ZERO MISSION

World exclusive – the inside story of the world's first zero-emission superyacht

Caroline White reveals Project Zero, the mission to build a luxurious 69-metre sailing yacht that doesn’t use a drop of fossil fuel – and the extraordinary discoveries they’re making along the way

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

On a sunny Saturday morning in July 2019, Marnix Hoekstra arrived at the Yacht Club de Monaco with little idea why he was actually there.

“Come and meet a group of people,” Dennis Frederiksen from Fraser had told the co-creative director at Dutch studio Vripack. “You won’t regret it.” Frederiksen, a broker who has sold £1 billion of boats in a 40-year career, is a meeting worth taking for any superyacht designer, no matter how cryptic the brief.

The group Hoekstra would see was Foundation Zero, a set of impact investors whose headline ambition was to create the world’s first fossil fuel-free superyacht: no combustion engine, no fuel tanks. But it would be as much about the journey to get there as the finished project: outside-the-box solutions; brave experiments; new (and expensive) testing; capacious data collection and analysis.

An ecosystem of creative engineering and exciting leads, all of which would be gifted to others via open-source publishing. Nearly five years later the yacht, which is in the outfitting phase at Vitters Shipyard, is a showstopping proof of concept.

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

TOM VAN OOSSANEN

The members of the foundation knew yachting – that’s why they wanted to develop sustainable marine hospitality solutions. They also knew that a bare bones “test boat” wouldn’t be much use to an industry whose customer base expects top level luxury; comfort and appealing aesthetics had to be built in, no compromise.

The leaders of the foundation had the germ of a plan for Project Zero in 2019, but when they enquired with yards, most were reluctant to take the risk.“There are a lot of reasons why [a yard] should not do the project. There is a lot of uncertainty involved,” says Hoekstra.

