SPEED OF SOUND

The untold story of the Aga Khan's revolutionary boats

James Evans explores the Aga Khan’s lifelong obsession with speed: the yachts it created, the records it broke and the technical advances it generated - especially in his parallel quest for silence

POOL BENALI LE CORRE - GAMMA ROPHO - GETTY IMAGES

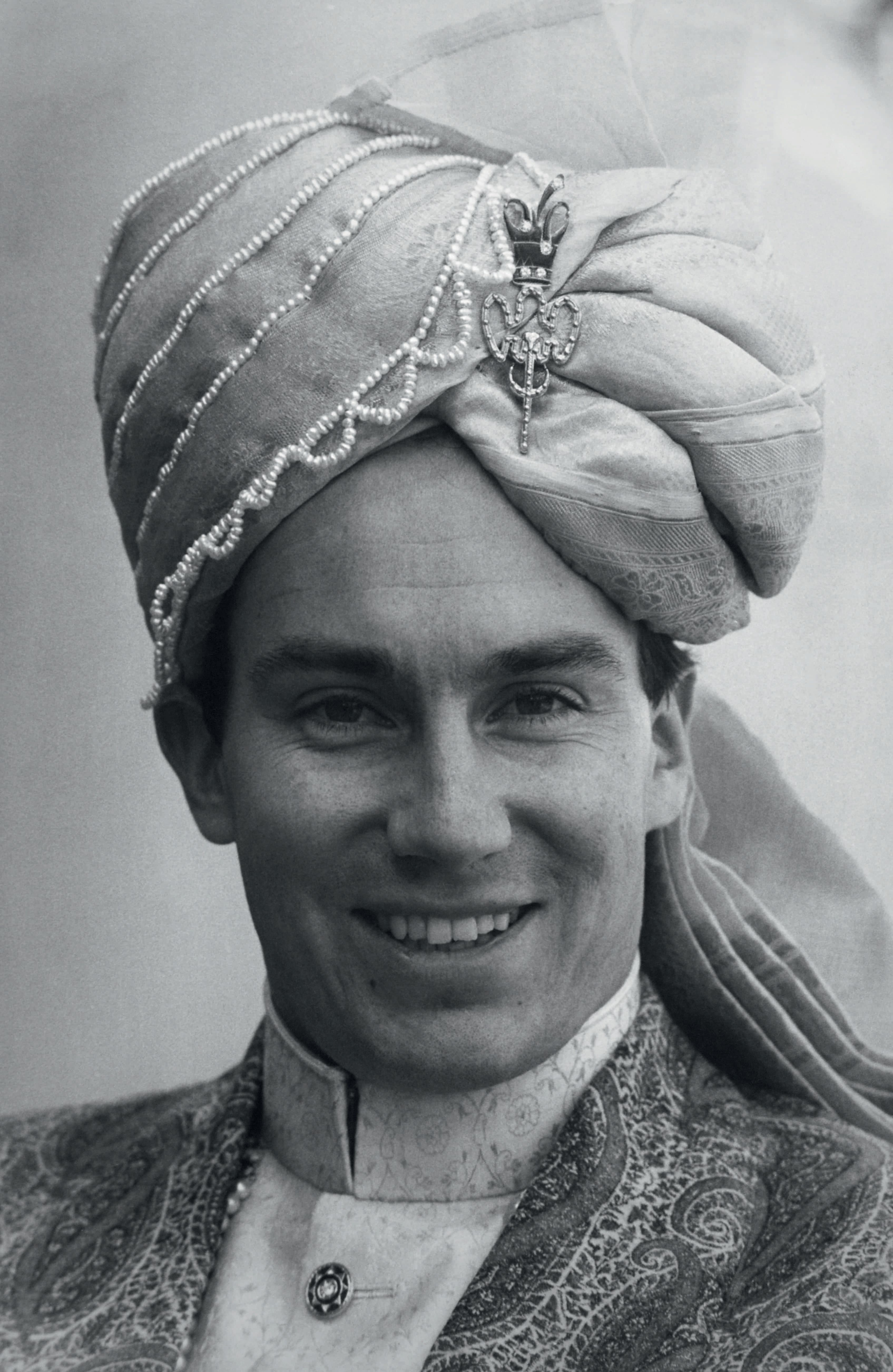

Whatever the means of travel, the late Aga Khan – His Highness Karim al-Hussaini – yearned to go fast. Racehorses, sports cars, yachts: he owned and loved them all. A Maserati 5000 GT made for him in the 1950s was, for a time, the fastest road car in the world. It was certainly an appropriate form of transport.

