AIR, LAND AND SEA

How Marala and Evaine rekindled the golden age of yacht racing

When Marala’s owners went in search of her 12 Metre Class sistership Evaine, they discovered a rich racing history centred around two great aviation rivals. Daniel Pembrey tells the tale

“She should race,” says the husband of a Hong Kong-based couple who just acquired Evaine, the almost-mythic, 12 Metre Class 1936 21-metre sailing yacht once owned by aviation tycoon Sir Richard Fairey. Her restoration is now underway at the Robbe & Berking yard in Flensburg, Germany, and it comes in the wake of the same intrepid couple purchasing Marala, the 59-metre Camper & Nicholsons superyacht built in 1931 and recently restored by Pendennis in Cornwall.

Marala (formerly Evadne) also belonged to Fairey. “Marala was the mothership for his racing activities,” explains the husband. “We’re still piecing together exactly how Marala supported Evaine, but reuniting them for the first time in 70-some years already feels remarkable.” From her destroyer bow to her cruiser stern, this six-cabin superyacht made a worthy mothership, combining true functionality with great comfort.

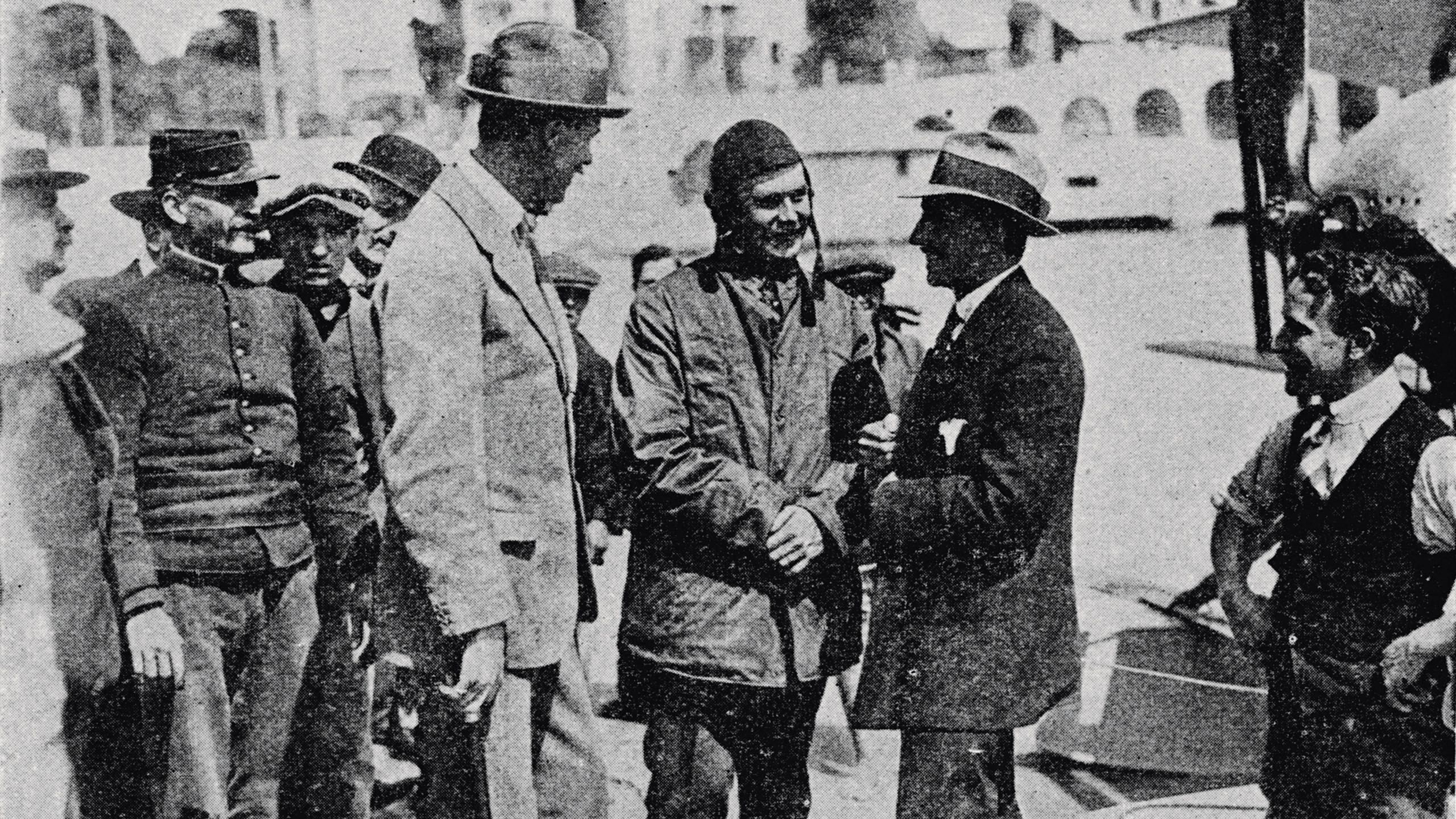

PPL LIMITED - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOFairey at the helm of the J Class Shamrock V, which had been previously owned by Sir Thomas Sopwith

PPL LIMITED - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOFairey at the helm of the J Class Shamrock V, which had been previously owned by Sir Thomas Sopwith

Working with Marala’s versatile captain, Chris (Lawrie) Lawrence, the couple had previously attempted to track down Flica, another of Fairey’s hallowed 12 Metre Rule sailing yachts – also known as Twelves. Flica’s whereabouts remain tantalisingly vague, however Evaine proved easier to locate, sitting as she was in a dim resiny-smelling shed in Kiel, not 100 kilometres from Robbe & Berking’s yard.

MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARYThe 12 Metre Flica

MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARYThe 12 Metre Flica

Working with Marala’s versatile captain, Chris (Lawrie) Lawrence, the couple had previously attempted to track down Flica, another of Fairey’s hallowed 12 Metre Rule sailing yachts – also known as Twelves. Flica’s whereabouts remain tantalisingly vague, however Evaine proved easier to locate, sitting as she was in a dim resiny-smelling shed in Kiel, not 100 kilometres from Robbe & Berking’s yard.

The yacht-racing scene these yachts formed part of almost a century ago was an enthralling world. It combined big characters and epic personal rivalries, yacht designers of the highest order, revered classes (both larger J Class yachts and Twelves), routinely thrilling battles out on the water in English coastal regattas, plus the fiercest, most famous contest of them all: the America’s Cup.

One rivalry stood apart for its sheer dynamism, however. It also involves Sir Richard Fairey, and unravelling it provides a uniquely fascinating window into this realm...

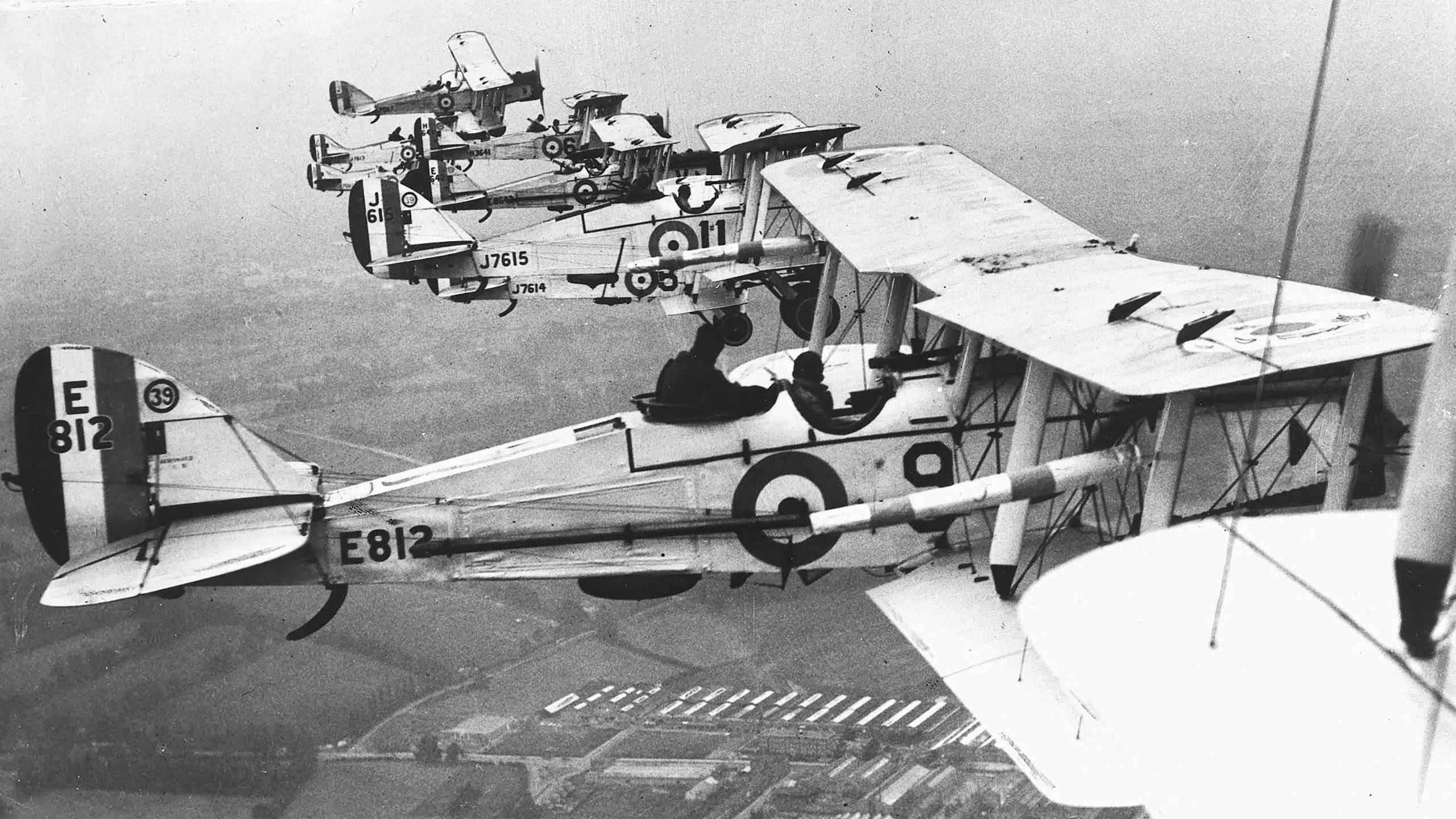

Fairey and fellow Briton Sir Thomas Sopwith were aviator rivals first, each responsible for planes proving pivotal in both world wars. Fairey built the Swordfish torpedo bomber that hit the rudder of the Bismarck battleship, plus the postwar Delta 2 that broke the 1,000mph speed barrier, its delta wings and drop-nose helping shape Concorde.