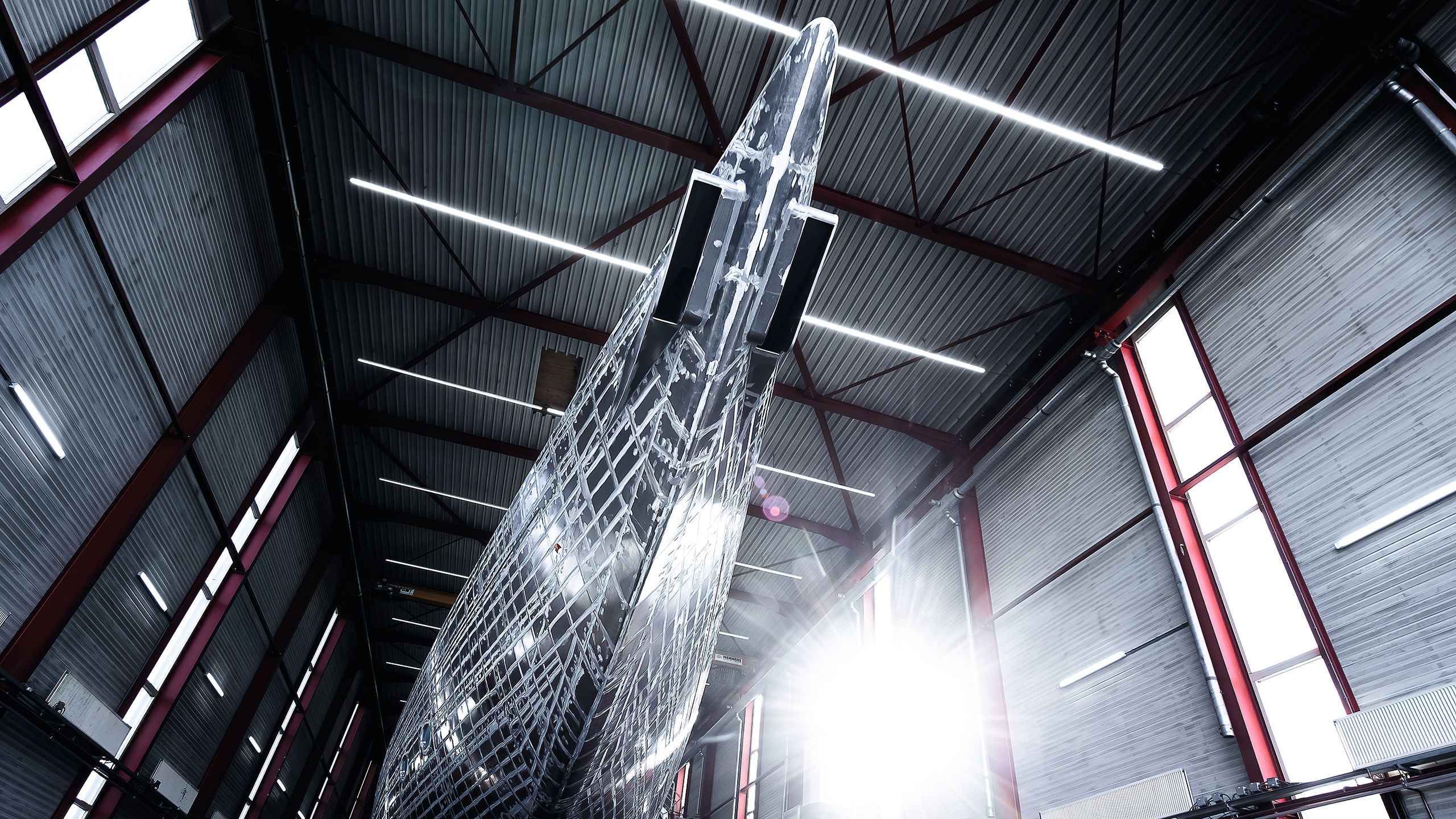

TOM VAN OOSSANENProject Zero under construction at Vitters shipyard in the Netherlands

TOM VAN OOSSANENProject Zero under construction at Vitters shipyard in the Netherlands

At that July meeting at Port Hercule, he was one of the first who thought it might be possible. He’d been participating in the Yacht Club de Monaco’s Energy Boat Challenge (Vripack is a founding member of the competition), in which teams of young people design and race small fossil-fuel-free boats, supported by established designers.

As a result, he’d been tinkering with solar power and was curious to take it further. Vripack and the foundation hatched a more defined plan and assembled a Dutch dream team: sailing superyacht builder Vitters; Dykstra Naval Architects, responsible for a roll call of sailing innovations including Maltese Falcon’s Dynarig; and Eduard van Benthem, engineering manager at Foundation Zero. To this core they added coders, data analysts, and a physicist called Bob.

ORGANISATION

“One thing that is quite different [from a conventional project is] that even at a fairly advanced stage, critical choices still need to be made, which we normally would have already laid down, purchased, engineered, prepared,” says Louis Hamming, CEO of Vitters.

As this is a project where technology will evolve during construction and even after, to allow physical testing to bear out theoretical innovations, it requires an unorthodox approach.

Rather than being a line from A to B, the project is “a big matrix”, Hoekstra says. Hamming describes it as a straight line from A to B but with “a few loops in the path”.

He notes that where the yard might have five or six engineers on a project this size, they now have eight to 10 people working on developing systems alone, and later, during the finishing stage, they will have 120 to 150 on the project in total. “We really work as a group, not separate parties who have their own demarcation – we have to work together,” says van Benthem.

