OFF-GRID ADVENTURE

What it takes to cruise where few yachts ever go

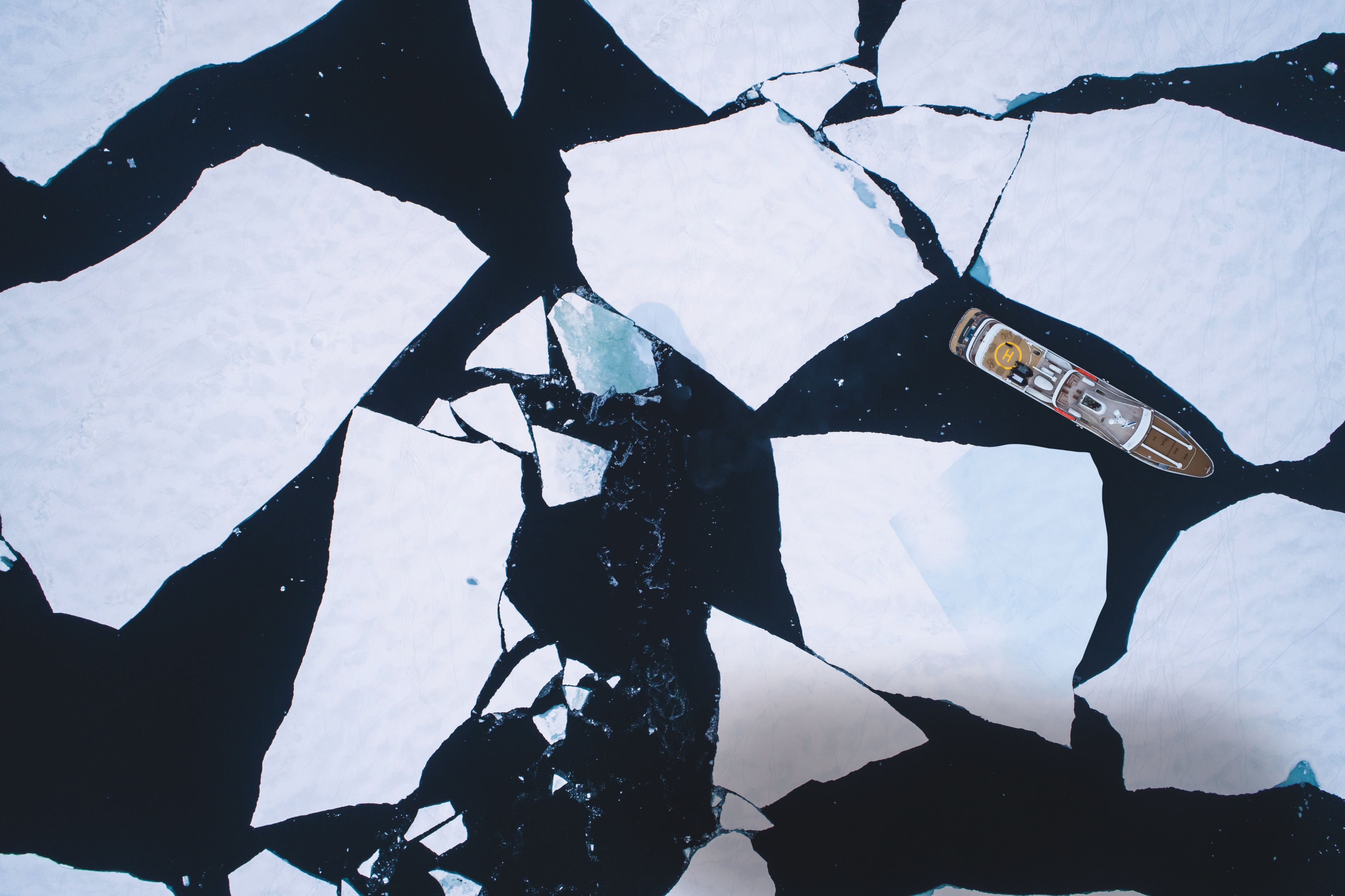

Sailing to remote destinations offers bucket-list exploits, vanishingly rare sights and experiences few will ever share, but it brings its challenges, too. Elaine Bunting talks to a circumnavigator captain about the preparation required to ensure you're ready for anything

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

At the southernmost tip of Patagonia is a stretch of the Beagle Channel nicknamed Glacier Alley. The 240-kilometre passage is serrated by fjords cut by five tidewater glaciers that flow from the huge Darwin ice field. Captain Gerhard Veldsman recalls taking Aquijo, at 85.9-metre the largest sailing ketch in the world, gingerly into them as one of the most memorable experiences of a decade of two circumnavigations.

“We had the boss and his family on board for a month. We went right up to all the glaciers and the sights were amazing,” Veldsman says. He describes immense ice cliffs, an evening barbecuing on a wild, isolated beach and making a luge from iceberg ice and filling it with vodka. “It was one of those surreal moments,” he says, “with silence all around, a mountain of ice nearby and the family laughing around the fire.”

