A CHALLENGER SPIRIT

The remarkable story of Shamrock V and the tea magnate who changed yachting forever

A “down to the last bolt” restoration of J Class Shamrock V, the America’s Cup challenger, has cast a fresh spotlight on Sir Tommy Lipton, her original backer. Who exactly was he, and why is he so enduringly relevant? Daniel Pembrey finds out

JAMES ROBINSON TAYLOR

“We love you, Sir Tea!” cried female crowd members as a wave of excitement coursed through them. Sir Thomas (Tommy) Lipton had appeared on the promenade deck of his 80-metre steam yacht Erin in New York Harbour, ready for another tilt at the fabled America’s Cup.

“True sport,” and “brick!” came deeper-voiced calls from those massed before him, as he waved back in turn, his blue eyes sparkling. He just had such an easy smile, and looked so comfortable with his moustache, cap, white trousers and blue yachting jacket.

A century later, comparisons can be drawn with Bernard Arnault’s youthful grin or Elon Musk’s more Sphinx-like demeanour, yet Lipton was a true one-off. He bestrode the continents, centuries and social echelons as a self-made billionaire (in 2025 money) who’d risen from grocer’s son in Glasgow’s slums to become a global tea titan and friend of monarchs and presidents. “Sir Tea” was an avowed ladies’ man, lifelong bachelor, workaholic, adventurer, tireless innovator, original business celebrity and pioneer of modern sports sponsorship.

GEORGE RINHART/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES (Left to right) Inventor Thomas Edison, Sir Thomas Lipton, steel magnate Charles Schwab and car manufacturer Henry Ford at a dinner for industrialists at New York’s Hotel Astor in 1928

GEORGE RINHART/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES (Left to right) Inventor Thomas Edison, Sir Thomas Lipton, steel magnate Charles Schwab and car manufacturer Henry Ford at a dinner for industrialists at New York’s Hotel Astor in 1928

“His genius lay in telescoping together his personal and business brands, allowing him to promote his consumer products while not being seen to do so,” says the founder of a global communications firm and one of the world’s leading strategists in this field, who, in 2021, acquired Shamrock V, Lipton’s last challenger for the Cup.