MARLOES BOSCH FOTOGRAFIE

MARLOES BOSCH FOTOGRAFIE

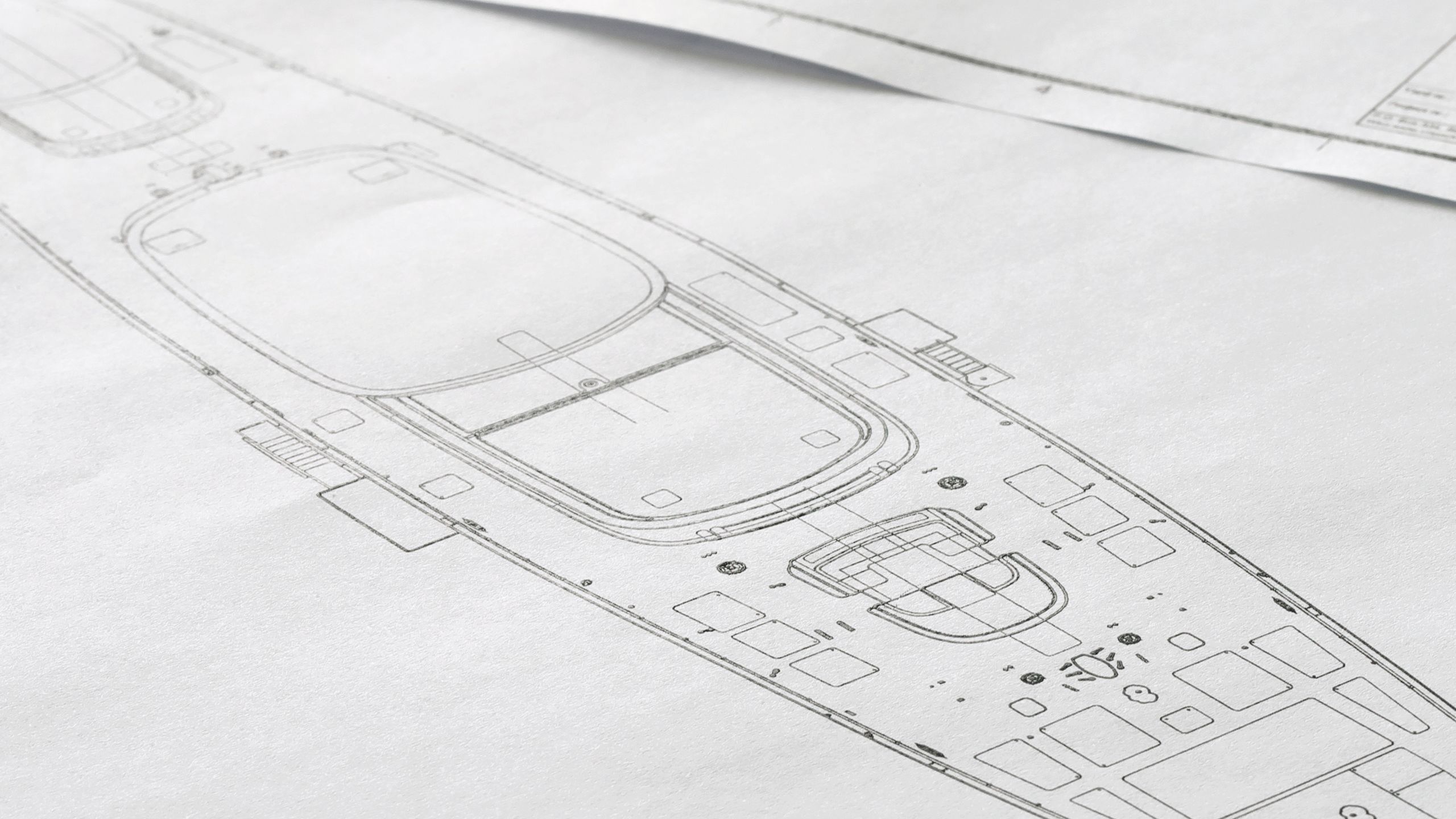

A regimented approach where specialisms are siloed just wouldn’t foment the kind of innovation that was required. For example, says Dykstra naval architect Mark Leslie-Miller, “I’ve put in an allowance, saying you can spend 40 tonnes on batteries [but] if it’s going to be more please let me know [because it will affect the weight distribution].”

If that changes, as batteries are developed, Dykstra might adjust the hull calculations as a result. Or they might decide that the hull can go no further, and lighterweight batteries need to be found.

But they want to get the basics right at the beginning – cabling, piping, insulation, naval architecture – “and keep the rest modular”, says van Benthem. “That’s really something that we’d like to achieve: to have a platform that during the lifetime of the boat will become even more completely off-grid.”

A revolutionary approach to energy would have to define Project Zero – and they had only the sun, the wind and the water to work with

THE ENERGY CHALLENGE

The operational profile for the yacht they would create was a two-week charter that didn’t use any fossil fuels and didn’t stop in port to recharge.