Sopwith started out making biplanes, notably the celebrated Camel for the First World War, before leading the Hawker Siddeley group into the jump-jet era with its astonishing VTOL Harrier. Still, their rivalry was arguably greatest in the gleaming seas off the south coast of England on the tense eve of the Second World War, racing achingly beautiful Twelves, balloon jibs flying, salt air filling the nostrils and the sound of rushing water filling their ears.

PAUL THOMPSON - FPG GETTY IMAGESSir Thomas Sopwith was a pioneer of the British aviation scene

PAUL THOMPSON - FPG GETTY IMAGESSir Thomas Sopwith was a pioneer of the British aviation scene

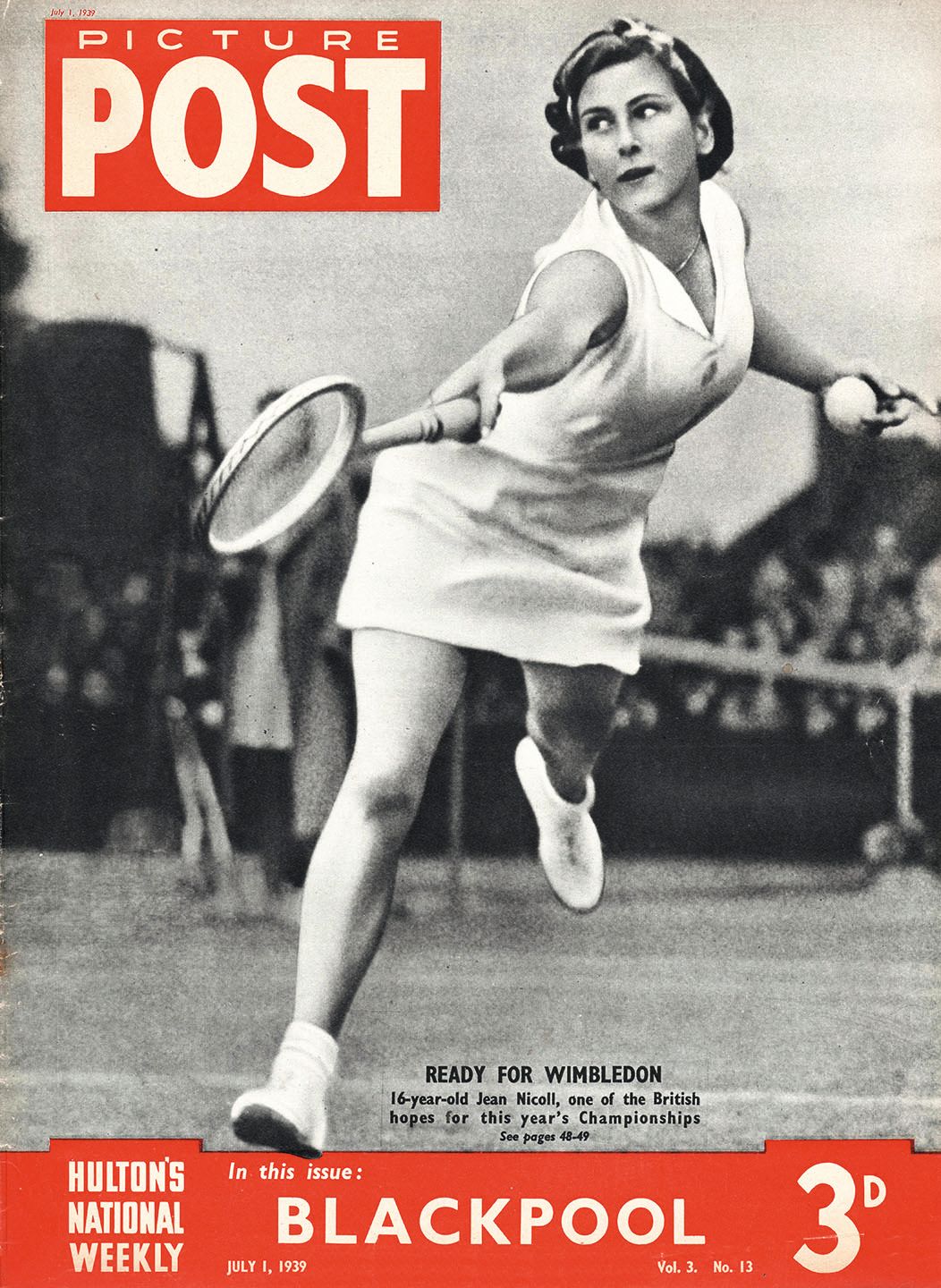

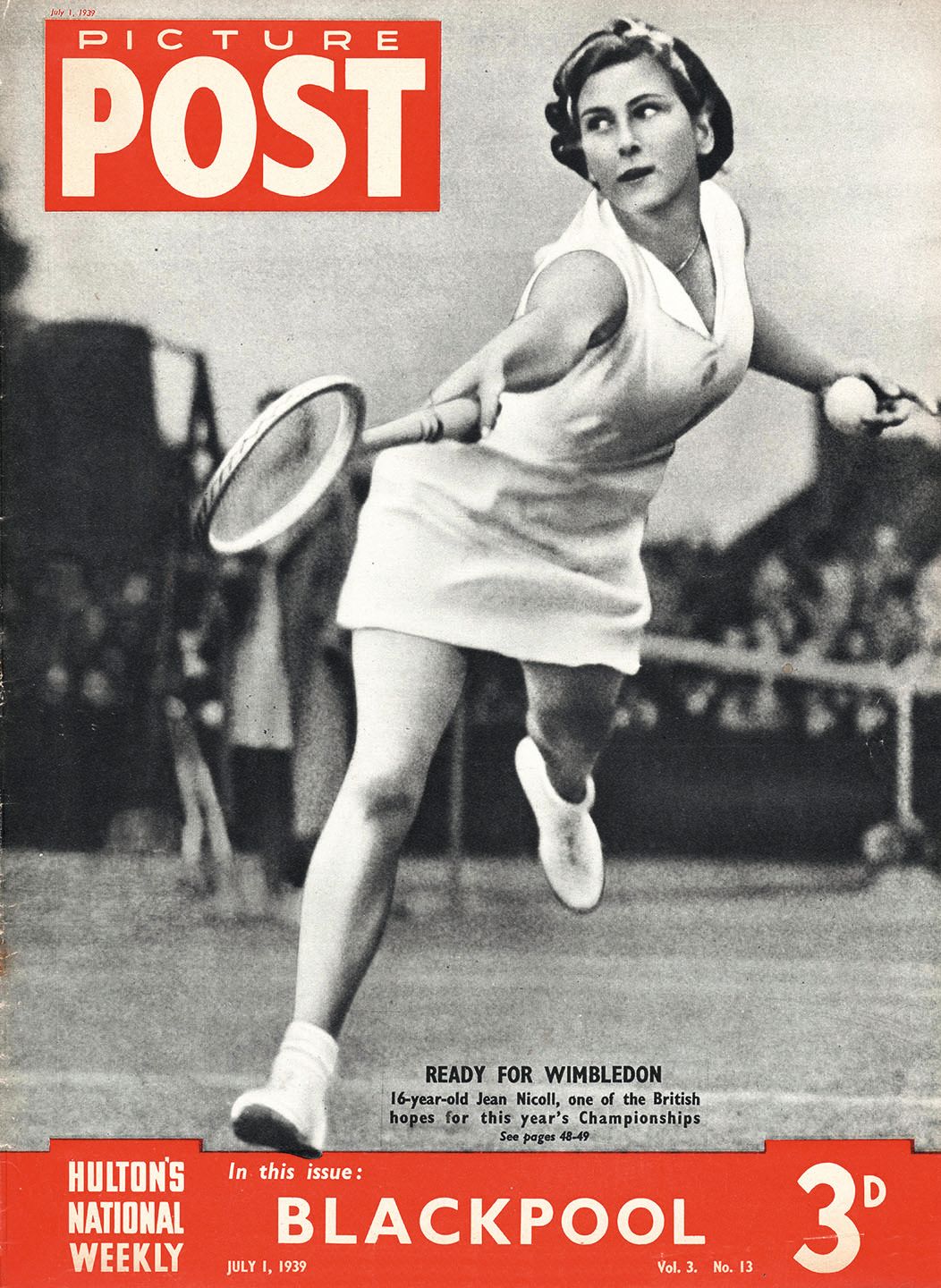

On 1 July 1939, Picture Post (a popular British magazine back then) ran a six-page feature, Yacht-Racing. It brought alive the Royal Harwich Yacht Club’s regatta of the day. “Watch Sopwith!” heard John Scott Hughes, the features writer, who was on board Fairey’s Evaine.

“What a slapping and hissing of spray along our slanting decks!” he marvelled. “Over and over she lists as [helmsman] Garnham gives her a few spokes of the wheel, while high overhead towers Tomahawk’s dazzling sail [Tomahawk was the name of Sopwith’s own Twelve]. There is not a foot – a bare six inches – from rail to rail. How is it they don’t crash together!

JOHN FROST NEWSPAPERS - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

JOHN FROST NEWSPAPERS - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Picture Post covered a regatta where Fairey and Sopwith raced

MARY EVANS - BRANDSTAETTER IMAGES

MARY EVANS - BRANDSTAETTER IMAGES

Fairey was also an aircraft manufacturer...

