ON

BOARD

WITH

Thibaud Epstein

On board Kudanil Explorer

Sam Fortescue charts a life of daring choices - and a mission to reinvent a 50-year-old towing vessel as a superyacht

BIOGRAPHY

Thibaud Epstein, born in 1981, studied at Paris Descartes University and UTS Sydney before embarking on a career that blended law, finance, and entrepreneurship. Today, he lives in Bali with his wife Anita and their child Leo, dividing his time between the island and the Kudanil Explorer

Thibaud Epstein’s vivid description of wading upriver for 40 minutes to find a waterfall in West Papua that paints the best picture. That and the urgent necessity to placate a wellarmed, recently displaced gathering of villagers preparing to stand their ground on the beach. “We assured them we didn’t want their land and were able to share our supplies with them. In return, they showed us the waterfall,” he says.

Epstein is sketching out the many reasons why he fell in love with South East Asia and came to found a charter business on a 50-year-old towing vessel. His case is compelling: “Indonesia has a sense of hospitality that you find in few places in the world. There is no better playground. It makes an experience that is second to none.”

JACK JOHNS

JACK JOHNS

As he talks it becomes clear that the usual lines between ownership and business are blurred; that he loves his yacht Kudanil Explorer as much for the roar of her 50-year-old engines as for the adventures she enables.

“The whole hull is so spacious, you can walk around the engines,” he enthuses. “It has a vintage look, because the engines are older than me. That’s magical as well. I still skipper the boat, deciding where we go and where we anchor, though the crew is very competent now. I’m aiming not to be a yacht owner trying to recoup some of the cost by chartering.”

JACK JOHNS

JACK JOHNS

It was late in the last century when this restless young Frenchman ditched the limitations of his native Paris and headed almost as far away as it’s possible to go.

“I went to Australia, and ended up staying for six or seven years,” he says. “I did an MBA there and became a permanent resident. I lived in Bondi Beach, so I was surfing before work and going in with sandy feet – it’s just 30 minutes from the city. Paris had almost felt like a museum; there was something suffocating about it. Everything in Australia was fresh. It had an energy you couldn’t find in many places.”

With much of his family still in France, Epstein would travel back and forth periodically, stopping over in Singapore, where his uncle ran a small fleet of support and survey vessels. Epstein was fascinated and would help out during his stays, which become longer and more frequent.

“I would start spending more and more time with my uncle when I stopped over,” he remembers. “I thought all his mariners looked like pirates, with bandanas in the hair, going off exploring. It looked like a life of adventure. I’m extremely entrepreneurial and I loved it.”

JACK JOHNSExpeditions include surfing and waterfall hikes in little-visited parts of Indonesia

JACK JOHNSExpeditions include surfing and waterfall hikes in little-visited parts of Indonesia

Although he had studied law in France and Australia, he soon found himself rolling up his sleeves and joining the boat business at his uncle’s invitation. The older man had a similarly entrepreneurial spirit, having started out with French trading and shipping conglomerate Dreyfus.

His leaving package provided the funds to establish his own little shipping empire, which he thought he could run better. It was a different challenge every day, from hiring staff to negotiating contracts, and Epstein found he was good at it. “We were such a small team – everything I did, you were parachuted in and had to find your way,” he says.

“All my uncle's mariners looked like pirates, with bandanas, going off exploring. It looked like a life of adventure”

“I was a pinball. We were developing this business in Jakarta and we also had boats in Thailand, so I was between the two. We had won contracts in Indonesia, and at the time you needed a local company to run an Indonesian-flagged vessel, so I spent a lot of time there.

“We turned our hands to many different types of work: oil platform maintenance, diving, surveying, platform commissioning with Schlumberger and Halliburton, towing and rescue.

. Kudanil Explorer

. Kudanil Explorer

“We were very good at it and one thing led to another until 2016/17, when the price of oil crashed. Contracts came to an end and we sold all our assets in the oil industry in two weeks – I mean, very quickly.

“I’m not sure why, but we kept one boat that had been built as a supply vessel and used to tow tankers out of trouble.” Here, he pauses, eyes fixed in the distance, then chuckles drily to himself. “Soon after that, the price of oil went back up and tourism crashed with Covid – so the best advice is to do the opposite of whatever I do next!”

It’s fair to say that he can afford some gentle self-mockery. At its height before oil prices dived below $20 a barrel, Kuda Nil Marine Services was turning over around $10 million per year, owned three ships and had around 40 crew on the payroll, with seven office workers in Jakarta and Singapore. Profit margins were good, Epstein admits, naming a figure well north of 50 per cent.