The desire for speed was with him from an early age. Raised in Switzerland, he trained with the Austrian ski team, then represented Iran at the 1964 Winter Olympics. His middling finish he deemed “respectable if not glorious”. For someone venerated as a spiritual leader to Nizari Isma’ili Muslims, he rather liked being middle-of-the-road and nondescript, even if that road was full of elite sportspeople.

GERARD GERY - PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGESRaised in Switzerland, he was a competitive skier

GERARD GERY - PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGESRaised in Switzerland, he was a competitive skier

Looking back now, after his death in February this year, Andrew Glossop – from 2009 his chief engineer and then manager of his whole fleet of boats – remembers the unadulterated passion that those boats inspired in him.

He bridles at the notion that his “boss”, as he calls him, was any kind of playboy – a lazy presumption about “boys with toys”. Quite the contrary, he insists. “He was one of the most amazing people that I have ever met. He worked every day of his life,” Glossop says, “tirelessly.”

SLIM AARONS - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESThe Aga Khan IV at the bow of his yacht on the Costa Smeralda in Sardinia in 1967

SLIM AARONS - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESThe Aga Khan IV at the bow of his yacht on the Costa Smeralda in Sardinia in 1967

He had profound patience – and knew that sometimes you had to go slow in order to go fast. One of his most famous boats, Alamshar – currently for sale with YPI – was a very difficult and protracted build. It required commitment, staying power and the willingness to conquer numerous frustrations.

But he always enjoyed a project just as much as he did the product. And throughout the process he remained closely involved. “I do not know another person who would have finished that project,” Glossop says.