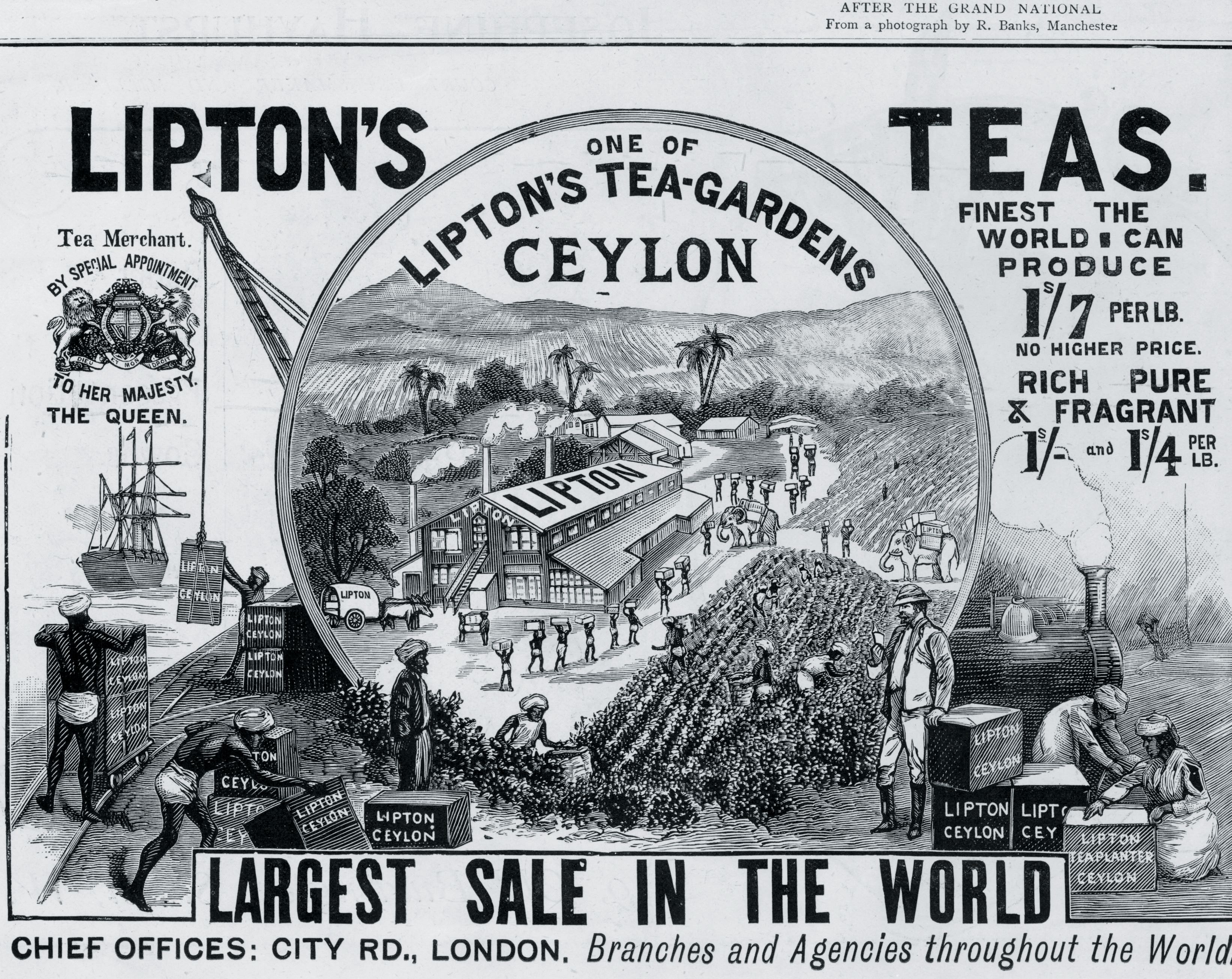

HULTON-DEUTSCH COLLECTIONS:CORBIS:CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES A sample of Thomas Lipton’s advertisement for Lipton’s Teas

HULTON-DEUTSCH COLLECTIONS:CORBIS:CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES A sample of Thomas Lipton’s advertisement for Lipton’s Teas