THE PRINT COLLECTOR - GETTY IMAGES

THE PRINT COLLECTOR - GETTY IMAGES

... and built the Swordfish torpedo bomber

Picture Post covered a regatta where Fairey and Sopwith raced. Fairey was also an aircraft manufacturer and built the Swordfish torpedo bomber

Then: “We’ve Got Her!” cries a photo caption. “On the starboard tack, and therefore having right of way, Evaine crosses ahead of her rival Tomahawk, whom she will now have safely under her weather,” the photo caption goes on. “In the final order Evaine was second, and Mr T. O. M. Sopwith’s Tomahawk third, with Mr V. W. MacAndrew’s Trivia the winner. Vim, the American yacht, got round the course first but was disqualified.” She rounded the wrong buoy.

“Airmen, it seems, make good seamen. They know by instinct the feel of the helm to the hand”

“Tiny” Fairey stood 201 centimetres tall and was, by all accounts, a benevolent tyrant. Quick to anger, he ruled his business affairs with an iron will that served them well. He’d come from humble origins: “I remember him saying through gritted teeth, ‘I swore I would never be poor again’,” his daughter recalled in 2017.

Fairey acquired his first Twelve, Modesty, in 1927. Air flows and stresses were second nature to him and he set up test facilities at his Hayes aircraft factory, exploring how reshaping the hull and rerigging her might gain speed. He used (allegedly) the world’s first low speed wind tunnel for racing yacht design, in addition to hydrodynamic tank testing.

“Having drafted in the technical staff required to rebuild and maintain Modesty,” wrote Adrian Smith in his biography, The Man Who Built the Swordfish, “the fledgling helmsman acquired a crew of canny old salts and fit young yachtsmen.”

THE ROYAL AERONAUTICAL SOCIETY (NATIONAL AEROSPACE LIBRARY) - MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY Sir Richard Fairey

THE ROYAL AERONAUTICAL SOCIETY (NATIONAL AEROSPACE LIBRARY) - MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY Sir Richard Fairey

The key man remained Fairey. “Airmen, it seems, make good seamen, and particularly in the finer arts of racing,” observed Yachting World magazine in November 1933. It deemed both aviators suitable for contesting the America’s Cup.

“They know by instinct the feel of the helm to the hand; they readily realise the effect of the wind on the sails, and their minds react to the sensitive observation of the trim of the sheets.”

Fairey acquired his first Twelve, Modesty, in 1927. Air flows and stresses were second nature to him and he set up test facilities at his Hayes aircraft factory, exploring how reshaping the hull and rerigging her might gain speed. He used (allegedly) the world’s first low speed wind tunnel for racing yacht design, in addition to hydrodynamic tank testing.

“Having drafted in the technical staff required to rebuild and maintain Modesty,” wrote Adrian Smith in his biography, The Man Who Built the Swordfish, “the fledgling helmsman acquired a crew of canny old salts and fit young yachtsmen.”

The key man remained Fairey. “Airmen, it seems, make good seamen, and particularly in the finer arts of racing,” observed Yachting World magazine in November 1933. It deemed both aviators suitable for contesting the America’s Cup.

“They know by instinct the feel of the helm to the hand; they readily realise the effect of the wind on the sails, and their minds react to the sensitive observation of the trim of the sheets.”

BETTMANN - GETTY IMAGES

BETTMANN - GETTY IMAGES

The America’s Cup would frustrate both airmen, but that didn’t stop Fairey from continually refining his Twelves . He commissioned state-of-the-art Flica from Charles Nicholson in 1929 and she dominated British and European 12 Metre racing from 1931 until the rule rating changed in 1933.

Yachting World reported that not only was Flica the best of the Twelves, but also Fairey was now Britain’s best helmsman. Still he wasn’t satisfied. Daily wind tunnel tests resulted in revisions to sail settings. Duralumin used in Fairey planes inspired lighter, sturdier spars. A quadrilateral jib counted among other innovations. Along the way, he found time to race in the Baltic, winning the Norwegian royal family’s Jubileums Regatta, using his superyacht Evadne as mothership.

Fairey bought Evaine from Charles Nicholson in 1936; there was just enough time to complete her for that year’s season. The yacht, named after the sister of Lancelot’s mother, Elaine, in Arthurian legend, was simply beautiful. Mahogany planking gracefully gave way to cedar used for all interior fittings. White topsides contrasted a green underwater body.

The following two years proved truly vintage ones for these Twelves. Due to declining health, Fairey passed the helm to Bob Garnham (starring in the Picture Post spread), and Vernon MacAndrew’s Trivia edged out Evaine as overall winner in both seasons, yet none of this lessened Fairey’s competitive zeal.

“Tommy” Sopwith hailed from a comfortable background, only with a tragic twist. In the summer of 1898, his father took him shooting on the Isle of Lismore in Scotland. They were in a boat when a gun lying across 10-year-old Tommy’s knees accidentally went off, killing his father. Whether or not there was a faulty safety catch is unclear. The spectre of how he’d let this happen would haunt him for the rest of his long life (he died aged 101).

Sopwith developed a deep-seated urge to achieve. The Schneider Trophy air race began in Monaco in 1913 as a prestige event for seaplane makers. Sopwith’s remarkable Tabloid biplane won it the following year, 1914, when he was 26.