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS A frequent visitor to Antarctica, Legend is a 77-metre explorer with an ice-classed hull

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS A frequent visitor to Antarctica, Legend is a 77-metre explorer with an ice-classed hull

Aquijo was always destined to sail to remote regions and go the long way round the world as her 90-metre masts are too tall for the height restrictions of the Panama and Suez Canals. “We have to go via the extremities of the planet to get around the world,” explains Veldsman.

Since her launch in 2016, she has rounded the tip of South America and been through the Northwest Passage, transiting some of the world’s most demanding and difficult waters. Her guests have seen volcanoes, polar bears and pristine reefs, and been to mountain communities with ancient tribal cultures.

Sailing to these places can be demanding in a boat as large and complex as Aquijo. You need to take along experts for pilotage expertise and their understanding of cultural nuances.

TYLER WILKINSON: EYOS EXPEDITIONS Doug Stoup is a polar ski guide for EYOS

TYLER WILKINSON: EYOS EXPEDITIONS Doug Stoup is a polar ski guide for EYOS

GOING BEYOND THE KNOWN

Eyos Expeditions was set up in 2008 to help superyacht owners and their crews prepare for these special places, to take them “beyond the known”.

“Yachts are such a great platform with their small, intimate sizes. Our idea was to support crews to break out of their comfort zone, as we saw yachts going to places and missing out on some of the best experiences because they didn’t know who to reach out to. We make recommendations on how a yacht should be prepared, develop an itinerary and take care of permits,” says CEO and former captain Ben Lyons.

In the early days there was more of a standard expedition playbook, “but now we are able to put together programmes that are so much more complex and ambitious. For example, we took a yacht to the Ross Sea recently and it was the furthest south a yacht had ever been in history – nobody ever thought you could do it,” Lyons says.

“We routinely help with programmes involving several vessels, including support yachts and helicopters, and people can be off heli-skiing, hiking, kayaking or doing scientific expeditions on the ice cap.”

For all high-latitude voyages, EYOS begins with “what we call a pre-polar meeting, where we send a couple of team members to meet with captain, chief engineer and chief stew and run through a comprehensive checklist and any questions they may have”, Lyons explains. “That could be anything from garbage disposal to access points where a polar bear could come on board.

COURTESY OF AQUIJO Gerhard Veldsman has skippered Aquijo through weeks of cruising without seeing another boat or human

COURTESY OF AQUIJO Gerhard Veldsman has skippered Aquijo through weeks of cruising without seeing another boat or human

“On top of that, we have extensive standard operating procedures for things like small boat operations and wildlife encounters – wildlife viewing is a huge one from a safety perspective and also ensuring responsible behaviour so we view the animals acting naturally. This all forms part of our submission for permit applications.”

The Antarctic and Arctic tourism consortiums IAATO and AECO, of which EYOS is an operating member, “lay out all sorts of guidelines, even down to site specific locations, like you can land at Neko Harbour [Antarctic Peninsula] at this spot but you can’t go to that spot because there is a colony of birds or there were crevasses there earlier. So we even have that level of playbook that we are working to,” Lyons says.

EYOS co-founder Rob McCallum adds that places like Neko Harbour, a real staple for tourist vessels, is booked most days of summer. “It is an awesome spot but it is also one of the most visited commercial sites. The flexibility of a private expedition on a yacht gives us the freedom to find better spots that are off the tourist trail.”

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS EYOS expedition guide Richard White

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS EYOS expedition guide Richard White

On Aquijo’s first voyage via Cape Horn and Patagonia, the yacht had EYOS consultant Skip Novak with them. Novak has operated his own expedition yachts in Antarctica for more than three decades. He knows the area intimately and has a extensive knowledge of the weather, ice behaviour and the flora, birds and marine life.

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

A local pilot is also mandatory in Chilean waters. Veldsman emphasises how crucial it is to find one accustomed to superyachts: “Guides are critical in places like this, but you need a pilot that is used to big boats and accommodating guests,” he says. “We had a guy called Marcel, and he was great, knew the area very well and was proud of showing us his country.”

Yachts must be well prepared and self-sufficient, and their crews cautious. “We travelled for two weeks from Ushuaia to [the southern Chile town] Chacabuco without seeing another living soul. You are isolated and even if boats have helicopters they are not allow to fly unless they have to. You have to be able to survive,” Veldsman says.

REEVE JOLIFFE/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

REEVE JOLIFFE/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

The weather can be unpredictable, and winds can move ice around quickly and trap or embay a yacht. “The wind can go from zero to storm force in a few seconds, and it happened a few times,” he says.

“You must be ready for that. If you anchor in front of glaciers you won’t know how deep it is, so you send tenders out ahead of you. But if the wind swings and the ice breaks up off the glacier and you need to move, you have to be careful not to get them in your thrusters. Or if your chain were to get trapped underneath an iceberg and you couldn’t get the anchor up, you’d have to let it go.

“All of these things can happen to you – that’s what it is like down there. So you prep the crew that it is going to be hard work, but it is very exciting for everybody as it’s all new, and if you have a good crew it is fantastic.”