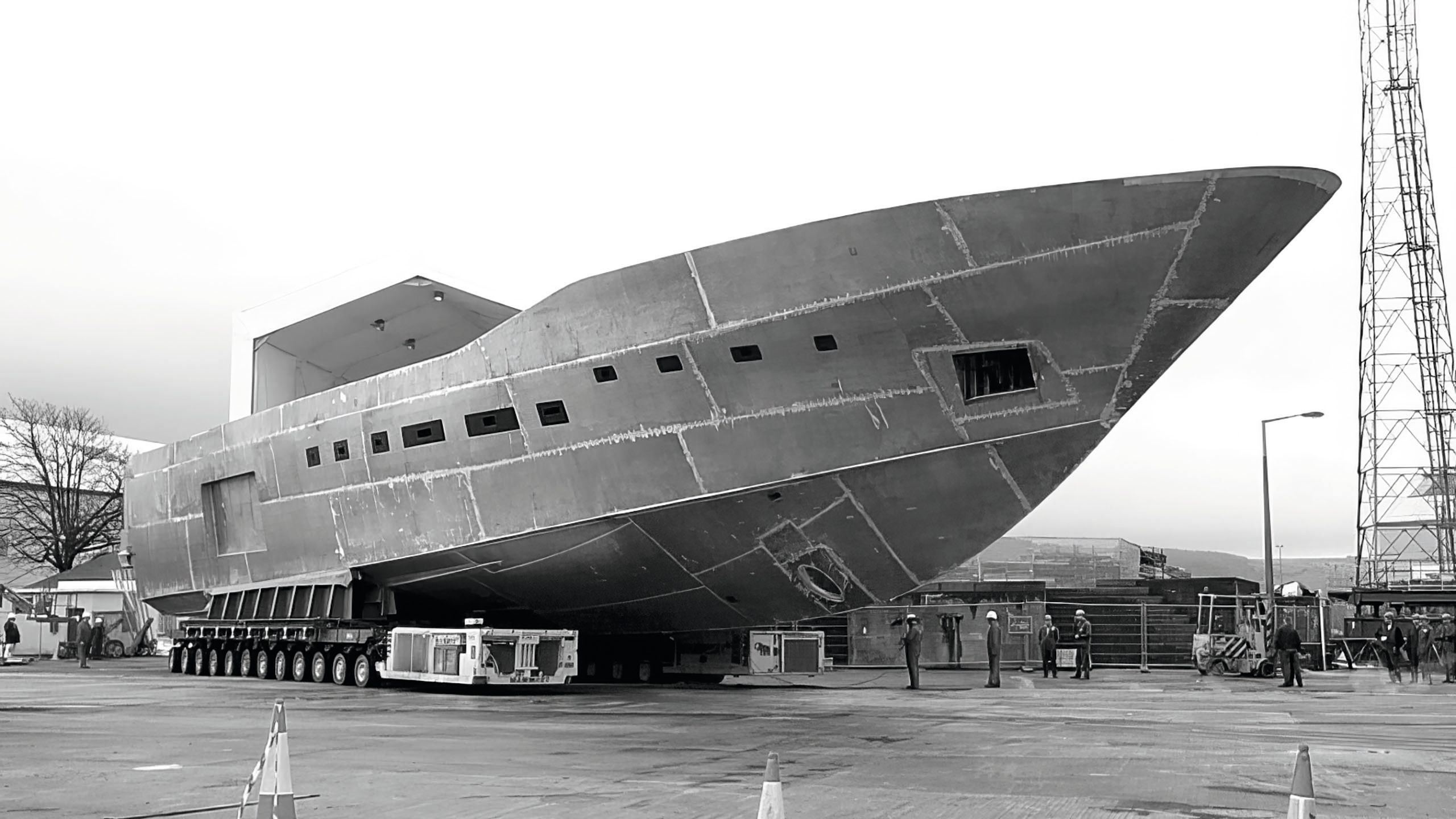

COURTESY OF DLBAAlamshar in build at Devonport

COURTESY OF DLBAAlamshar in build at Devonport

As with any craft or vehicle meant to travel fast, the critical thing is weight, says Jeff Bowles, who was involved in the construction of Alamshar and worked on the design and build of the Aga Khan’s other yachts. With any problem that arises on this sort of build, he notes, “you can always throw weight at it.” Add a piece here. Thicken a panel there. “But of course, weight robs you of speed.” This is a fundamental truth of yacht design.

So, for instance, the material from which the body of the vessel was built was critically important. Strength needed to be offset against weight. And so Alamshar was built using the largest piece of moulded, composite material ever used – anywhere. In the process the Aga Khan pushed the boundaries in a manner that came to influence multiple industries, not simply those we would consider maritime.

He knew that sometimes you had to go slow in order to go fast

There were many other hurdles, the surmounting of which took time and patience “What a special and innovative boat Alamshar was,” Bowles now recalls, talking with great fondness about her remarkable COGAG (combined gas turbine and gas turbine) propulsion system. No other remotely similar boat had had the like when she was built, he says, and few have done so since.

It was a propulsion system that had previously been used only for naval vessels, attaching large and small (“father and son”) turbines to the drive shafts in order to permit both high-speed operation (with everything running) as well as more fuel-efficient cruising, when only the smaller turbine – the “son” – was operational.

REPORTERS ASSOCIES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

REPORTERS ASSOCIES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Courtesy of AKDN

Courtesy of AKDN

Courtesy of AKDN

Courtesy of AKDN

The Aga Khan pictured in 1967; with US President Kennedy in 1961 and with Kenyan President Kenyatta in 1966

Making a 50-metre boat travel at 65 knots is, Bowles emphasises, not easy, and it requires a huge amount of power: 50,000 horsepower in this case. The engine room becomes phenomenally hot, and then this heat has to be removed if the vessel is not going to suffer in other respects.

One consequence, as Bowles remembers, was that a stern door had to be specially ordered from the aerospace industry, with a ceramic coating that was sufficiently resistant to the extreme temperatures. There was a reason why this hadn’t been done before.

ALBERTO MAISTO - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOOn board yacht Shergar

ALBERTO MAISTO - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOOn board yacht Shergar

One thing that is critically important to remember is boats, for the Aga Khan, always had to fulfil a dual function: they had to be fast, but they also had to be comfortable and quiet. They had to be places in which he could think, and talk and work. Always, therefore, he was motivated by the desire to keep both vibrations and noise levels as low as was consistent with high speed.

Life on the ocean offered him rare moments of pleasure, peace and tranquillity

On many of his vessels therefore – on his twin yachts Zarkava and Valyra for instance – he used technology drawn from helicopter design (where noise reduction is enormously important). He copied the idea of making the internal compartment almost a cocoon.

Instead of being supported from the bottom, as is the case with most boat interiors, this pod was in essence hung from close to the sheer line – and so not attached to (and indeed insulated from) the thumping noise made by waves striking the hull at speed. The fact that the mount on which the cocoon was hung was elastic, further mitigated the shock and the noise.

One thing that is critically important to remember is boats, for the Aga Khan, always had to fulfil a dual function: they had to be fast, but they also had to be comfortable and quiet. They had to be places in which he could think, and talk and work. Always, therefore, he was motivated by the desire to keep both vibrations and noise levels as low as was consistent with high speed.

On many of his vessels therefore – on his twin yachts Zarkava and Valyra for instance – he used technology drawn from helicopter design (where noise reduction is enormously important). He copied the idea of making the internal compartment almost a cocoon.

Instead of being supported from the bottom, as is the case with most boat interiors, this pod was in essence hung from close to the sheer line – and so not attached to (and indeed insulated from) the thumping noise made by waves striking the hull at speed. The fact that the mount on which the cocoon was hung was elastic, further mitigated the shock and the noise.