It gave him a decent cushion for considering the next move. The sea loomed large in his thoughts, as it had done for most of his life. From childhood holidays spent in the sailing playground of southern Brittany, a family home in the spa town of Bénodet and numerous weeks cruising Beneteau First sailing boats with his father, the association between salt water and fun was hardwired in.

Even his years at a Jesuit boarding school in landlocked Reims couldn’t shake it. “I was a bit of a turbulent kid at times,” he admits. “It was just kids being kids, but I fought with my older brother sometimes and for my mum it was tough. Those were different times, though. I smoked a joint and Mum thought I was becoming a junkie!

“I thought it was great when she sent me to boarding school – suddenly your parents are out of the picture and you were on your own boat. The school followed self-discipline, and the concept was kind of fun. The older kids would discipline the younger kids, and we were all grouped by centres of interest.”

JACK JOHNSEpstein describes the refit process as that of fitting a boutique hotel inside the hull of a trusty old commercial vessel

JACK JOHNSEpstein describes the refit process as that of fitting a boutique hotel inside the hull of a trusty old commercial vessel

Perhaps this was the crucible for Epstein’s entrepreneurship. If so, it was alloyed with a strong sense of structure from following his father’s lead by training in the law.

“The law degree has been helpful – it gives structure; it’s a way to look for solutions,” Epstein says. “I don’t use it every day, where I’m more focused on trying to keep the deck clean or work in the engine room. The MBA was extremely useful, though. It gives you a language and framework of how the world works that is extremely solid. It’s a very good map.”

Outdoor space is copious, as you would want in such climes

It all became more relevant as he mulled that next step, speaking to others in the charter industry before deciding to turn Kudanil into a charter boat.

The first step was a multimillion-dollar refit to convert her from a commercial vessel with 32 berths into something suited to high-end tourism. Epstein recruited a team to help him, starting with Simon Jupe, a British naval architect with experience of ship conversions.

JACK JOHNSThe ethos is to encourage charter guests to get the most out of their extraordinary remote environment

JACK JOHNSThe ethos is to encourage charter guests to get the most out of their extraordinary remote environment

He still needed a yard to carry out the work and, rather than choosing a local business, he formed a partnership with another French contact. Bertrand d’Alencon had just sold the Agmar shipyard in Brittany and was looking for a new project. “We kind of created our own yard at Subic Bay in the Philippines – hired people and bought our own equipment,” Epstein says.

The existing machinery may have stayed (“I can walk you through the engine room bit by bit – I operated her in the old days”), but the refit was more than simple window dressing. Epstein had the steel superstructure extended aft to create space for another six cabins at upper deck level. With the two existing cabins, accommodation was extended to 16 people in eight similar 30-square-metre cabins, each with its own bathroom and balcony. Hotel systems were upgraded, from air con to water treatment, and the old towing winches and some capstans were removed.

JACK JOHNSKudanil has a large selection of tenders and toys, a dive shop equipped with Nitrox and even jet skis, although these are mainly used for finding the best surf spot

JACK JOHNSKudanil has a large selection of tenders and toys, a dive shop equipped with Nitrox and even jet skis, although these are mainly used for finding the best surf spot

Then we sailed to Semarang in central Java,” says Epstein. “It’s the capital of wood processing in Indonesia, and we found a yard and a carpenter able to produce in enough quantity and with enough quality to build all the interior. We got in Alix Thomsen to design it. She has done boutique hotels in Paris mostly, so we got her to travel throughout Indonesia to get inspired and do something timeless with it.”

The main deck below has been converted to offer an indoor saloon, library lounge, wine store and spa, while there is a smaller upper saloon on the top deck. Outdoor space is copious, as you would want in such climes. Most of the action, from long dining tables to comfy sofa groups and a bar, is on the upper deck, under a canvas bimini. But there is also a spa pool and loungers at the foot of the mast, on a half-deck dubbed Monkey Island.

For all that Epstein has done to create a luxurious environment for guests, Kudanil is not really intended to deliver the sort of pampering that some might expect for $175,000 per week. “We have a jacuzzi, cinema, gym and lots of inflatables,” Epstein admits. “But if we use all this, we’re not really doing our job. If a guest is in the gym every morning, it’s because they’re not on an SUP! I try to use the destination as the playground.”