Current capabilities were nowhere near two weeks. “It was something like 48 hours [for a 69-metre ketch],” says Hoekstra. Leslie-Miller adds: “Most yachts with batteries use them for an overnight silent period of about eight hours.”

They looked at the weekly energy cycle on a 69-metre sailing yacht, and how much clean energy would be needed to scale up to 14 days of independence – how much could be generated and how much could be stored. The figures did not look good.

To hit their goal for Project Zero, they would need to dramatically reduce energy requirements and increase energy generation compared to a conventional 69-metre ketch – all without compromising onboard lifestyle or total freedom of movement. A revolutionary approach to energy would have to define Project Zero – and they had only the sun, the wind and the water to work with.

HEAT

“One of the early considerations that struck us was that a lot of energy use on board has to do with heat, either getting rid of it – cooling, air conditioning – or heating up water for showers and laundry. It is 70 to 80 per cent of [non-propulsion] energy use,” says Leslie-Miller.

This traditional approach uses electricity to manage heat – to warm things up or cool them down. One of the most radical decisions the team made was to rethink that.

“We split the energy needs of electrical and thermal into two different groups and those two worlds don’t collide,” says Hoekstra. “Making anything hot or cool by using electrical power takes so much energy, so it’s actually a very inefficient way of doing it.”

Instead, they needed to develop heat exchange between various systems, making use of inverse heat-pumps. In terms of heat reduction, a logical first step was preventing the sun from heating up the boat in the first place, so they insulated the deck and laid cork on top.

TOM VAN OOSSANENDykstra’s experience working on 106m Black Pearl’s naval architecture came to bear with Project Zero’s innovations

TOM VAN OOSSANENDykstra’s experience working on 106m Black Pearl’s naval architecture came to bear with Project Zero’s innovations

They also addressed what Hoekstra calls “cold bridges”: connections in the structure where heat, in this case, could leak through. They found that these points compromise insulation catastrophically.

“You can put on as much as you want but the metal-onmetal will guide the heat straight through,” he says. They therefore looked at these connections between steel girders, replacing hard metal pillars with ones that didn’t conduct heat. Data modelling – a central part of Project Zero, which has often confounded received wisdom – confirmed a dramatic heat reduction.

But all this sun beating down onto a boat was also useful. While solar panels generally only harvest about 20 per cent of the energy influx, Bob the physicist had an idea to supercharge them.

“He said that we have these very cool new solar panels and they can get really hot, so if we have some liquid flowing over those and we harvest that water then we can get very high temperature, high-grade, heat energy,” LeslieMiller recalls.

Cooling systems on board produce a lot of warm-ish water – 30 or 40 degrees C – but the energy is too dissipated to be of much use. “When you’ve got 80-degree water then you’ve really got something,” says Leslie-Miller. Then you can make shower water, do laundry, but you can also drive an A/C system: you can actually use thermal energy to alleviate heat problems.

Like the best solutions, it’s simple and elegant. And it avoids the energy loss of a more complex traditional solar/electrical system. Bob said he thought their special panels could harvest 60 per cent in heat.

“We were like ‘Sure, Bob, because you’re behind your computer calculating that, it makes sense. But that’s not going to happen,’” recalls Hoekstra. Cue six months of solar panel testing with thermal sensors at Vitters. Bob was right: 60 per cent. “We were like, ‘Wow, it works!’ And Bob was like, ‘Yeah, I think we can get a couple more out of this.’” Everyone loves Bob.

HYDROGENERATION

Managing and harvesting thermal energy was a big win, but the team knew that the most bountiful energy was to be found in hydrogeneration. “In these [large sailing] yachts there’s a vast amount of energy in the flow,” says Leslie-Miller.

“We calculated that the amount of power that’s in the sails while we’re trogging along over the ocean is approximately equal to one of these large 1.5-megawatt windmills.”

You can’t pick up all of that energy in the water, or the boat would stop moving – but you can take quite a bit without much effect on performance, and use it to replenish electrical batteries.

