneath the tender bay, but the overhead decorative treatment balances the tender bay’s central dip with higher side passages, giving an excellent perspective on the cabin’s impressive width.

The VIP, which can be arranged as twin berths or a double is to port, opposite a cosy TV lounge six steps lower than the deck saloon. The identical en suite guest cabins aft of the saloon convert into doubles and are both equipped with additional Pullmans, meaning up to eight guests can accompany the owners.

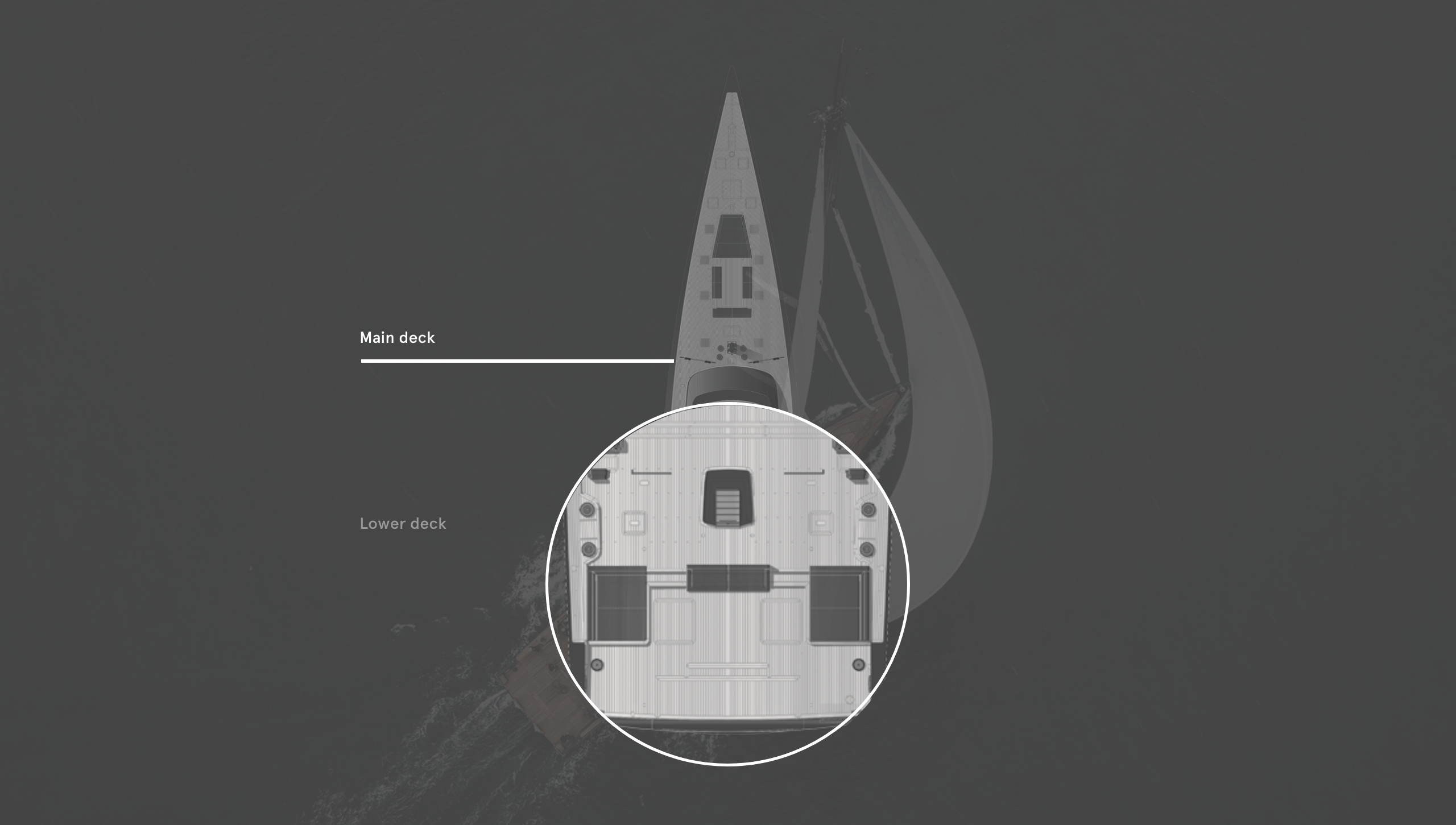

Mindful of the mission to cruise as well as race, Nauta Design developed three distinct outdoor guest areas in addition to the twin helm positions. The almost 10-metre-wide transom includes a hinged section that folds hydraulically to form a staircase that lifts out of the way for launching the crew tender.

