NATIONAL TREASURE

How Carl Allen recovers riches from the Bahama Banks by superyacht

For years, yacht owner Carl Allen has dived Bahamian waters for buried loot. Now he's sharing his spoils so everyone can enjoy them, discovers Tom Ough

CHAD BAGWELL - ALLEN EXPLORATION

When we speak, the superyacht owner Carl Allen is exhilarated. He has had a week to remember. He was at a wedding reception in Fort Worth, Texas, when Dan Porter, the project manager of his exploration company, flashed up on his phone screen. “I always get excited when I see Dan’s number come up,” he says. Allen ran somewhere quiet to hear the news.

Diving off his superyacht, his exploration team had discovered two cannon carriages about 12 metres under water, picked up first by magnetometer, then with a diver’s hand metal detector. The cannons’ wood had deteriorated but their metal remained.

Crucially, the cannons were only about 30 metres from each other. “That means that we’re possibly near the centre of the ship,” says Allen. It means that he and his team might be near the “main pile” of the shipwreck they’ve been diving for many years now – or, what you might call “the mother lode”.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONCarl Allen wanted to be a treasure hunter since he was a boy

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONCarl Allen wanted to be a treasure hunter since he was a boy

Perhaps the cannons weren’t as exciting as the 60-carat emerald Allen once unearthed (“I thought it was a piece of a Heineken bottle!”), or a brooch they found with a 20-carat cabochon emerald in the middle, with two knights of Santiago crosses on either side of it, all gold. But they mark a significant development in Allen’s story – not least for someone who says he’s dreamed about finding treasure his whole life.

Allen’s story is one that many a yacht owner can relate to. Aged 50, he decided it was finally time to sell the company he’d built up from scratch and, after taking call after call in a New York hotel room with his wife Gigi, the deal was finally done.

In May 2016, the business – manufacturing rubbish bags and the plastic inners that line bins – sold for $300 million (£237m), and suddenly Allen was faced with the prospect of decades of leisure time stretching out ahead of him.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONHis Allen Exploration fleet includes Gigi and support vessel Axis

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONHis Allen Exploration fleet includes Gigi and support vessel Axis

What else is there left for a centimillionaire to do other than buy a shiny new yacht and start daydreaming of sundowners out on the ocean? And yet, Allen is no normal owner, and the 50-metre Gigi is no normal boat.

“My wife looked at me, and she said: ‘I know what you’re going to do. You’re going to go treasure-hunting,’” Allen recalls fondly. And she was right. Now, he owns a public museum in Grand Bahama, displaying his finds for all to enjoy. Not that he’s done with exploring just yet…

