ON

BOARD

WITH

Adam Alpert

On board 60m Perini Navi Seahawk with owner Adam Alpert

Sailing and aviation are parallel passions for the owner of 60-metre Seahawk, but getting his hands dirty with philanthropic projects helps keep his feet on the ground, discovers Caroline White

“We fly because of the weather, not despite it,” says Adam Alpert, a passionate commercial pilot and the owner of 60-metre Perini Navi sailing yacht Seahawk. That motto, which he first heard from Robert Buck, TWA’s chief pilot when Howard Hughes owned the airline, applies equally to his life on board. “A windy day for a motor yacht is an inconvenience, maybe even threatening. For us, it’s a blessing. It is magnificent to really sail that boat – an empowering feeling.”

However, alongside the visceral gratification is an intellectual pleasure. “There’s a difference between knowing the name of something and understanding how it works but most people confuse those two things,” he says. “Flying teaches you this and sailing does too, especially complicated sailing boats like Seahawk. For curious people, it is kind of fun because you really can figure out what’s going on when you turn that key, so to speak.”

Intellectual curiosity has been a thread running through Alpert’s life, from his degree in mathematics and computer science to his first job in nuclear power, his second in aerospace and his later career as owner and vice-president of BioTek Instruments – a large multinational life-science tools company until his retirement in 2018.

That was the beginning of perhaps the biggest scientific adventure of Alpert’s life, the purchase of Seahawk as a platform for an ambitious programme of world-roaming charity work with a scientific bent. Alpert spent his early years in Chicago, where his father was an academic and his mother a former actress. When Alpert was 10 years old, his father was offered the chairmanship of the Department of Physiology at the University of Vermont.

“I had two choices: I could be a farmer or I could go into the hospitality industry”

“He was 42 or 43 years old,” recalls Alpert. “I think, at the time, he was not only the youngest chairman in the country, but the youngest chairman ever.”

The Green Mountain State was quite a change for the family. “Even today, it’s a very rural part of the country and back in the 1960s, it was truly agrarian. I recall being told in eighth grade that, fundamentally, I had two choices: I could be a farmer or I could go into the hospitality industry.”

KATHERINE WELLES - STOCK.ADOBE.COM The University of Vermont, where Alpert’s father was a professor

KATHERINE WELLES - STOCK.ADOBE.COM The University of Vermont, where Alpert’s father was a professor

Alpert begged to differ and, after graduating from the University of Vermont, he got a job as an engineer at Hayward Tyler.