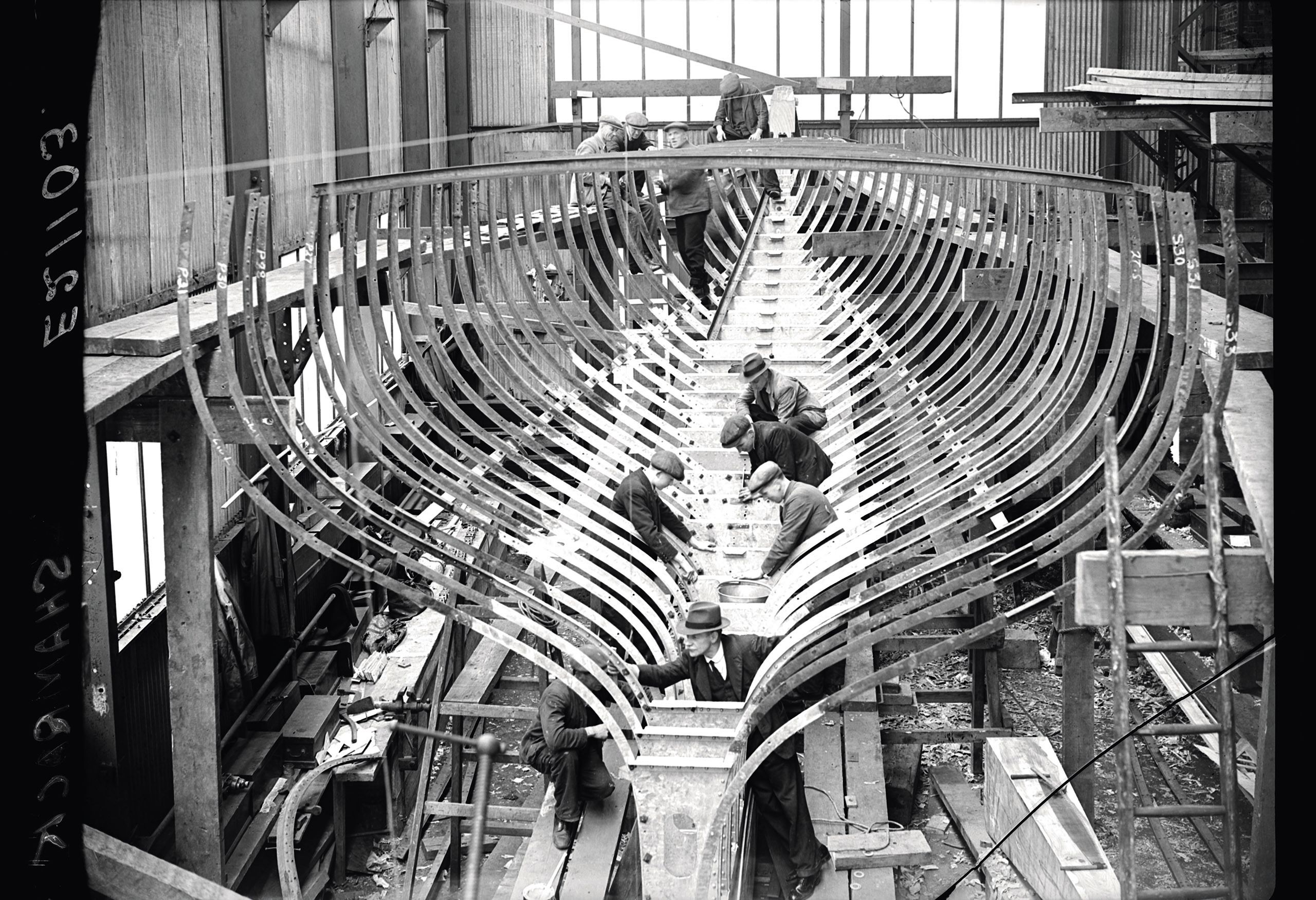

Just 10 J Class yachts were made: six in the US; four in the UK. Only three remain intact, of which two were resurrected from long-derelict hulks – Endeavour, in 1989, and Velsheda, in 1997. Shamrock V, launched at Camper & Nicholsons in 1930 and widely known since as “the Queen of the J Class”, is the only one built in wood as well as the only one never to have fallen derelict. Her acclaimed revitalisation on the south coast of England, completed this summer, sets new standards in historic yacht restoration. Reassuringly, its cost exceeds the sum invested in her original construction.

KOS PICTURE SOURCE LTD: WWW.KOSPICTURES.COM The original J Class yacht Shamrock V in 1930 at Camper & Nicholsons in Gosport

KOS PICTURE SOURCE LTD: WWW.KOSPICTURES.COM The original J Class yacht Shamrock V in 1930 at Camper & Nicholsons in Gosport

“It has been a massive undertaking and a huge privilege to unite extraordinary talents across the classic and superyacht communities,” says Paul Spooner, who, alongside Feargus Bryan, led the project team. “We were very fortunate to have such a committed and knowledgeable owner who enabled us to fully and correctly restore this vital part of yachting history and prepare her for her next 100 years.”

Lipton first sailed to America aged 18, in 1866 – the year of the Great Tea Race. Fabulous, near-mythic, many-sailed clippers hurried their prized cargoes from China, competing to land the new season’s crop in London before others did.