ANTONY MATHEUS LINSEN-FAIRFAX MEDIA VIA GETTY IMAGES

ANTONY MATHEUS LINSEN-FAIRFAX MEDIA VIA GETTY IMAGES

GWEN FILOSA - FLORIDA KEYS NEWS - MIAMI HERALD - TRIBUNE NEWS SERVICE VIA GETTY IMAGES

GWEN FILOSA - FLORIDA KEYS NEWS - MIAMI HERALD - TRIBUNE NEWS SERVICE VIA GETTY IMAGES

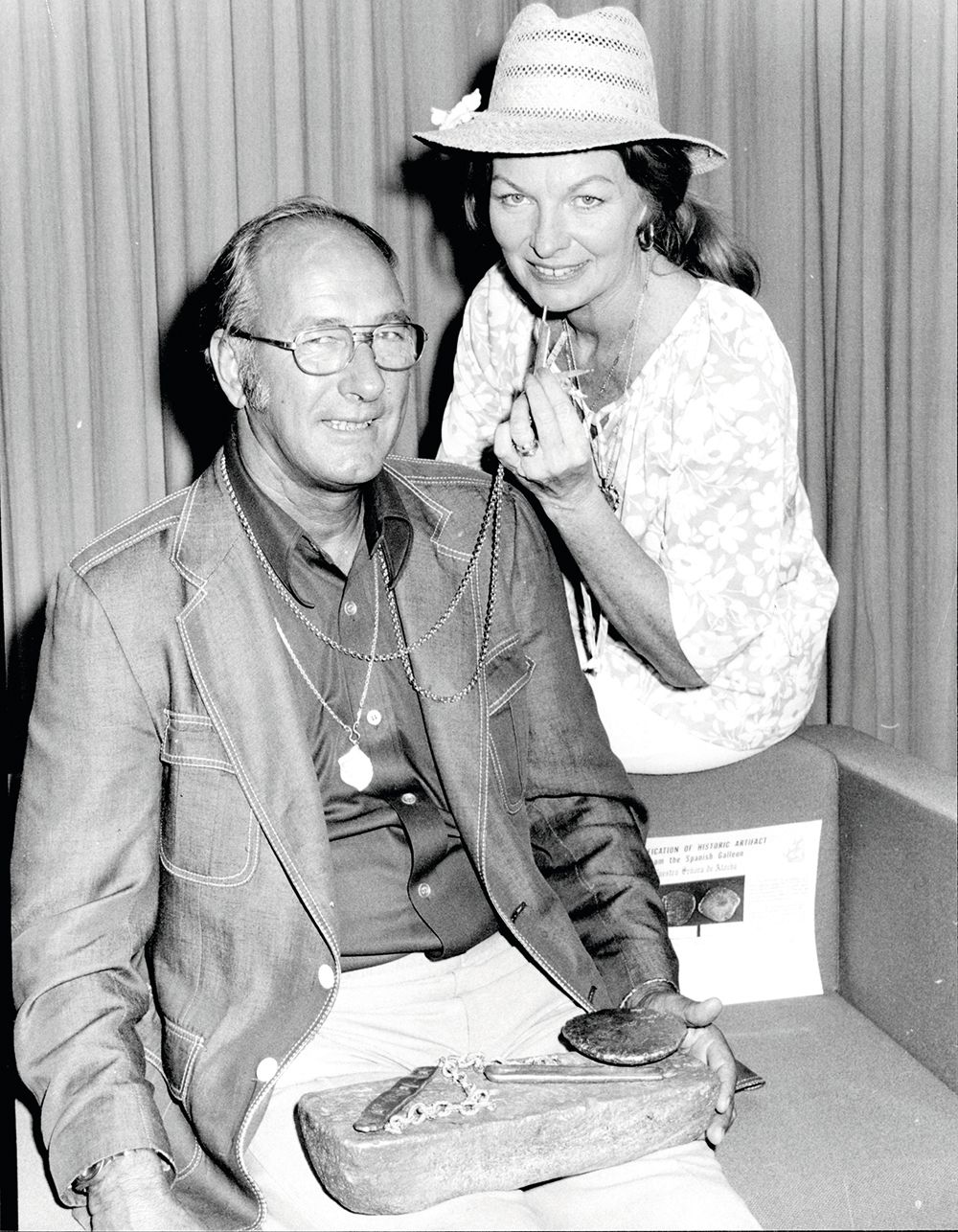

Mel Fisher, left, with wife Deo in 1978; there is a museum dedicated to him in Key West, Florida (right)

His story actually begins centuries ago. The treasure that has become his life’s obsession goes back to April 1647, with the launch of a galleon called Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas – known as “Our Lady of Wonders” in English, or just the Maravillas for short – whose treasure was spilled in a famous shipwreck on Little Bahama Bank.

Centuries later, those same treacherous waters over the Bahama banks beguiled a young Carl Allen. As a boy, Allen had fished and dived in the lakes of New York State and Chicago, and his first trip to the islands came when, at the age of 12, he accompanied his stepfather to Walker’s Cay, the northernmost island in the Bahamas, which is situated on Little Bahama Bank.

Allen recalls being mesmerised by his first sight of the blue-green waters. It would not be his last.

Back home in the States, Allen learned to scuba dive, exploring a flooded mine in Illinois with a friend. Aged 21, the pair visited treasure hunter Mel Fisher’s museum in Key West, Florida.

Fisher was best known for finding the wreck of another richly laden Spanish galleon, the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, in the 1970s and had recovered items worth $400 million.

By chance, Fisher was in his office that day, so Allen and his friend got to speak to him. Asked by the young Allen whether he’d found all the treasure out there, Fisher put his paperwork aside and heaped some sand onto his desk.

DON EMMERT-AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES Fisher found $400m of treasure on the Atocha

DON EMMERT-AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES Fisher found $400m of treasure on the Atocha

Then he pulled out two grains of that sand and pushed them to one side. “Boys,” he said, pointing to those two grains, “that’s what I’ve found.” Then he pointed to the far larger pile. “And that’s what’s still out there.”

Allen was desperate to work for Fisher but his father, who had founded a plastics business, urged his son to return to work.

Allen followed his father’s advice, eventually assuming control of the company, but continued to spend his evenings and weekends reading about shipwrecks.

From the late noughties he studied the Maravillas, “absorbing everything I could get my hands on,” he says, “any titbit of information that fleshed out the story.”

A DOOMED VOYAGE

One of six galleons commissioned by King Philip IV (right) to defend Spain, the Maravillas set out on 10 July, 1654, from southern Spain for Colombia, to take on treasure salvaged from the wreck of another Spanish galleon.