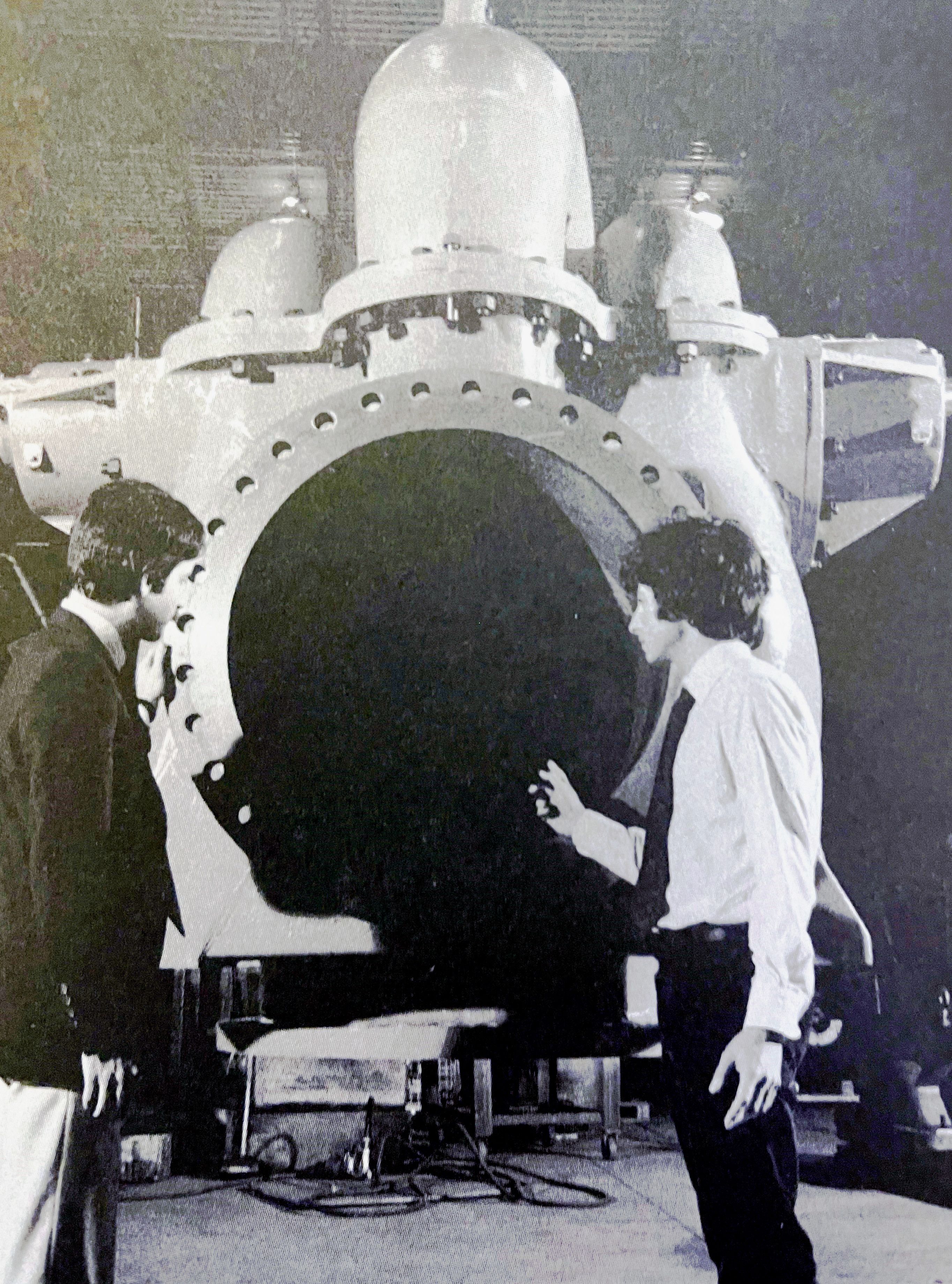

“We built cooling systems for uranium-powered reactors. We were famous or infamous, depending on whether you think we saved the day or not, because our pump designs were installed at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania,” he says.

NORMAN SCHREIBA young Alpert with a Hayward Tyler pump

NORMAN SCHREIBA young Alpert with a Hayward Tyler pump

In 1979, the nuclear reactor nearly melted down, a disaster avoided because the plant's emergency core - cooling system (which incorporated Hayward Tyler pumps) continued to run. “Despite the operator’s best efforts to kill the back-up system – including trying to access the pumping facility itself – the pumps remained partially operational.”

With the Eastern Seaboard safe from nuclear destruction, Alpert moved on to a role in aerospace. “We did some structural analysis on the Space Shuttle, which is an interesting machine. I worked on the nozzle structure, a piece of the big liquidfired main engines,” he recalls. “Rocket science – I can say I did that!”

In the mid 1980s, Alpert entered the family business – reluctantly at first – as a software engineering manager.

“Computer science was a discipline in its infancy and very exciting,” as was life science, a new challenge that was learned and loved as a result of joining the company. BioTek “builds the tools that make it possible for our scientist customers to conduct their research more effectively, as well as cheaper and quicker.” The company is a leader in livecell imaging used for applications that range from drug discovery to catching the bad guys through crime-scene investigation. Agilent Technologies bought BioTek Instruments for $1.16 billion (£908m) in 2019.

GISELA ALPERTThis Boeing-Stearman biplane is only one of keen pilot Alpert’s many aircraft

GISELA ALPERTThis Boeing-Stearman biplane is only one of keen pilot Alpert’s many aircraft

Rising through the ranks to managerial level, Alpert lived in London, Paris, Milan and Japan. Through all of this, aviation was Alpert’s true love. He’d graduated from hang-gliding (and launching his little brother off a balcony in a home-made plane) in Chicago to gliders and then the real deal.

He owns hangars loaded with planes, from a Grumman Widgeon G44 seaplane, to a Cessna Skywagon, an L-19 Bird Dog, a Boeing-Stearman biplane and his current love, a Gulfstream G280. He’s qualified up to commercial level for all the aircraft in the fleet, including a Bell Jet Ranger helicopter.

But sailing has been a parallel passion. Alpert sailed dinghies as a teenager, crewed larger sailing boats and par ticipated in club races on Lake Champlain on the New York/Vermont border.

“The family owned several smaller sailboats over the years including Lionheart, a J/105 (11 metres),” says Alpert.

Sailing with his father was instructive. “Dad had, I think, a very insightful approach to his racing. He would try to recruit the best people and then he would let them do their thing. He was good at putting the talent to work in the right way. Not so many owners are like that.”

KERYN RANKIN

KERYN RANKIN

When Alpert retired, he and his wife, Gisela, decided to expand rather than reduce their horizons

What father conveyed to son was illustrated during a race when the Alperts’ J/105 “very gently touched another boat at the mark. The owner of that boat, who was also the captain, was offended by this to a very intense degree. He jumped off of his boat and onto the bow of our boat. He ran back to the cockpit and slugged the guy who was at the helm, who he thought was me, because the way he ran his boat was that the helmsman and the owner were the same person.”