“The wind can go from zero to storm force in a few seconds. You must be ready for that”

The second circumnavigation took Aquijo through the Northwest Passage, a two-and-a-half-month odyssey that began in Boston and finished in Nome, Alaska. The route took them via Greenland to the north of Canada, and the preparation was rigorous – “even more involved than Patagonia”, comments Veldsman.

Complex permissions were required and additional insurance and certification. Daily passage plans had to be filed en route. “All our officers did ice navigation courses,” says Veldsman. “The Coast Guard is very specific. They don’t want you to get trapped in the ice as they have to come and get you.”

“Expedition cruising in challenging ice conditions is dynamic, intense and rewarding,” says McCallum. “It requires hard-won expertise, satellite imagery, great shore support and patience. Conditions change daily, so you need an alternative plan and a flexible mindset.”

When you see the ice, however, this all becomes worthwhile. Disko Bay in Greenland was one of the high points of Aquijo’s trip, full of towering, white and turquoise icebergs, “some as big as two or three rugby pitches”, Veldsman recalls. “You literally see them marching; it is amazing, but they are also very unstable and can turn around next to you and you quickly want to get out of their way.”

An ice pilot is mandatory for insurance for this region. Initially, Veldsman was sceptical. “I thought it was a waste of money,” he admits, “but as soon as we hit Greenland, we saw icebergs very quickly, and it was quite daunting. The pilots do add value if they are good. They will talk you through getting a path through the ice as they have an eye for how it moves with the tides and wind.”

One of the most remote stops in the Northwest Passage transit was Cambridge Bay in northernmost Canada, which is ice-free for only 10 days a year. Aquijo had a contingency plan in place for topping up fuel here by taking two one-cubic metre containers with them, craning them out onto a tender and going to a beach where a fuel truck from a local community could drive to and fill them up. That worked perfectly, but the crew also had to be mindful not to deplete these tiny communities’ limited resources.

Aquijo took a specialist expedition doctor who had worked extensively with polar explorer Ranulph Fiennes. Although she was never needed, she was on board “just in case”.

External expertise was invaluable in many other places round the world. In Papua New Guinea (PNG), Aquijo had the help of local expert Angela Pennefather, an EYOS expedition leader who works in the yacht support industry in Australia but grew up in PNG. “She is the expert in Melanesia. If you want to get the best out of it, you need to take a good local guide with you,” says Veldsman.

Pennefather took quick action during an emergency when a crew member developed decompression sickness after a routine dive. She arranged for a specialist air ambulance capable of flying at low altitude, vital for keeping air pressure as close as possible to sea level, to take the crew member to Australia, where they were treated for two weeks before being discharged.

“There isn’t much availability of doctors on small islands so you need to insure yourself properly for adventure travel. It is like a life raft; the day you need it you will be grateful for it,” Veldsman emphasises.

Even close to the beaten track you can find rare wildlife, secluded communities and deserted beaches

Pennefather helped Aquijo’s crew in many other ways. “I co-ordinate community engagement, whether it’s arranging educational workshops, health support or repairs,” she says. “My job is to transform an expedition from a passive journey into an experience with real social impact. It’s the difference between being a tourist and becoming part of a shared human story,” she explains.

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

“Papua New Guinea is one of the last true frontiers where ancient tribal traditions still exist and you have this incredible spirit within the people,” she adds. “There’s something really moving about seeing one of the world’s wealthiest individuals sitting cross-legged, sharing a coconut with a village child. It reminds people what really matters and it reconnects them with a shared humanity – that is what makes it unforgettable.”

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

COURTESY OF AQUIJO

“As a nation of 850 language groups, PNG is an anthropological mecca,” Pennefather continues. “Cultural opportunities abound. In the Louisiade archipelago you can sail a traditional sailau ocean-going canoe. Constructed of nothing but natural materials, these simple craft voyage across vast tracts of the ocean, powered by the wind and their typically joyful crew of four.

In Melanesia, you can find yourself on islands

that have not had a visitor in years

“New Ireland is home to the ‘shark callers of Kontu’, where men in tiny dug-out canoes catch sharks by hand using nothing but a noose and a hard-carved propeller, an ancient art unique to this place and this culture,” Pennefather concludes.

“Every island has a different culture – different rituals, dances and songs that carry traditions through the millennia. These are shared willingly, with the entire village turning out to perform for us in New Hanover, an authentic cultural event that brings the village together to give the warmest of welcomes.”

Beyond the traditional trade wind routes are a multitude of coastlines few yachts ever visit. In Melanesia, you can find yourself on islands that have not had a visitor in years, and hundreds of islands that are completely uninhabited.

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

MOSAIC STUDIOS/EYOS EXPEDITIONS

Even close to the beaten track you can spot rare wildlife and marine life, secluded communities and deserted beaches. “The diving in French Polynesia was amazing, the outlying islands of Papua New Guinea and all of Melanesia were all highlights, but other places stood out, too,” says Veldsman.

“In Tasmania, there were beautiful beaches with kangaroos and wombats and nothing else on them. Hobart had the best whisky in the world, and wineries and museums. We saw places that were very different to the remote locations. There were so many surprises.”

First published in the September 2025 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.