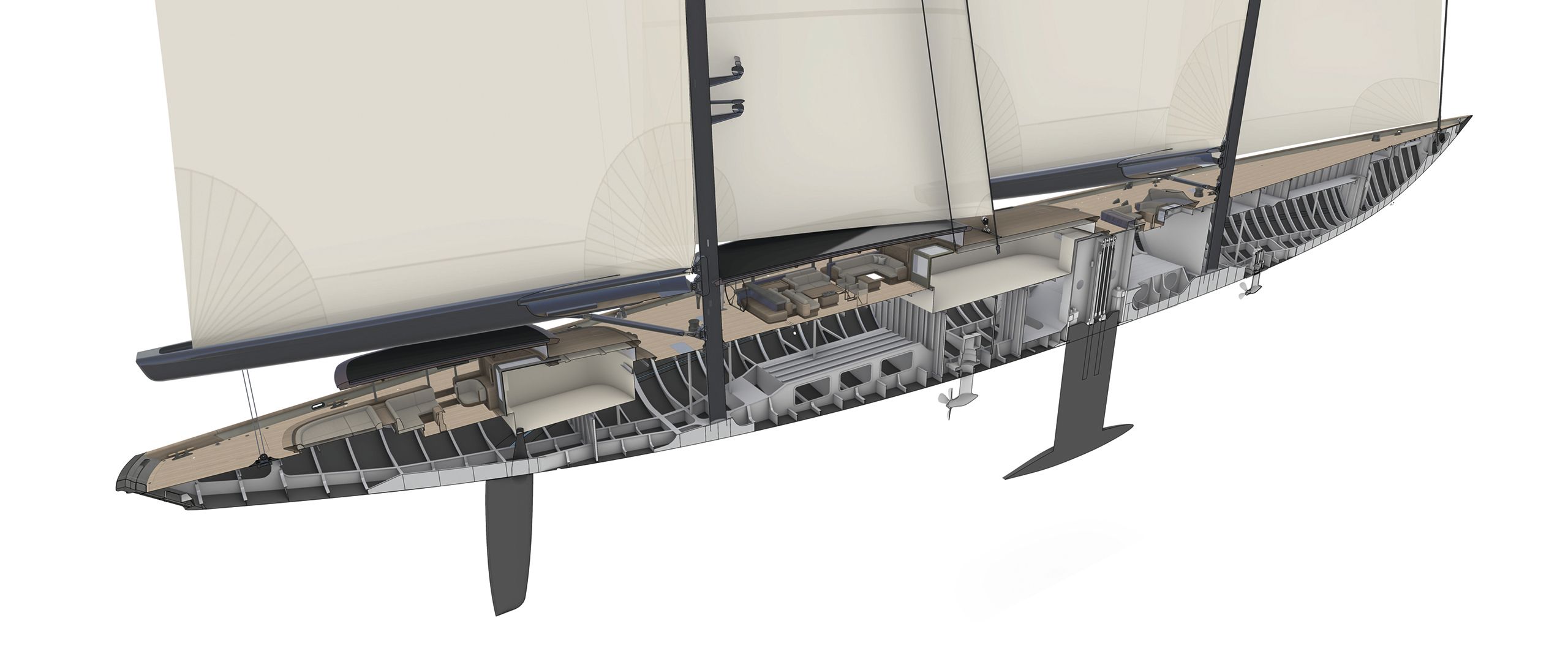

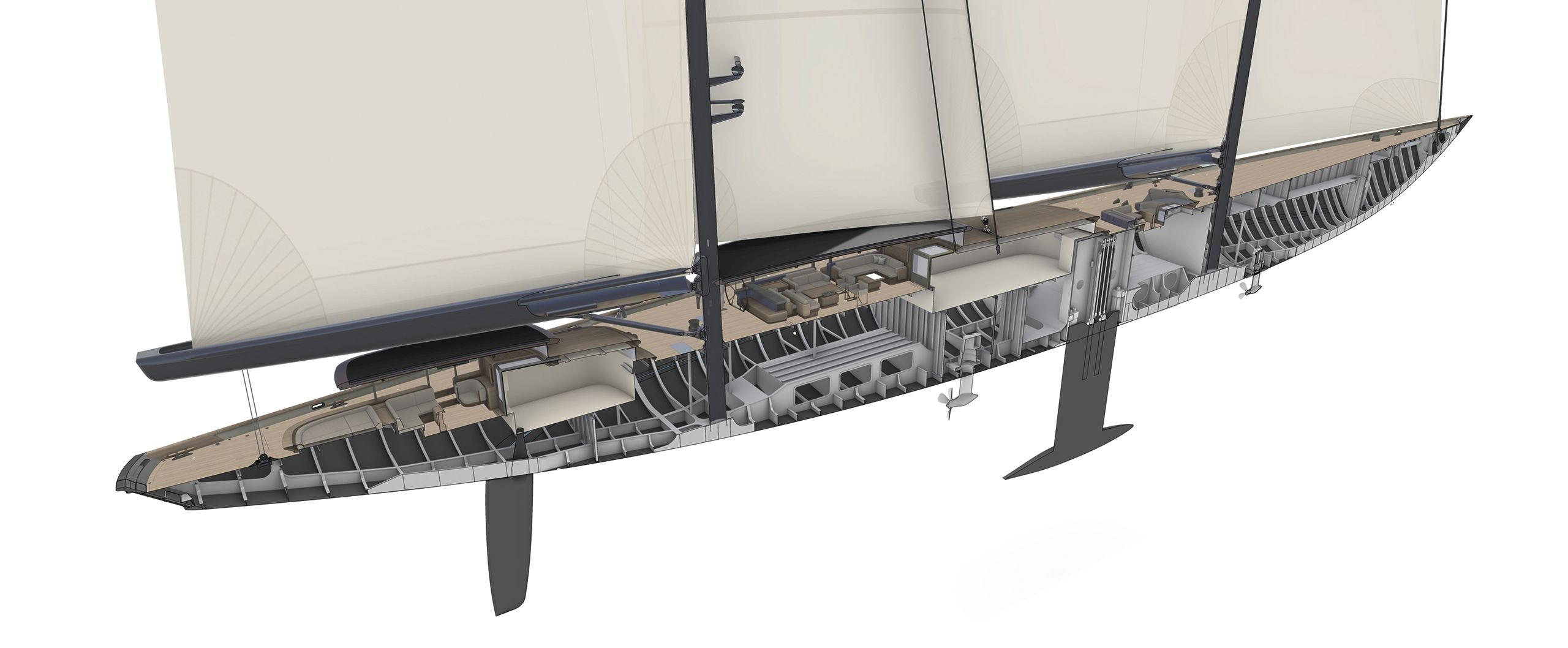

“We’ve done that on a few projects before – Black Pearl has that capability, and Perseverance,” Leslie-Miller says. “What we found though is that in order to harvest a lot you basically need big propellers.”

After testing many different configurations, and considering how they would interact with thrusters, the team chose forwardfacing props and a third quadrant propeller, a solution that Hoekstra says has never been employed in superyachting before.

TOM VAN OOSSANENProject Zero’s hull is rolled into Vitters’ shed at Zwartsluis for 18 months of fitting out ahead of its launch and sea trials in 2025

TOM VAN OOSSANENProject Zero’s hull is rolled into Vitters’ shed at Zwartsluis for 18 months of fitting out ahead of its launch and sea trials in 2025

It’s also a nice nudge to sail more. “During a week of sailing during a charter, there will be some afternoons when the breeze is on and then they’ll just say, ‘Come on guys, we’re a bit low on batteries, we’ll recharge,’ and set all the sails, take it for a spin and fill them up,” says Leslie-Miller.

In terms of its operational profile, Project Zero is designed to be a go-anywhere yacht, with a sailplan able to be operated easily by a limited crew, well-balanced and very controllable in all conditions because, as Leslie-Miller points out, if the weather isn’t playing ball, “you don’t have the luxury to lower the sails and put the hammer down [on a diesel engine], like a lot of sailing yachts currently do”.