Lipton crossed the Atlantic aboard the slower SS Caledonia sailed steamship, amid the bawdy singing and spewing in steerage, but America opened his eyes, not least to new sales techniques. Back in Glasgow, he reinvented his parents’ single-shop grocery business. A first step sounded simple enough: hanging a sign outside. He used a sizeable one cut in the shape of a ham, painted with such precision that it appeared real.

Installed one hot summer day, at a time when hunger was commonplace, the paint softened and ran just enough to lend the illusion of a freshly cooked ham glistening in its juices. It was an early lesson in the value of verisimilitude (his other initiatives included stocking jumbo cheese rounds wheeled in between gathering crowds and attempts at dropping advertising leaflets over the blustery city from hot air balloons).

BETTMAN/GETTY IMAGES Sir Thomas Lipton

BETTMAN/GETTY IMAGES Sir Thomas Lipton

BETTMAN/GETTY IMAGES With Lord Inverforth, pulling in the mainsheet during one Cowes race won by Shamrock

BETTMAN/GETTY IMAGES With Lord Inverforth, pulling in the mainsheet during one Cowes race won by Shamrock

He wasn’t averse to using sharp business practices. The US became a necessary source of supply to his burgeoning general retail chain (which, by the late 1880s, was reckoned to be the largest in Britain or the US), and he invested in the cut-throat world of Chicago meatpacking, where he was swept up in a price-fixing scandal.

He would also rely on effectively forced labour in the Ceylon plantations supplying his bright rich tea, plus his company would be caught making bribes in the Maltese corner of the British Empire: all standard practices, said his defenders. According to a Chicago newspaper, Lipton showed how “a man who has cornered the pork market need not be hoggish”.

This was the Gilded Age, bringing with it a whiff of decadent, monopolistic corruption in America, and increasing class division across Britain, not to mention growing unease over the British Empire’s Boer Wars. Americans were sympathetic to the underdog Boers, many of whom were farmers armed with hunting rifles.

Lipton cut a reconciling figure, with his own underdog backstory. In Britain, his bushily moustached face and reassuring signature already graced his products (“Not genuine without this signature,” they carried). He was especially alert to the pulse of immigrant and blue-collar America, playing up his Irish ancestry there. His parents had emigrated to Glasgow during the Great Famine in 1847, a year before his birth. The Irish shamrock became his symbol; green and gold, his colours.

Now a man of vast means, he let his philanthropic ventures be known. For QueenVictoria’s 1897 Diamond Jubilee, he “anonymously” arranged a paupers’ banquet for 360,000, all too aware (given his childhood memories) of the results: “Half-famished people devouring the only good meal thousands of them had had in years, and that some had ever had...”

It endeared him to the royal family, earned him the nickname “Jubilee Lipton” and led him to be knighted the following year. But it went down especially well in the US. Less interested in the pomp and circumstance of the jubilee event itself, American newspaper readers latched onto this underdog millionaire who’d suddenly fed the poor. A name seen above Chicago packing houses and on railroad cars suddenly came alive, in the figure of this warm, sporting man, levelling the playing field for those less fortunate.

The rules required challenger yachts to be sturdy enough to endure ocean crossings while defenders could be light and zippy in known home waters