In Havana, the crew took on even more loot, this time contraband, and were then faced with the daunting task of making sure the ship reached home safely with its bounty, avoiding a large English fleet reportedly sweeping through the Caribbean.

They set out on the traditional Spanish convoy route along the northern coast of Cuba before turning into the Bahama Channel, where the Gulf Stream would speed them homewards.

Just before midnight on 4 January, 1656, with most of its crew asleep, the Maravillas ran into shallow waters on Little Bahama Bank, which surrounds the most northern of the Bahamian islands.

A priest who was on board that night hurried onto deck to find the suddenly roused crew in a state of commotion in the dark. “I found some alarmed, others confused, and everyone giving opinions about what should be done,” he later recalled.

The Maravillas crew, aiming to warn the rest of the fleet to change course, fired a cannon. But on turning, the flagship Capitana smashed into the side of the Maravillas.

The flagship’s bow, wrote Father Diego, “broke through our planks from the top of the waterline to the holds, making splinters out of all of them.” In disarray, the Maravillas hit a coral reef, scattering cargo across the seabed – a hoard for many to discover, or try to uncover, for centuries to come.

CHRISTOPHEL FINE ART - UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

CHRISTOPHEL FINE ART - UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

One of six galleons commissioned by King Philip IV (below) to defend Spain, the Maravillas set out on 10 July, 1654, from southern Spain for Colombia, to take on treasure salvaged from the wreck of another Spanish galleon.

In Havana, the crew took on even more loot, this time contraband, and were then faced with the daunting task of making sure the ship reached home safely with its bounty, avoiding a large English fleet reportedly sweeping through the Caribbean.

They set out on the traditional Spanish convoy route along the northern coast of Cuba before turning into the Bahama Channel, where the Gulf Stream would speed them homewards.

Just before midnight on 4 January, 1656, with most of its crew asleep, the Maravillas ran into shallow waters on Little Bahama Bank, which surrounds the most northern of the Bahamian islands.

CHRISTOPHEL FINE ART - UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

CHRISTOPHEL FINE ART - UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

A priest who was on board that night hurried onto deck to find the suddenly roused crew in a state of commotion in the dark. “I found some alarmed, others confused, and everyone giving opinions about what should be done,” he later recalled.

The Maravillas crew, aiming to warn the rest of the fleet to change course, fired a cannon. But on turning, the flagship Capitana smashed into the side of the Maravillas.

The flagship’s bow, wrote Father Diego, “broke through our planks from the top of the waterline to the holds, making splinters out of all of them.” In disarray, the Maravillas hit a coral reef, scattering cargo across the seabed – a hoard for many to discover, or try to uncover, for centuries to come.

By the time he came to sell his own company, Allen was a fully fledged shipwreck obsessive, and soon he founded Allen Exploration (AllenX for short), began buying ships, and started hiring.

He also did his best to convince his wife that this activity was worthwhile. “The best way to get her into it was naming the yacht after her,” he tells me. Gigi, a 50-metre Westport with a deck jacuzzi, a gym, and space for 12 guests and 11 crew, is now the centrepiece of the AllenX fleet.

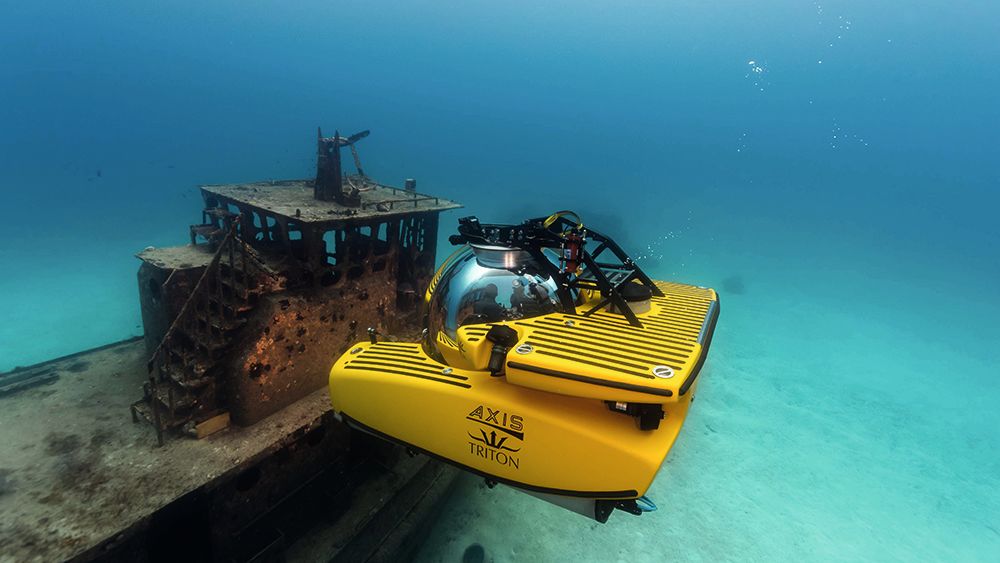

Gigi is complemented by the 55-metre Damen support vessel Axis, which carries an Icon A5 seaplane and a Triton 3300/3 submersible.