They worked with the Wolfson Unit at the University of Southampton on the sailplan and optimised the hull shape with Emirates Team New Zealand (the America’s Cup team).

Velocity predictions show that the yacht will top 16 knots fairly easily. Depending on wind strength and sail direction, it could rack up about 200kW of electrical power via hydrogeneration: “That’s about 10 times the total energy use on board,” says Leslie-Miller.

STORAGE

You can harvest as much energy as you like, but the time for which it can power a boat will be defined by how much of it you can store – and here, too, thermal and electrical energies are sequestered. For thermal energy, land-based architecture is already using batteries that make use of natural materials.

“We’re prototyping with a canister containing two kinds of salt,” Hoekstra says. “We heat up the salt – it melts, goes into another phase, but it takes a long time before it becomes solid again.”

In terms of size, he compares it to a diesel daytank on a 500GT yacht: big but workable. The challenge now is ensuring their salt battery works at sea because those designed for land don’t enjoy movement (there are therefore some salt batteries swinging away in Project Zero’s R&D space at Vitters).

The boat will also need electrical batteries on board to store electrical energy harvested from the sun and water. “But it mustn’t be big and heavy and you want to have a system that is also safe. Within the group we always say ‘OK, do you dare to sleep on top of it?’. If not, you have to look further,” says van Benthem.

The Lloyd’s- or DNV-approved systems already on the market weren’t dense enough for their needs. And with electric cars and buses hoovering up all the conventional batteries the market can produce, it wasn’t worth big manufacturers’ time to work on the needs of a bespoke yacht project. Instead, the team turned to a German battery specialist, and their work is ongoing.

VIRIPACK

VIRIPACK

The wood used on deck is Tesumo, an engineered product made from a fast-growing African tree that matures in 50 years, roughly one-third the time of premium teak. Tesumo has the same properties as teak in almost all important respects, but is sustainable

VIRIPACKThe wood used on deck is Tesumo, an engineered product made from a fast-growing African tree that matures in 50 years, roughly one-third the time of premium teak. Tesumo has the same properties as teak in almost all important respects, but is sustainable

VIRIPACKThe wood used on deck is Tesumo, an engineered product made from a fast-growing African tree that matures in 50 years, roughly one-third the time of premium teak. Tesumo has the same properties as teak in almost all important respects, but is sustainable

LOOKS

The yacht has slender, classical lines, with a few twists. “We’ve introduced these round corners and shapes with these big bullnoses which are very 1930s,” says Hoekstra. Close up it’s a clean design and the way the wood has been used on deck – bare Tesumo wood, a sustainable teak alternative – is distinctly contemporary.

They worked with Dykstra to keep the deck uncluttered and free of tracks and hatches (or at least to appear that way). A lot of tech is hidden in plain sight. The solar panels are integrated into the top of the fixed bimini that covers the deckhouse.

This is thicker than it might have been, to accommodate all the tech, but creating a shadow line – a visual gap between the bimini and its supporting pillars – gives the impression that it’s lighter, thinner, even floating.

“You want to have a system that is also safe. Within the group we always say ‘OK, do you dare to sleep on top of it?’ If not, you have to look further”

Inside the deckhouse, car-style retractable windows will turn the space from indoors to al fresco at the touch of a button. While the yacht does offer A/C for extreme temperatures, it also has floor- and ceiling-cooling systems for everyday use, which work via embedded pipes carrying coolant, which cool aluminium panels.

“You don’t have air pumping around, flowing around in your cabin,” says van Benthem. “It’s just cool and comfortable and it consumes less energy.”

What’s next? Vitters has finished the hot works, started the isolation and systems, and the interior builder is preparing and constructing the interior on location. Launch is slated for spring/summer 2025, with substantial sea trials to follow.

Just as importantly, the research, calculations, drawings, designs and even routing software are already filtering up online (foundationzero.org). The hope is that others, particularly startups that might not have the funds to do this initial research, will pick up the threads and run with them – producing the green innovations that will transform hospitality on land as well as at sea.

It may also pique the interest of owners to drive yards in this direction. It looks as if Project Zero is a yacht destined to make some waves.

First published in the June 2024 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.