NIDAY PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

NIDAY PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

KOS PICTURE SOURCE LTD: WWW.KOSPICTURES.COM

KOS PICTURE SOURCE LTD: WWW.KOSPICTURES.COM

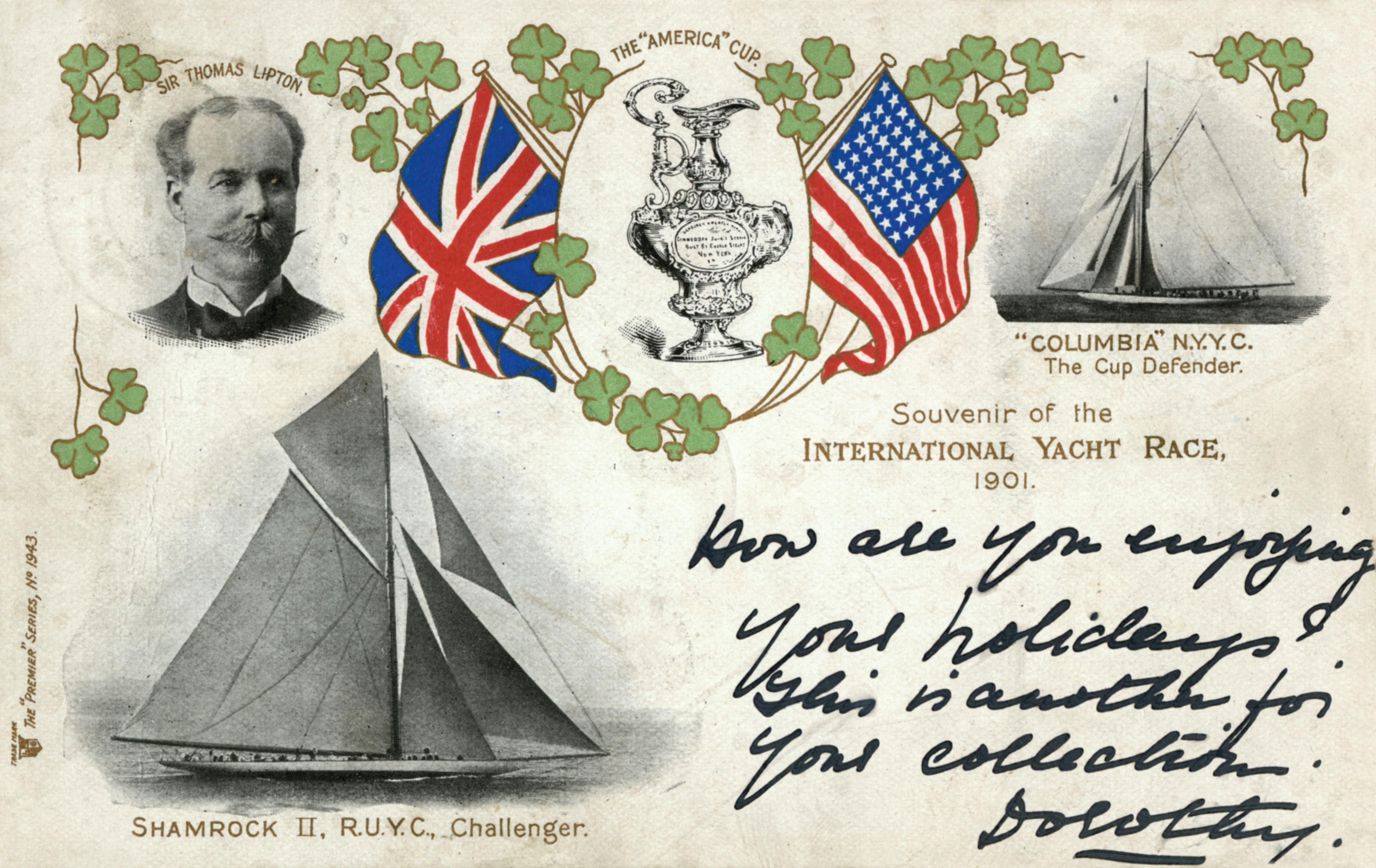

When it came to high-profile sporting events, the America’s Cup stood alone. Lipton first challenged in 1898. The modern Olympics had begun two years prior but no great stars had emerged from it (Coca-Cola wouldn’t partner with it until 1928). Baseball’s World Series hadn’t begun, and the Football World Cup wouldn’t start until 1930, whereas the Cup claimed spectators numbering half a million by the turn of the new century. Avid floating onlookers drew in well-connected visitors, sweeping up the general public too as crowds begot crowds. The spectacle itself became the spectacle.