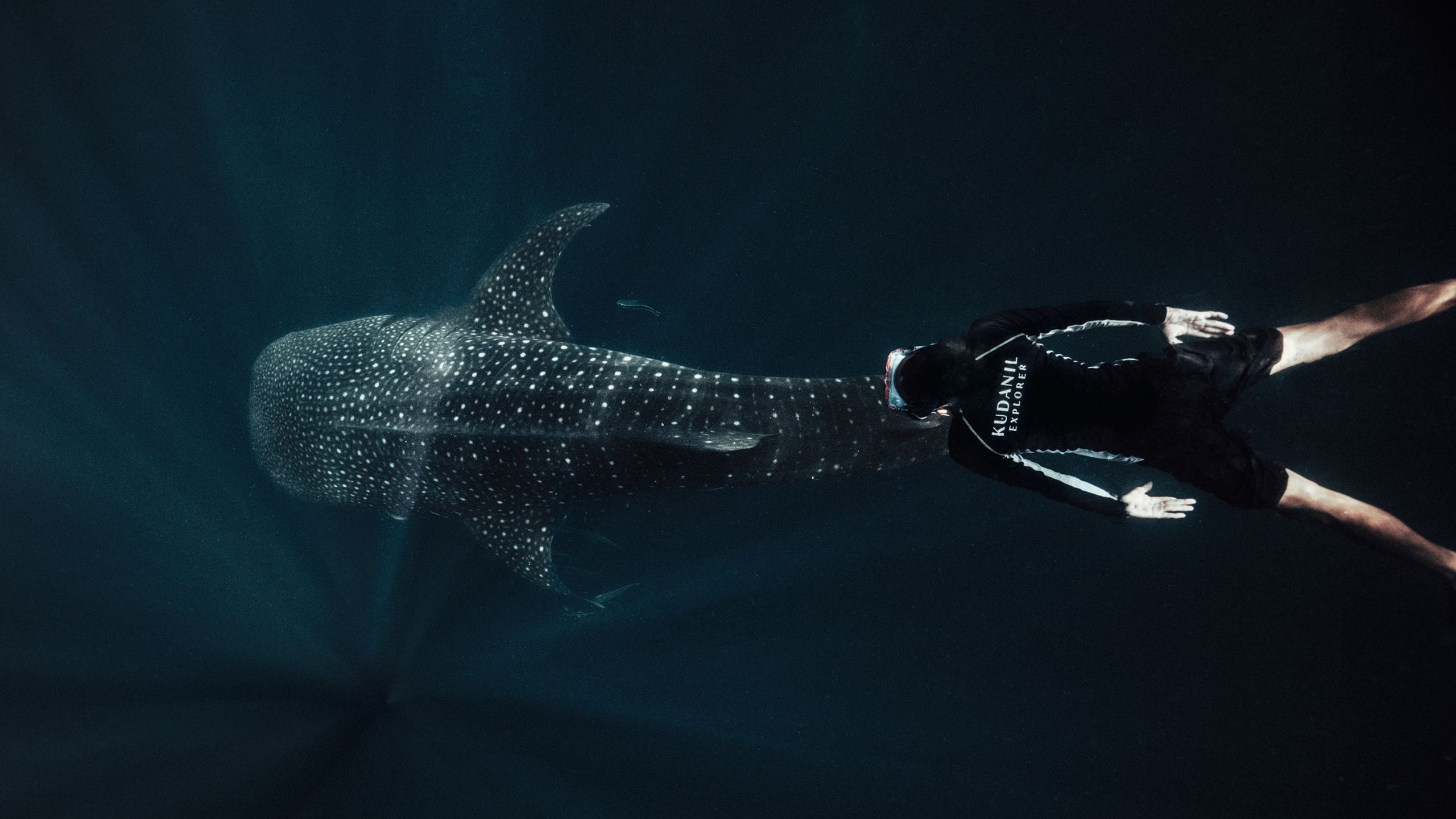

Kudanil has remained true to her explorer roots, with the aim of introducing guests to the enchanted waters between the Pacific and the Indian Oceans. Over years of operating in the region, Epstein and his captain have identified a treasure trove of remote surfing spots, dive sites and inland hikes that aren’t on anyone else’s itinerary, from the ring of fire and the relics of the colonial spice trade, to the wilderness of Papua.

The wild scenery combined with local hospitality and a lifestyle inspired by his Bondi days kept Epstein’s boat chartered for an impressive 120 days last year (Pelorus is the central agent for charter). He hopes to top that in 2025 and is already thinking about expanding the business with another yacht. “I’m an operator at heart, not a marketeer, and I love boats,” he says. “The reputation we’re starting to build in our industry depends essentially on that.

First published in the September 2025 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.