It was certainly ungentlemanly behaviour, so a yacht club trial (yes, that’s a real thing) ensued and the angry owner was stripped of his membership. If he had run his boat like Alpert and his father did, he might have been in a better mood – or at least realised he was punching the wrong man.

When Alpert retired, he and his wife, Gisela, decided to expand rather than reduce their horizons. “We had a vision of accessing the world in a different way. We recognised that a boat offered the ability to engage a little bit more, so you could get to know a place better than you would if you, let’s say, descended by jet airplane.”

A boat also opens up remote destinations that would be difficult to access. The Perini Navi sailing yacht Seahawk ticked all their boxes – she was an oceangoing yacht with the right kit, offered a luxurious home away from home and, as Alpert notes, “let’s face it, a giant ketch is just romantic. It’s a beautiful thing to behold.”

However, the Alperts wanted to be more than just tourists – there was a mission, complete with a mission statement: to harmoniously impart science-based strategies for the benefit of the coastal communities so engaged.

“The Seahawk concept has owners, guests and crew investing effort to improve the lives of those encountered along the way,” says Alpert. “This is not just cheque writing, which is something we’ve done a lot of over the years. The goal is to become actively involved in the charity work that’s supported, close -up and personal.

“And there is much merit to this approach. It delivers a more effective outcome due to the real-time feedback mechanism afforded by actually being there, while also providing an excellent opportunity to learn more about the people and places visited.”

ADAM ALPERTThe Alperts "recognised that a boat offered the ability to engage a little bit more, so you could get to know a place better”

ADAM ALPERTThe Alperts "recognised that a boat offered the ability to engage a little bit more, so you could get to know a place better”

The strategy also has local communities defining the purpose and scope of the work.

“This idea is very important because even assuming great science and humanitarian aid that is worthy, the lack of support from local leadership to help implement it most assuredly dooms the enterprise to failure. It should also be noted that the people closest to the problem know things that can be very important when trying to figure out what to do.”

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

ADAM ALPERT

Anti-clockwise from top left: Galápagos children ready to learn to sail; tagging project leader Dr Alex Hearn; tagging sharks; the Alperts and YachtAid Global provided Optimist dinghies for the Galápagos sailing school

“The science said make this a marine protected area... and there will be more fish for the people in the countries”

Although science will not always solve conflicts where parties are really “dug in”, it can, says Alpert, promote co-operation through its collegial nature.

“ The best science is actually conducted between individuals, not universities or governments.” In the work tagging sharks, Seahawk carried a scientist from Hawaii who worked with a scientist in French Polynesia.

“There was a cultural gap there perhaps, but the common ground for them is that they’re both interested in solving some of the problems related to fishing and trying to understand migration patterns. To that end, they worked very nicely together.”

ADOBE STOCK The Alperts' time in Bonaire turned out to be something of a blessing

ADOBE STOCK The Alperts' time in Bonaire turned out to be something of a blessing

Seahawk’s mission has taken the Alperts to the Caribbean, the Mediterranean (Croatia, Italy, Spain, France, Gibraltar), the Sea of Cortez, western Baja, the Galápagos, the Pacific islands of San Benedicto and Socorro, Costa Rica including Cocos, French Polynesia and, most recently, Fiji. As well as science projects, they have carried school supplies to remote Fijian islands, where the Alperts learned about the educational challenges in the region.

Seahawk also inaugurated a swimming and sailing programme in the Galápagos Islands (where only 30 per cent of residents can swim), with four Optimist dinghies provided by Seahawk and YachtAid Global, and built a shelter to house stray dogs for adoption on Bonaire.

“The people who were helping see the owner’s involvement as being something special and it’s viewed positively”

It’s undoubtedly valuable work, but would it be more effective to just write a big cheque? “There are some practical advantages to being closer to these projects,” says Alpert. “When you’re personally involved, you really get to understand the needs better. I mean some things don’t work, or don’t work well, but you learn things, you get better. It’s about continuous improvement, so the next time you know a little more, you design the programme a little better.

“One other advantage – I can’t prove this systemically, but it’s just been my experience – is that there is something magical about showing up to help with the title of ‘owner’. And I’m not being self-aggrandising here. I’m probably the least talented of the contributors who get involved in this, but I do know that the people who were helping see the owner’s involvement as being something special. Maybe it ’s confidence -inspiring at some level. Maybe it says ‘these guys are not just placating us with money’. The willingness to actually engage is viewed very positively.”