DAILY MIRROR - DAILY MIRROR MIRRORPIXSopwith created the Camel biplane

DAILY MIRROR - DAILY MIRROR MIRRORPIXSopwith created the Camel biplane

During the First World War, the Sopwith Aviation Company’s Camel was the only plane able to shoot down dreaded Zeppelin bombers, conferring hero status on him and his business. Its sudden downsizing, required by the end of the war, effectively bankrupted the company, so Sopwith started over. To avoid confusion, he used the name of a friend, the gifted Australian test pilot Harry Hawker. The Hawker Siddeley group of companies would become half of Britain’s entire aviation industry.

Like Fairey, Sopwith applied advanced aviation techniques to yachting. Frank Murdoch, who managed production of the Hawker Hurricane (soon immortalised by the Battle of Britain), helped optimise Sopwith’s J Class yachts when challenging for the America’s Cup. Murdoch was schooled in England but born in Antwerp, with a grandfather who’d started a shipyard there. Now, in the 1930s, he found himself designing masts and rigging.

A. HUDSON - TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESThe launch of Sopwith’s Endeavour in April 1934 at Camper & Nicholsons

A. HUDSON - TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY - HULTON ARCHIVE - GETTY IMAGESThe launch of Sopwith’s Endeavour in April 1934 at Camper & Nicholsons

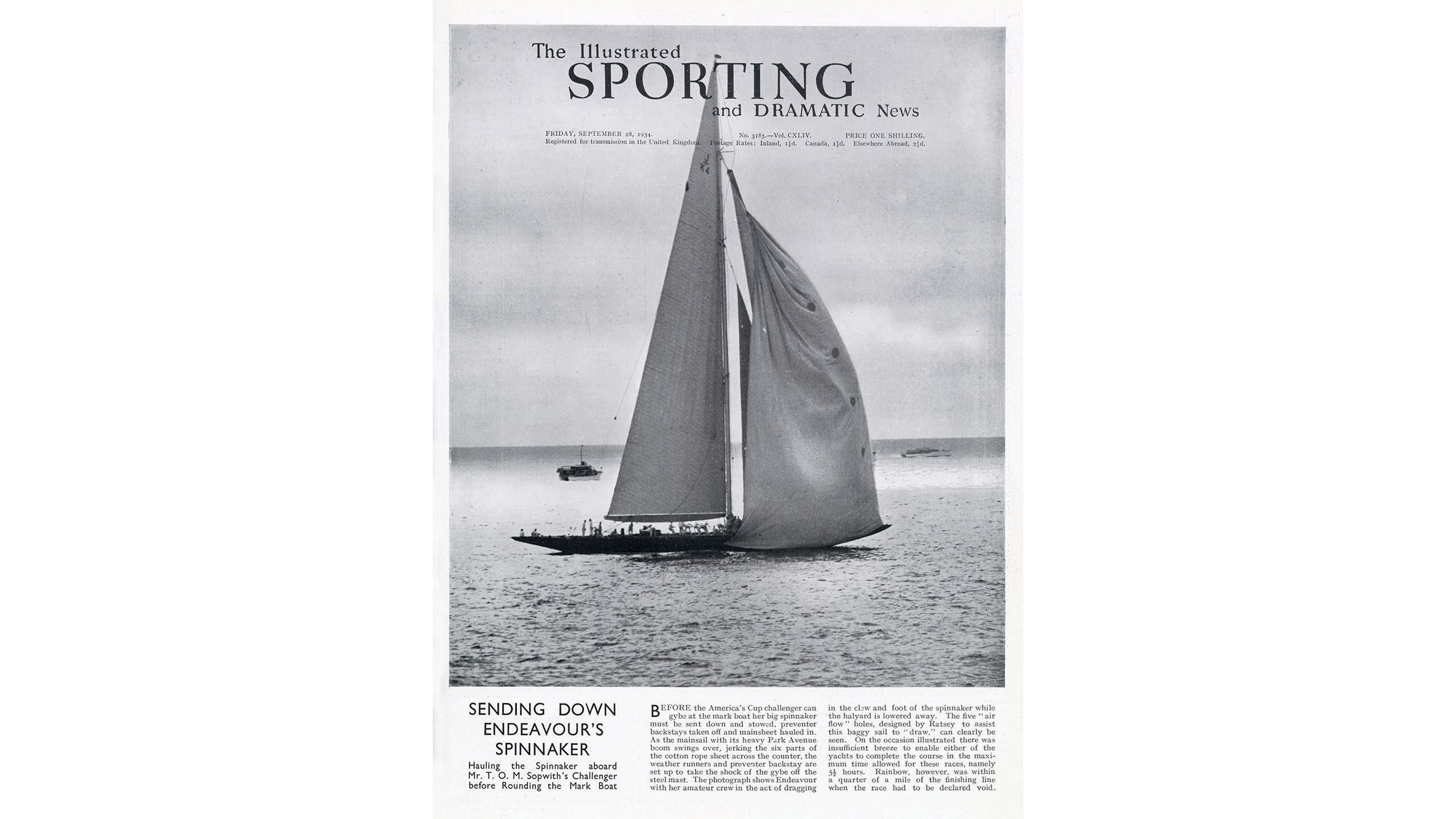

Sopwith’s J Class Endeavour was another Charles Nicholson masterpiece. Murdoch designed the advanced winches and welded steel mast promptly fitted. A wind vane perched on top of the mast fed readings to an indicator placed in front of the helmsman, and copious use was made of aircraft materials. She was a very fast, worthy challenger. The 1934 America’s Cup in Newport contested by Endeavour, with Rainbow as the American defender, might best be remembered for the churlish claims back in the UK, “Britannia rules the waves; America waives the rules!”