Allen’s fleet also includes a Viking sportfisher, two Hells Bay flatboats and several smaller RIBs and jet skis. They can drop anchor at Walker’s Cay, the island that entranced Allen as a 12-year-old, and which he bought in 2018.

“It is special to hear people scream through a regulator and see them holding a gold chain or a big emerald in their hand”

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONAllen and wife Gigi show off a remarkable 400-year-old chain

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONAllen and wife Gigi show off a remarkable 400-year-old chain

Allen couldn’t simply buy a fleet and start salvaging, though. Many countries, including the Bahamas, have strict rules about shipwrecks.

Fisher was one of many treasure hunters accused of profiteering from common heritage, while others have been known to leave wreck sites in damaged states, for example by accidentally dragging their anchors through ship parts.

Those arguments, of course, were far from people’s minds in the 17th century. In the aftermath of the sinking of the Maravillas, there were repeated attempts to salvage the cargo, first by the Spanish and later by others from England, the Netherlands, the Bahamas, Bermuda and France.

Some treasure was brought up by indigenous divers from the Venezuelan pearl fisheries, but the vast majority of it remained lost, and the attempts to rescue it cost salvors another four ships.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE MARAVILLAS

1647 Shipwrights hand the Maravillas on to the Spanish Navy.

1654 The Maravillas leaves Spain for the New World.

1656 In January, the galleon collides with another Spanish ship and sinks off Little Bahama Bank. In June, the wreck is located by Spanish salvors, who manage some limited recovery of its treasure – much of which is then lost in further shipwrecks.

1658 The Spanish record the wreck as being completely submerged within sand.

1972 The Maravillas is located by the marine archaeologist Robert Marx, who takes a significant amount of its treasure.

1990 Herbo Humphreys, another treasure hunter, finds gold bars and the Maravillas Cross, which he then advertises, via an actress friend, on Jay Leno’s TV talk show.

1992 The Bahamian government issues a moratorium on shipwreck salvage licences.

2020 AllenX is granted a licence to recover artefacts from the Maravillas.

2022 The Bahamas Maritime Museum is opened in Freeport, Grand Bahama, exhibiting some of the wreck’s greatest treasures.

1647 Shipwrights hand the Maravillas on to the Spanish Navy.

1654 The Maravillas leaves Spain for the New World.

1656 In January, the galleon collides with another Spanish ship and sinks off Little Bahama Bank. In June, the wreck is located by Spanish salvors, who manage some limited recovery of its treasure – much of which is then lost in further shipwrecks.

1658 The Spanish record the wreck as being completely submerged within sand.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

1972 The Maravillas is located by the marine archaeologist Robert Marx, who takes a significant amount of its treasure.

1990 Herbo Humphreys, another treasure hunter, finds gold bars and the Maravillas Cross, which he then advertises, via an actress friend, on Jay Leno’s TV talk show.

1992 The Bahamian government issues a moratorium on shipwreck salvage licences.

2020 AllenX is granted a licence to recover artefacts from the Maravillas.

2022 The Bahamas Maritime Museum is opened in Freeport, Grand Bahama, exhibiting some of the wreck’s greatest treasures.

Only in the 1970s, three centuries later, did further serious attempts resume. Robert Marx, a US Marine-turned-marine-archaeologist, rediscovered part of the wreck, which had been scattered even further over the years, and brought up thousands of silver coins and many silver bars.

But the Bahamian government, growing increasingly concerned by the prospect of commercial gain at the cost of cultural heritage, withdrew Marx’s licence for recovery.

“The last time somebody touched that was almost 400 years ago ”

In the early 1990s, another treasurer hunter, Herbo Humphreys, used his ship’s propellers to blast sand off the bed of the Little Bahama Bank, exposing what lay beneath. After an apparently unsuccessful day of “blowing holes”, Humphreys and his crew swam to a reef for a dinner of lobster and fish.

It was here that Humphreys saw gold glittering on the top of the reef, the story goes, whereupon the crew found 15 gold bars and the emerald-studded Maravillas Cross, which was once destined to adorn the neck of Queen Isabella, wife of Philip IV and Queen Consort of Spain from 1621 to 1644.