ADAM ALPERTGisela Alpert and a four-legged friend

ADAM ALPERTGisela Alpert and a four-legged friend

Alpert is a passionate advocate for other boats to get involved in this kind of work. There are four or five yachts now helping with the swim and sail programme in the Galápagos, a fact Alpert finds enormously gratifying. And why not? Superyacht owners tend to be highly intelligent, ambitious people who are often seeking novelty and adventure.

“In this spirit, my hope is that more yacht owners will elect to do something similar,” says Alpert.

First published in the February 2023 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.

FLY BUY

Adam Alpert's tips for purchasing a private plane

Destination known If 20 per cent of your destinations account for 80 per cent of your trips, convenient access to these places is key. Be sure to check which planes can reach these destinations both conveniently and economically.

Determine annual usage Chartering or using a jet card would make more sense if you plan to fly less than 200 hours per year (equal to about 12 round trips from New York to London).

A proprietary flight department or a fractional arrangement? Comparatively expensive but simple to accomplish, turnkey fractional deals involve the client purchasing management services plus a share in an aircraft from the company’s menu. A proprietary flight department requires management resources, pilots, training, owned/leased aircraft, hangar facilities and expert guidance for set-up and operation. It is more complex but costs less and in most cases delivers a better product.

New versus used aircraft New aeroplanes come with a valuable warranty and offer tax advantages. There is also greater opportunity for customisation but negotiate all modifications prior to signing. Expect any post-deal requirements to be very expensive. Used planes are more affordable but “used” also implies higher operating costs. And never consider a jet plane older than 15 years. Many banks are reluctant to finance beyond this age, limiting potential buyers at resale.

Adam Alpert is author of We Have a No Crash Policy! A Pilot’s Life of Adventure, Fun, and Learning from Experience. $20, asa2fly.com

LOCKDOWN IN BONAIRE

By Adam Alpert

GREG BALFOUR EVANS - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO The Alperts' three-day visit to Bonaire became more like a four-month stay

GREG BALFOUR EVANS - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO The Alperts' three-day visit to Bonaire became more like a four-month stay

Our story begins in early March 2020. Originating out of the BVIs, Seahawk’s sailplan had us on a close reach for the 2.5-day journey from Norman Island, BVI, to Bonaire, a sovereign part of the Netherlands. The timing for our departure from the BVIs was fortuitous. The country was beginning to close to visitors and movement within was soon to be restricted. Bonaire would remain open until two days after our arrival on 12 March. When the last cruise boat departed, that was it and the island closed to all new visitors. Evacuation flights were organised for those vacationers caught unaware of the impending quarantine. Soon after that, the airport closed. As for us, we were stuck. Our three-day visit became more like a four-month stay.

During their enforced stay on Bonaire the owners and crew of Seahawk used as many local businesses as possible, such as the local yoga instructor

During their enforced stay on Bonaire the owners and crew of Seahawk used as many local businesses as possible, such as the local yoga instructor

Our stranding turned out to be something of a blessing. At that time, there were no infections on the island, so life went on more or less as before. The influx of government money kept everyone afloat, at least for a while. One could still buy an ice cream at Gio’s Gelateria in Kralendijk. Many of the restaurants stayed open too. Bonaire became kind of a bubble, insulated from the outside world.

Among our goals while there for this indeterminate period was to patronise every business that would have us. Activities ranged from exploring the island’s extensive underground cave system and riding ATVs in the desert to diving the many excellent sites protected by STINAPA (Stichting Nationale Parken). We visited all the restaurants still open, took a guided kayak tour of Bonaire’s famous mangrove marsh and hired the local yoga instructor to provide private lessons to us and our crew twice a week.

ADAM ALPERTDuring their stay, they built the Puppy Village at the animal shelter

ADAM ALPERTDuring their stay, they built the Puppy Village at the animal shelter

We also got involved in the local animal shelter, initially by volunteering and later in the form of implementing a new construction project to house dogs for adoption. It was this project that gave birth to The Seahawk Family Puppy Village.

I am especially proud of the Puppy Village. Much credit goes to our captain at the time and chief stew Keryn Rankin, who championed and managed the work. We made good labourers and all the funding came from our foundation.

GISELA ALPERTAdam Alpert said he was especially proud of the Puppy Village

GISELA ALPERTAdam Alpert said he was especially proud of the Puppy Village

The Puppy Village also served as a nice prototype for how to help in a constructive way. The key is buy-in from local supporters, in this case the Bonaire animal shelter workers plus its board and leadership. We also made a concerted effort to acquire goods and services locally when possible, which was part of the reason the project enjoyed so much visibility among the islanders. It created increased community involvement and volunteering. The rate of adoptions – really the best indicator of success – went up too. Seahawk made a lot of new friends as a consequence and some stay in contact with us, even to this day.