Sopwith was ahead by two races to one, when, “during the fourth race, the American boat persisted on a collision course and Sopwith was forced to turn away even though unquestionably Endeavour had right of way,” wrote Alan Bramson in his authorised Sopwith biography, Pure Luck.

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS LTD - MARY EVANS

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS LTD - MARY EVANS

Bramson did acknowledge that Sopwith had also parted ways, beforehand, with his professional crew over a pay dispute: an epic false economy? Regardless, Sopwith lost, and, when he next contested the Cup in 1937, his Endeavour II was beaten fair and square by the technically superior American defender. Sopwith had his own Camper & Nicholsons mothership superyacht, Philante (a portmanteau of his wife’s and son’s names, Phyllis and Thomas Edward).

Befitting a support vessel for these larger J Class yachts, she was 80 metres long featuring a workshop with an electric drill, lathe and milling machine, plus a steel-lined store for the sails and tackle for both his Js and Twelves. There were eight guest cabins and bathrooms, and eight “clothes rooms” (as distinct from wardrobes). Stabilisers were uncommon at the time so the nine- by eight-metre master cabin – featuring a huge four-poster bed – was complemented by a smaller “sea cabin” below decks, accessed from the master by a small staircase. Here, Sopwith could wedge into a bunk when the ship rolled uncomfortably.

The America’s Cup contests also resulted in a fierce rivalry between Sopwith and Harold Vanderbilt. The railroad executive and great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt had taken the helm of Rainbow in 1934 after those first two races (that put Sopwith’s Endeavour briefly ahead). While Sopwith might, meanwhile, have acquired a superyacht nearly twice the size of Vanderbilt’s Vara support yacht, it was Vanderbilt who beat him, again, in the 1937 America’s Cup. The scene was set for the 1939 regatta season, and the arrival in English waters of Vanderbilt’s Twelve, Vim.

This arrival was a recognition that Twelves had broken through as the dominant class for international yachting. Leading designers and yards, who’d previously created Js for the America’s Cup, focused on Twelves. Earlier in 1939, Nicholson built Tomahawk – one of the most beautiful of these smaller racers, her design an evolution of past Twelves with innovations including its “coffee grinder” winch and stainless-steel shrouds.

“Please don’t every let her go,

there is no second Vim and she needs you”

It’s tempting to wonder what would have become of Sopwith’s (and Fairey’s) racing exploits were it not for the war, but the reality is America firmly had the upper hand by then.

“Why not admit it?” asked John Scott Hughes, author of the 1939 Picture Post spread. “Our American friends are, by and large, the most accomplished yachtsmen in the world. That, really, is the entire explanation of why we have never recovered from them the America’s Cup, lost to them nearly 90 years ago.” American designers, crew and owners – influenced in no small part by Sopwith and Fairey’s aviation input – had won.

THE PRINT COLLECTOR - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOThe 12 Metres Vim and Tomahawk racing in 1939

THE PRINT COLLECTOR - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOThe 12 Metres Vim and Tomahawk racing in 1939

The America’s Cup contests also resulted in a fierce rivalry between Sopwith and Harold Vanderbilt. The railroad executive and greatgrandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt had taken the helm of Rainbow in 1934 after those first two races (that put Sopwith’s Endeavour briefly ahead). While Sopwith might, meanwhile, have acquired a superyacht nearly twice the size of Vanderbilt’s Vara support yacht, it was Vanderbilt who beat him, again, in the 1937 America’s Cup. The scene was set for the 1939 regatta season, and the arrival in English waters of Vanderbilt’s Twelve, Vim.

This arrival was a recognition that Twelves had broken through as the dominant class for international yachting. Leading designers and yards, who’d previously created Js for the America’s Cup, focused on Twelves. Earlier in 1939, Nicholson built Tomahawk – one of the most beautiful of these smaller racers, her design an evolution of past Twelves with innovations including its “coffee grinder” winch and stainless-steel shrouds.

“Please don’t every let her go,

there is no second Vim and she needs you”

It’s tempting to wonder what would have become of Sopwith’s (and Fairey’s) racing exploits were it not for the war, but the reality is America firmly had the upper hand by then.

“Why not admit it?” asked John Scott Hughes, author of the 1939 Picture Post spread. “Our American friends are, by and large, the most accomplished yachtsmen in the world. That, really, is the entire explanation of why we have never recovered from them the America’s Cup, lost to them nearly 90 years ago.” American designers, crew and owners – influenced in no small part by Sopwith and Fairey’s aviation input – had won.