The collection was broken up and auctioned off, and in 1992 the Bahamian government issued a moratorium on shipwreck salvage licences.

Allen Exploration’s first challenge was to get permission to do the exploration. They’d found debris in 2019, but couldn’t excavate it. This time, AllenX told the government things would be different: they’d record every find, be it a shard of pottery or precious jewel, and they’d build a museum for the Bahamian people to house the finds, rather than sell them.

It took until July 2020 for Allen to get a verdict from the government. On a Saturday night, he stood up on the back of Axis to tell Gigi and the crew.

“Let it be known,” he said, “that the future of the Maravillas expedition is now in the hands of Allen Exploration.” There were cheers, beers and cocktails – and a weighty sense of responsibility. What was once a dream was now “a responsibility and a duty”.

CHAD BAGWELL - ALLEN EXPLORATION

CHAD BAGWELL - ALLEN EXPLORATION

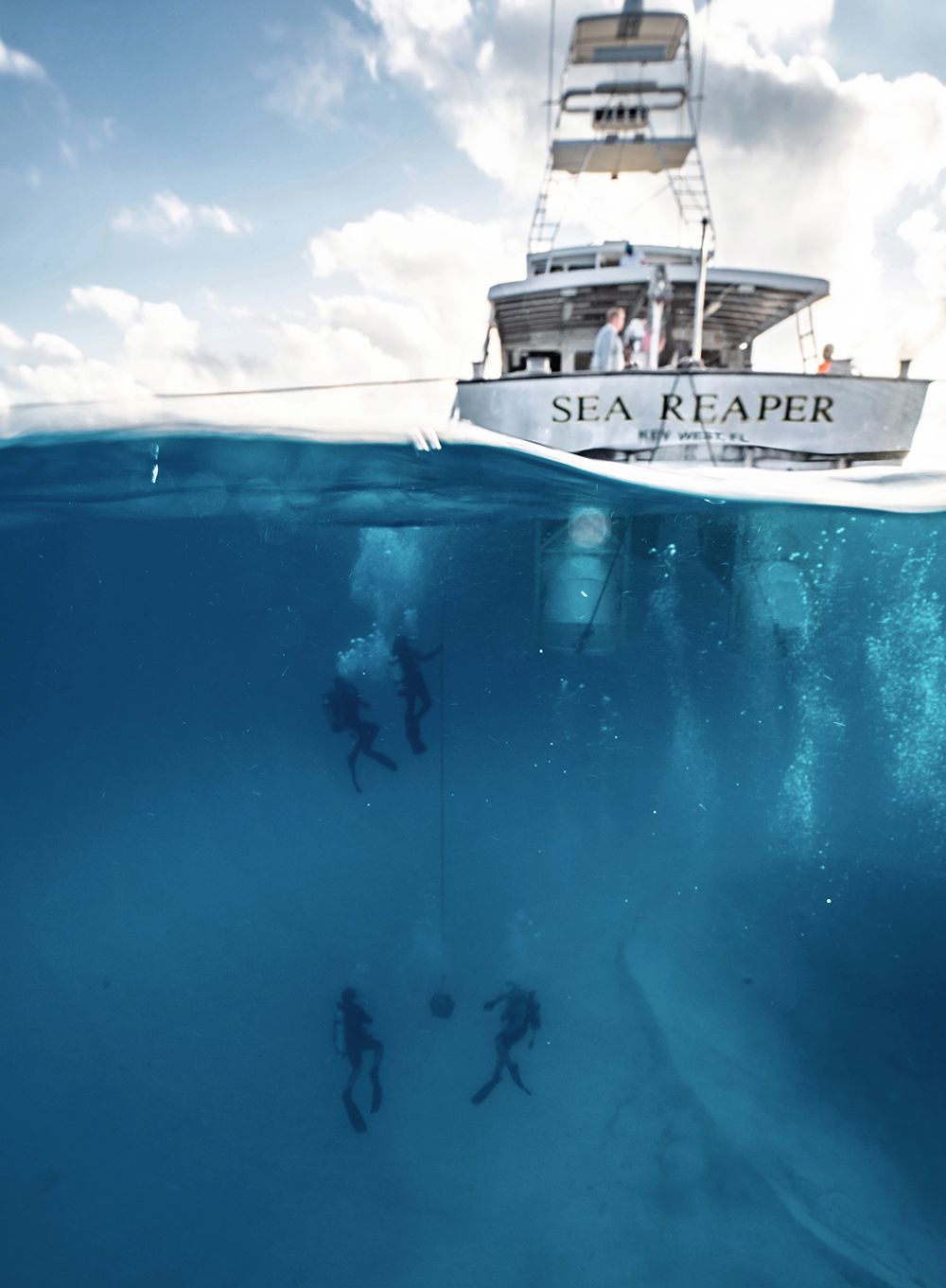

The salvage began. The bright, glassy sea hid untold riches – but where? Chunks of the Maravillas had been scattered over what was thought to be an area of several square kilometres, most of which had been untouched by earlier salvage attempts. Allen hired Dan Porter, a shipwreck recovery specialist who oversaw the search for fruitful dive sites.