IMAGE CREDITS

IMAGE CREDITS

IMAGE CREDITS

IMAGE CREDITS

IMAGE CREDITS

IMAGE CREDITS

At the opening ceremony of The Ismaili Centre in Dubai in March 2008; addressing members of the Ismaili community in the Darvaz region, Tajikistan in 1998; at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan in 1996 (Credit: Courtesy of AKDN)

Above and below the waterline, inefficient shapes disturb flow, which creates both drag and acoustic noise. When you want both to move at high speed, and when noise levels are a concern, aerodynamic engineering is just as important as the hydrodynamics.

THURSTON HOPKINS PICTURE POST - HULTON ARCHVE - GETTY IMAGESBattista Pininfarina with son Sergio in 1956

THURSTON HOPKINS PICTURE POST - HULTON ARCHVE - GETTY IMAGESBattista Pininfarina with son Sergio in 1956

For Alamshar, everything below the waterline was by Donald Blount, renowned for his high-performance hydrodynamic shapes and naval architecture. For streamlining above the waterline, the aerodynamics expert that the Aga Khan consulted was Pininfarina, the legendary car design firm known in particular for its work with Ferrari. With design finalised, Alamshar was built at Devonport’s shipyard in Plymouth.

Life on the ocean offered him rare moments of pleasure, peace and tranquillity

POOL BENALI_LE CORRE - GAMMA RAPHO VIA GETTY IMAGESRecord-breaking yacht Destriero

POOL BENALI_LE CORRE - GAMMA RAPHO VIA GETTY IMAGESRecord-breaking yacht Destriero

Blount’s talents were well known to the Aga Khan, as they had worked together in the early 1990s when they collaborated on his boat Destriero – a 68-metre built to break the Atlantic speed crossing record.

Unusually perhaps for this owner, Destriero did not prioritise comfort or ease of conversation because her concern was solely to win the Columbus Atlantic Trophy for the fastest two-way crossing of the ocean.

He successfully achieved this goal in 1992, on a 52,000-horsepower gas turbine-powered boat that was capable of maintaining close to 70 knots, even in seas with waves two-and-a-half metres high. He refuelled in New York, came back across the Atlantic and still holds the record.

REMI BENALI - GAMMA RAPHO VIA GETTY IMAGESWith Gianni Agnelli at the helm of Destriero in 1991

REMI BENALI - GAMMA RAPHO VIA GETTY IMAGESWith Gianni Agnelli at the helm of Destriero in 1991

Subsequently the Aga Khan always harboured dreams of turning Destriero into a fast yacht for other purposes – and making her comfortable. But the truth is that, while his passion for speed never changed, as he became older, some dreams became harder for him to realise.

This, as Glossop admits, was one project too far. She was dry docked in northern Germany, stripped of her turbines and soon after her 30th anniversary she was broken up.

On account of his great interest in horse racing as well as in yachts, many of the Aga Khan’s boats were named after well-known horses that he had owned: Alamshar, Zarkava, Valyra. He had owned the derby winner Shergar – infamously kidnapped of course – and owned a yacht of the same name.

He commissioned and owned six or seven substantial yachts in the course of his life. Glossop is unsure about calling any boat his favourite – parents would rarely admit to having a favourite child. But when pushed it is Alamshar and Shergar on which he settles.

DAVID CARINS - DAILY EXPRESS - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESWith horse Zeddaan in 1973

DAVID CARINS - DAILY EXPRESS - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESWith horse Zeddaan in 1973

Shergar was built in 1983. The famous horse after which she was named was kidnapped from the Aga Khan’s stables in Ireland on 8 February that year so the memories were very fresh. The horse was extremely successful, most of his notable victories having taken place in 1981.

After his retirement from racing he was put out to stud – from where he was stolen. There was consequently a huge amount of emotion and pride involved in the boat of the same name.

AJAX NEWS & FEATURES SERVICE - JONATHAN EASTLAND - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOYacht Shergar

AJAX NEWS & FEATURES SERVICE - JONATHAN EASTLAND - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOYacht Shergar

He had her built originally at Lürssen, in northern Germany, then undertook a major refit in 2016 with the aim of giving her another three decades of life – so that his family could continue to enjoy her as he had done.

It would have cost a similar amount for him to have built a new boat, but it would have lacked the emotional appeal. As ever with his boats, the extent to which they mattered to him was about much more than their financial value.

His was a very public life, lived in the public gaze. And so life on the ocean offered him rare moments of pleasure, peace and tranquillity. It was a place where he could pursue his passion for speed away from public attention, with no one to judge or to question.

And the small advancements that he made were significant steps for the industry as a whole. This feels like an accolade with which he might be comfortable: not a solitary, standout figure but part of a great and honourable continuum.

First published in the December 2025 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.