Young American designer Olin Stephens, who’d go on to dominate the America’s Cup for decades to come, shaped Vim to be slightly longer, her aggressive hull tank-tested to cut through the water with a fuller shape.

Overhangs were shorter; the maximum beam greater. The wheel and binnacle formed one simple, efficient unit. Great care was taken to simplify all manoeuvres. The cockpit was dry, and spacious (certainly by English standards). Though disqualified on that sparkling day in 1939 covered by Picture Post, she practically left her rivals for dead in the following races, ending the English season with 19 victories out of 28.

Patrick Howaldt, a Danish-resident German national whose grandfather sailed in the 1936 Olympics, had been pursuing Vim for more than a decade when he finally acquired her in 2014. “I used to dream about it,” he says. More recently, he’s been instrumental in reviving Twelves racing in the Baltic under the aegis of the International Twelve Metre Association.

“I came close to acquiring Vim from the Rusconi [Italian media] family in 2006, but evidently it wasn’t to be at that time. Then, in 2012, I hired an Italian captain, Andrea Proto. One year, at the Naples regatta, I shared with him my quest; Andrea was very engaged. With his support, and the offer of a higher price, I finally came to own this fabulous yacht.” Howaldt’s success pursuing Vim has additional significance because the Rusconi family owns Tomahawk. She has spent the last few years out of the water – at least, not racing.

Howaldt’s approach appears to offer a blueprint of sorts to a possible buyer of Sopwith’s former Twelve. “I sense they felt Vim would be looked after and have a good home,” he offers. (Reuniting Sopwith’s Twelve with her mothership is less likely, if not impossible, however: superyacht Philante is now the King of Norway’s Royal Yacht, Norge.)

“The day I signed the contract at the Sangermani yard in Lavagna, I raised a glass of champagne with [captain] Andrea and Sönke Stich of Robbe & Berking,” Howaldt continues. “After the restoration was finished, I received a WhatsApp from John Lammerts van Bueren, the classic boat expert and close friend of Stephens. When I opened the message, I felt a thud in my chest: ‘Just walked by Vim again. I hope you know that Olin would be mighty pleased to see her in such immaculate shape, to see her the way he designed her. Please don’t ever let her go, there is no second Vim and she needs you.’ It was so affecting, this incredible racing heritage speaking so directly to me.”

KEN BEKEN OF COWESEvaine in 1958

KEN BEKEN OF COWESEvaine in 1958

After the UK declared war in September 1939, yachting became impossible off Britain’s south coast. Sopwith and Fairey were consumed by the war effort anyway. “The Fairey Swordfish is to the Royal Navy what the Supermarine Spitfire is to the Royal Air Force,” wrote Adrian Smith, and Sopwith’s Hawker Hurricane accounted for even more kills than the Spitfire in the ferocity of the Battle of Britain. These were the planes that helped repel attacks on the crucial North Atlantic convoys, and helped prevent the Nazi invasion of Britain.

“My great regret in life is that I didn’t bring home the America’s Cup; I really ought to have done”

The rivalry between the two aviators propelled them to ever greater achievements – to the benefit of all – yet left ample room for cooperation, neighbourliness and friendship. They ended up as earthly neighbours on the south coast where Fairey acquired Bossington Estate, 10 miles inland from the Solent, and Sopwith moved to nearby Compton House, having discovered the appeal of the Test Valley after Fairey invited him for a day’s shooting (striking, given the fate of Sopwith’s father).

IMAGEBROKER.COM - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOSopwith’s Camper & Nicholsons Philante, now Norge

IMAGEBROKER.COM - ALAMY STOCK PHOTOSopwith’s Camper & Nicholsons Philante, now Norge

Their later life regrets ran, tellingly, to yachting. Fairey’s daughter wrote in 2017: “One of his great regrets was never having taken Evadne to the Galápagos Islands as Tommy Sopwith had done with his motor yacht.” Fairey sold Evadne (now Marala) “almost by default”, his daughter recorded: “he quoted an impossible price to an importuning potential purchaser, who to his horror accepted. It was a move my father deeply regretted.”

His Twelve, Evaine, did remain in the family until he died in 1956, after which she served as a pacesetter for another attempt at the America’s Cup, in 1958. At least 12 Metre America’s Cup racing, for which Fairey had lobbied long and hard, came to pass. It lasted all the way until 1987.

TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY - GETTY IMAGESSopwith developed a deep-seated urge to achieve

TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY - GETTY IMAGESSopwith developed a deep-seated urge to achieve

In 1988, on his 100th birthday, Sopwith received congratulations from presidents and prime ministers. What was he left yearning for, in the end? “My great regret in life is that I didn’t bring home the America’s Cup; I really ought to have done and I ought to have been allowed to do it,” he said.

Perhaps his rivalry had been less with Fairey, more with himself. Either way, it’s no wonder that these remarkable yachts, first racing nearly a century ago, have become so coveted today – or that there’s been such a renaissance of wider interest in them, evidenced by Evaine’s rejuvenation. Her restoration will take until 2026, at which point she can be fully reunited with her superyacht mothership. And, yes – race.

First published in the June 2025 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.