Porter has a knack for the task of mathematically modelling where debris may have ended up, a skill that, given the limitations of marine metal detection – magnetometers, which detect magnetic materials, have a range of only a few metres and must be towed beneath a boat – turned out to be extremely useful.

Magnetometers have other limitations, such as a tendency to be set off by lobster condos. These are structures left by fishermen for lobsters to make into a home (from which they will one day be harvested).

The lobster condos make for “one heck of a signature” on the magnetometer, Porter told Wreckwatch magazine, but the team’s high-resolution side sonar helps them distinguish between condo and cargo. “That saves a lot of time and sweat off the search, not needing to do dive reconnaissance,” Porter says.

CHAD BAGWELL - ALLEN EXPLORATIONDiving to the wreck is done by scuba or in a three-person sub. Allen has 1,800 hours of “bottom time”

CHAD BAGWELL - ALLEN EXPLORATIONDiving to the wreck is done by scuba or in a three-person sub. Allen has 1,800 hours of “bottom time”

Diving, however, remains fundamental to the endeavour. Once a spot is identified, it is humans, in these relatively shallow depths of around 12 metres, who are best equipped to search for treasure in the sand.

The Allens are often among the divers; Carl estimates that he has reached 1,800 hours of “bottom time”, as time spent diving is known, over the past five years. Allen has found coins and a few emeralds, he says, and has been present at even bigger finds.

“It is special to hear people scream through a regulator and see them holding a gold chain or a big emerald in their hand, or a gold locket, or even some of the simple stuff. I mean, I get excited by pottery shards and Chinese porcelain. I love finding tobacco pipes. One of the things we’re discovering is really what it was like to live on the ship.”

In moments of celebration, Allen always urges calm. “The last time somebody touched that was almost 400 years ago,” he says. “There’s no need to go crazy. There’s no need to go flying to the surface. Take your time. Enjoy that moment.”

TREASURE HUNTING KIT

Tools that the AllenX team

finds invaluable

Side-scan sonar which creates an image of the sea floor.

Magnetometer: this device, towed beneath a vessel, can detect metal.

Diving gear: mask, fins, tank, dive watch and underwater metal detector.

Triton 3300/3 submersible (right) which can take people down to view the wreck without diving gear.

NICK VEROLA - TRITON SUBMARINES - ALLEN EXPLORATION

NICK VEROLA - TRITON SUBMARINES - ALLEN EXPLORATION

But there have been many finds worth celebrating: not only the exquisite golden filigree chain, which weighs almost a kilogram and would have been on its way to an exceptionally wealthy Spaniard, but also two golden pendants featuring Santiago crosses.

In delicate gold casing, one of these pendants houses a large emerald surrounded by 12 smaller emeralds that represent the Apostles; another contains an Indian bezoar stone, which was thought to have healing properties.

The 10,000 artefacts recovered by AllenX from the Maravillas include several silver bars, 3,000 silver coins, 828 lead musket balls and more than 100 additional emeralds and amethysts. Once dug out of the seabed, the artefacts are brought to the surface and put in plastic boxes, still in water. Then they are delivered to the museum.