On the aft section of the cockpit are two innovative sun loungers that adjust to compensate for the yacht’s heel. Removable railings from the transom to the guest cockpit guarantee that crew and guests are never more than two steps from a grabrail.

The guest cockpit, meanwhile, is shaded by a carbon composite hardtop with windows. Under this, the dining table can extend to host 14 guests. Finally, the foredeck features a partially recessed tender bay that can become a cosy cockpit at anchor with a hi-lo table and fitted cushions. An awning can be set up quickly and strung from carbon fibre poles that store in a deck hatch.

SAIL INNOVATION

Nilaya was the first yacht fitted with Doyle’s “structured luff” sails, which distribute the load a little differently through the material and sheet flat.

So flat, in fact, that Rondal had to develop radical new curved carbon-fibre spreaders that are both shorter and more aerodynamic than anything previously available.

Rondal also developed a new hybrid captive winch with a carbon-fibre drum that’s half the weight of other captive winches.

CREW NILAYAWith a mast height of 62.5m, Nilaya can sail into the Pacific, fitting under Panama’s Bridge of the Americas during low tide. Note the curved spreaders that Rondal developed to take advantage of the very narrow headsail sheeting angles possible with Doyle Sails structured luff sails

CREW NILAYAWith a mast height of 62.5m, Nilaya can sail into the Pacific, fitting under Panama’s Bridge of the Americas during low tide. Note the curved spreaders that Rondal developed to take advantage of the very narrow headsail sheeting angles possible with Doyle Sails structured luff sails

Nilaya was the first yacht fitted with Doyle’s “structured luff” sails, which distribute the load a little differently through the material and sheet flat.

So flat, in fact, that Rondal had to develop radical new curved carbon-fibre spreaders that are both shorter and more aerodynamic than anything previously available. Rondal also developed a new hybrid captive winch with a carbon-fibre drum that’s half the weight of other captive winches.

CREW NILAYAWith a mast height of 62.5m, Nilaya can sail into the Pacific, fitting under Panama’s Bridge of the Americas during low tide. Note the curved spreaders that Rondal developed to take advantage of the very narrow headsail sheeting angles possible with Doyle Sails structured luff sails

CREW NILAYAWith a mast height of 62.5m, Nilaya can sail into the Pacific, fitting under Panama’s Bridge of the Americas during low tide. Note the curved spreaders that Rondal developed to take advantage of the very narrow headsail sheeting angles possible with Doyle Sails structured luff sails

A lighter yacht needs less power for motoring, in this case, one fewer generator and gearbox – a factor that leaves more space for interior accommodation and which saved another 2,000 kilograms. The single propeller can be powered directly from the engine and/or electrically, either from batteries or a generator, which eliminates the need for a third get-home engine.

The team got to test the results extensively. The owner, captain Romke Loopik and pro race team captain Bouwe Bekking were on board for Nilaya’s first transatlantic in November. It was a fast 10 days with instruments recording a top speed of 20-plus knots, and the owners’ verdict was “very comfortable and fast”.

“For such a large yacht, the acceleration is exciting as she rapidly reaches high speeds,” Ingram says. “Twin rudders and the light, positive steering give superb manoeuvrability and she seems to be reaching all her targets with ease. Rondal’s sailing systems enable fingertip control of the massive loads involved.”

RONDAL SJB

RONDAL SJB

At the 2024 St Barth’s Bucket in March, Nilaya proved the point, winning on the third day of racing and finishing third overall in her class in her first ever Bucket regatta.

Royal Huisman CEO Jan Timmerman says the innovations on Nilaya can be applied to future sailing yacht builds. “The owners deserve congratulations for pushing everyone to achieve just a little bit more and for encouraging innovation at every step. Nilaya will be the world’s lightest sailing superyacht for her length. She rewrites the script for aluminium highperformance yachts.”

She may be lightweight, but there is no doubt that Nilaya is a technological heavy hitter.

First published in the June 2024 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.

The tender bay can be covered with a carbon composite covering to become a flush deck

The shaded guest cockpit is lined with sofas around the dining and coffee tables

A 4m crew tender stows behind the transom

The VIP cabin can be arranged as twins or a double

The deck saloon enjoys near- all-round views

A Pullman berth in each aft suite means Nilaya can take up to 10 guests

LOA 47m | Gross tonnage |

LWL 45m | Engine |

Beam 10m | Generators |

Draught (keel up/down) 4.5m/6.9m | Rig |

Sails | Sail area |

Fuel capacity | Owners/guests 8-10 |

Freshwater capacity | Crew |

Tenders | Construction |

Classification | Naval architecture |

Exterior and interior design | Builder/year |

Interior decor | +31 (0)527 24 3131 yachts@royalhuisman.com royalhuisman.com |