It had all started unpromisingly enough in 1851 with a race off the south coast of England, bows dipping into the cold waters there, raining spray on decks. The Cup was named after a challenger yacht from the New York Yacht Club (NYYC) that had trounced her British rivals, so much so that when Queen Victoria asked who came second, she was informed, “Your Majesty, there is no second.”

The grinding tectonic plates of American maritime ascendancy and relative British decline could be safely sublimated in this peculiar contest, yet these geopolitical trends didn’t half raise the stakes. The Cup was also a showcase of national technical prowess. On another level, it was plain odd.

The rules required challenger yachts to be sturdy enough to endure an ocean crossing while defenders could stay light and zippy in known home waters. This bias hardly deterred Lipton. Indeed, it was the syndicate members at the NYYC, funding defender yachts, who came to rue the “arms race” of ever-greater spending during his five challenges.

PHILIPP KESTER: ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES On board Shamrock III

PHILIPP KESTER: ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES On board Shamrock III

When invited to complain about the uneven playing field, Lipton scrupulously declined to do so. After his first unsuccessful challenge, a sympathetic lady implored Sir Tea to act on her information that the American side had “put something in the water” to prevent him from winning.

Lipton confirmed that she was quite correct: they had put the defending yacht in the water for that very purpose. As the challenges progressed, local crowds secretly hoped he might win. In a phenomenon finding distant echoes with golfer Rory McIlroy’s quest to win the 2025 Masters Tournament in Georgia, the crowd began to want the British-Irishman to beat the home competition.

And yet Lipton had already won. He’d floated his company on London’s stock exchange in 1898, becoming a billionaire in today’s money. Lipton’s London office alone occupied six hectares of prime real estate on the edge of the financial district of what was then, still (just) the most important city on earth. His business was vertically integrated.

He standardised quality, controlling distribution with shops and branded delivery fleets as well as upstream supply from Ceylon. The beast was thirsty. Thanks in no small part to Lipton, the average Briton drank more than 130 litres of tea a head annually, whereas in the US, that number was negligible. America had the larger population, growing four times as fast. It was becoming richer; more cosmopolitan. It represented staggering untapped potential.

Every time Lipton challenged for the Cup, in his inimitable way, he enticed the US consumer to own a part of his story. Never did he resort to gauche logos or straplines on his beautiful yachts; that was simply not how the Cup was done. Rather, he just presented his tall, square-shouldered, ruddy-faced self. Few, if any, were in a position to do similar. There was Henry J. Heinz, the “Pickle King” of Pennsylvania, clearly unable to challenge. Lipton’s friend Tom Dewar, of the namesake whisky dynasty, barely registered with the US public.