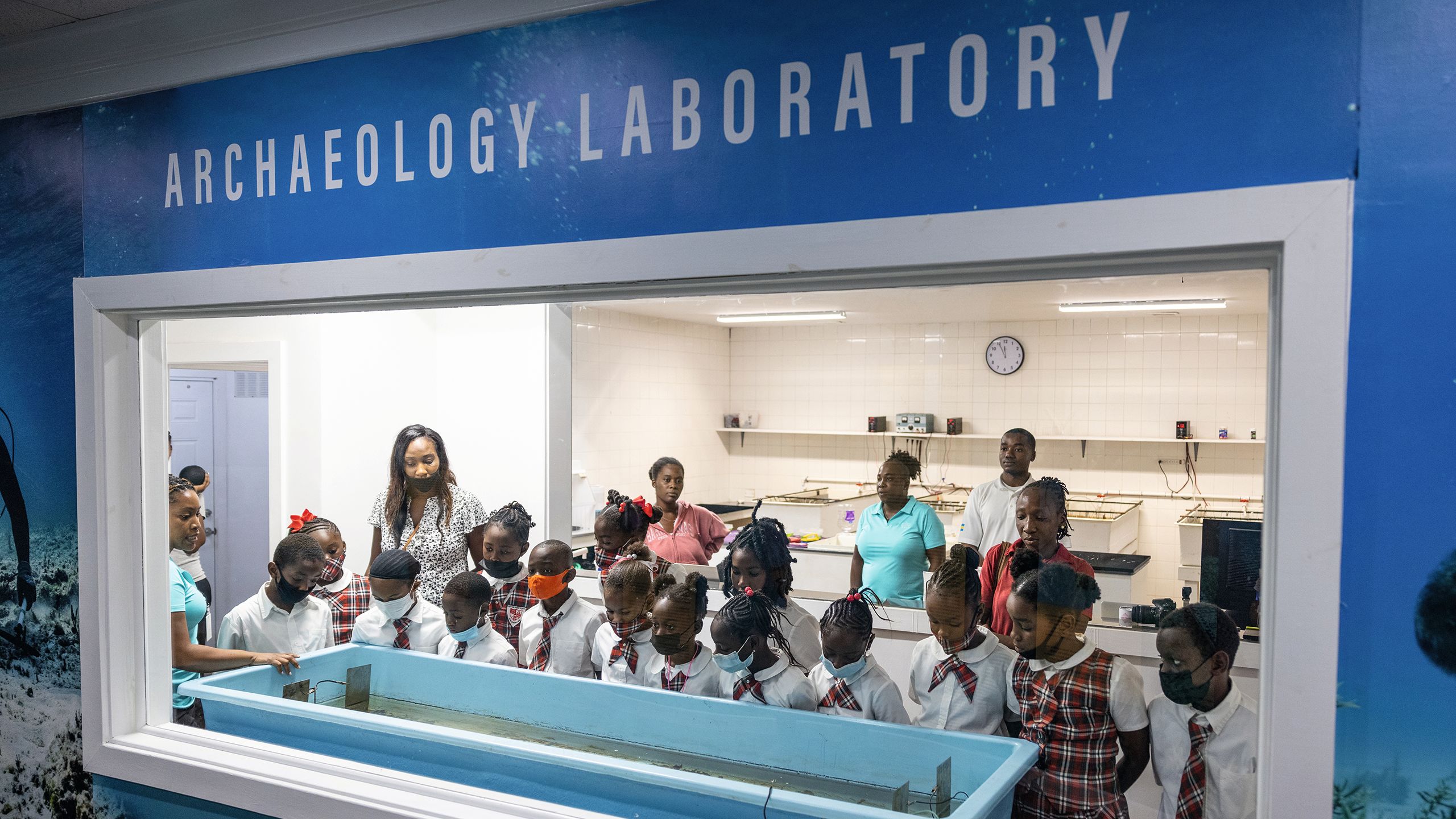

The museum opened in August 2022, and is sited in Freeport, Grand Bahama. I visited late last year, towards the end of hurricane season, and was bewitched by many of the finds: oddly affecting little things like cutlery, so redolent of the day-to-day activity that we have in common with the doomed passengers, and also the middle-ranking finery, such as the beautifully engraved silver dishes, and the jewellery, all the more startling for its smallness and delicacy.

Towards the end of walking around the exhibits, I reached a wall-sized window that looked on to a laboratory. Dr Michael Pateman, the museum’s director, showed me round. It’s here that the artefacts, which are generally encrusted with salt, are processed.

They are put into vats containing water infused with sodium bicarbonate, run through with a continuous electric current. (Stick your finger in and you’ll get a mild shock.)

This current draws out the salt, very slowly cleaning the artefacts; they typically spend months in the vats, even years. I saw a cannonball and a pair of pliers, with bubbles slowly rising from each.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

“It was a hobby that's turning into a very legitimate business”

Pateman also showed me the museum’s library, which includes Robert Marx’s large array of books on shipwrecks. Here the museum’s team teaches Bahamian schoolchildren about the collection. Sometimes they take them to the lab.

“We teach them how to clean coins using modern pennies,” Pateman says. “We have pottery that we’ve broken that they put back together. And then we also have pottery that they clean. It’s really about educating kids on what’s here in the Bahamas and their maritime heritage.”

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONThe Bahamas Maritime Museum helps educate local schoolchildren on the rich history of the waters surrounding them

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATIONThe Bahamas Maritime Museum helps educate local schoolchildren on the rich history of the waters surrounding them

Much of Pateman’s academic work has been on the Lucayans – the indigenous Bahamians of whom little trace remains – and on the transatlantic slave trade. Treasure hunting has been likened to the exploitative colonialism of yore, but Pateman views the AllenX salvage operation as unlike those that preceded it.

“A lot of people have the wrong perception of the project,” he says, “and that’s something we’ve been educating them on.” It helps that the Allens are known for their local philanthropy. After Hurricane Dorian ravaged the Bahamas in 2019, the Allens mucked in with the clean-up, arranged the delivery of supplies and donated $500,000 to relief efforts. AllenX and the museum have created dozens of local jobs.

ALLEN EXPLORATION

ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

The Allens arranged the delivery of supplies and donated $500,000 to relief efforts following Hurricane Dorian (left); AllenX and the museum have created dozens of local jobs (right)

Some of the shipments to the museum, says Pateman, are less exciting than others. “We have a lot of ceramics and musket balls.” But other artefacts more than compensate, whether they are an intact bottle, a piece of jewellery or, as on one occasion, a sword that turned out, on being cleaned, to have somebody’s name on it. “We were actually able to research and find out a bit more about this person,” Pateman says.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

And perhaps some even more exciting shipments might arrive at the museum lab sooner rather than later. Allen tells me that he and the crew are currently following a trail of plates, utensils and tobacco that their modelling suggests might lead to a “mother lode” of goodness knows what.

WHAT LAWS GOVERN MARITIME

TREASURE HUNTING?

Shipwrecks tend not to be free-for-alls. If they lie within a country’s territorial sea, which extends up to 12 nautical miles from its coastline, then it is governed by whatever laws that country has over salvage operations.

The US’s Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1988 lists shipwrecks that are effectively owned by the government. The Law of Finds, however, grants some rights to salvagers of ships not mentioned by the Act. States have their own regulations and permits. Elsewhere, Spain is notably stringent about salvage operations, as is the Bahamas.

Internationally, there is a little more room for manoeuvre. A UNESCO convention – the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage – prohibits commercial exploitation of underwater heritage.

This can be enforced by the country to which a salvage vessel is flagged. Many wrecks already have claims on them, whether claims from nation states or from the people who sailed in those ships.

Shipwrecks tend not to be free-for-alls. If they lie within a country’s territorial sea, which extends up to 12 nautical miles from its coastline, then it is governed by whatever laws that country has over salvage operations. The US’s Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1988 lists shipwrecks that are effectively owned by the government.

The Law of Finds, however, grants some rights to salvagers of ships not mentioned by the Act. States have their own regulations and permits. Elsewhere, Spain is notably stringent about salvage operations, as is the Bahamas.

Internationally, there is a little more room for manoeuvre. A UNESCO convention – the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage – prohibits commercial exploitation of underwater heritage.

This can be enforced by the country to which a salvage vessel is flagged. Many wrecks already have claims on them, whether claims from nation states or from the people who sailed in those ships.

Of the value of the wealth scattered across the seabed, Allen says: “The total value is unknown, because of the contraband. But I believe it’s a minimum of a couple of billion [dollars’ worth of money and artefacts], all the way up to tens of billions.”

As a yardstick, the Atocha haul – that’s the one unearthed by Mel Fisher, near Florida – was valued at around $400 million. There are hundreds more wrecks in the Bahamas and the surrounding area, many of which were ships that were of considerable value to colonial powers.

MATTHEW LOWE - ALLEN EXPLORATION

MATTHEW LOWE - ALLEN EXPLORATION

AllenX has loosely staked out 19 wrecks in total. “I think now that I can keep this going,” says Allen. “Allen Exploration was a hobby that’s turning into a very legitimate business.”

One model by which licensed companies can profit would involve governments keeping any major artefact while the company gets to sell the majority of the coins they unearth – although Allen Exploration has not received money from the Bahamian government for the treasure in the museum.

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

BRENDAN CHAVEZ - ALLEN EXPLORATION

Allen, Gigi and Dr Michael Pateman (far left) open the museum

Allen is not the only fabulously wealthy individual to have turned their focus towards the risky business of treasure hunting. Last year journalists unmasked the mystery financier behind several lucrative deep-sea salvage operations.

Anthony Clake, a hedge fund executive, seems to have got into the business in order to make money, only for his financial investment to become an intellectual one. “I don’t do it for a living,” he told Bloomberg. “I find it interesting to use technology to solve problems under the sea.” (“It’s fucking treasure fever,” said a former colleague.)

Irrespective of the business opportunity, Allen insists that his work isn’t about the money. “It’s the adrenaline rush,” he says. “It’s proving people wrong. You know, it’s... I don’t know, it’s just sort of a... I don’t know what people do in life who don’t treasure hunt!”

First published in the May 2024 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.