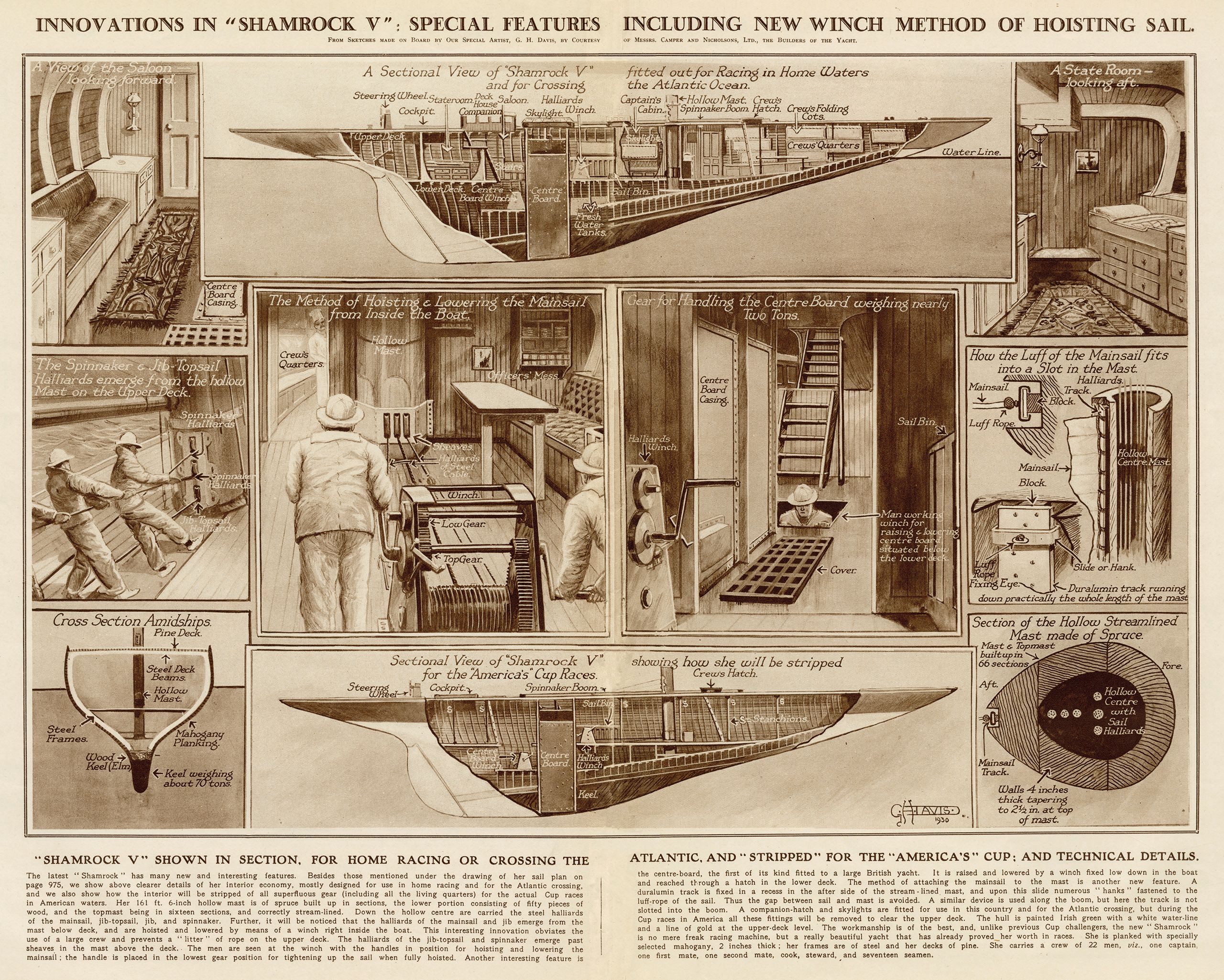

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS/MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY The 31 May, 1930, Illustrated London News article highlighting details of Shamrock V

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS/MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY The 31 May, 1930, Illustrated London News article highlighting details of Shamrock V

General Joseph Wheeler, of the Pilgrims Society (a transatlantic organisation seeking to secure everlasting peace between Britain and the US, supported by clans Astor, Gould, Schwab etc), called Lipton “the most prominent and conspicuous individual on the face of the globe.” It is hard to overstate his fame, then, with his signature way of removing and replacing his cap.

Perhaps only Churchill and The Beatles would contest him for British renown in the US, in the end. Lipton “elevated the standard of Anglo-Saxon manhood”, marvelled Wheeler. He never failed to “read the room”, finding the right words for any occasion; for example, telling an East Coast audience that British tea had been thrown into Boston Harbour because it wasn’t Lipton’s.

“You Americans are hard to beat in any line,” he conceded after losing yet another challenge. “Still, it is a consolation to know that the conquerors belong to the same good old race, who are bound to us by the closest ties. The Cup is still in the family, and is simply held by a more ‘go ahead’ branch.”

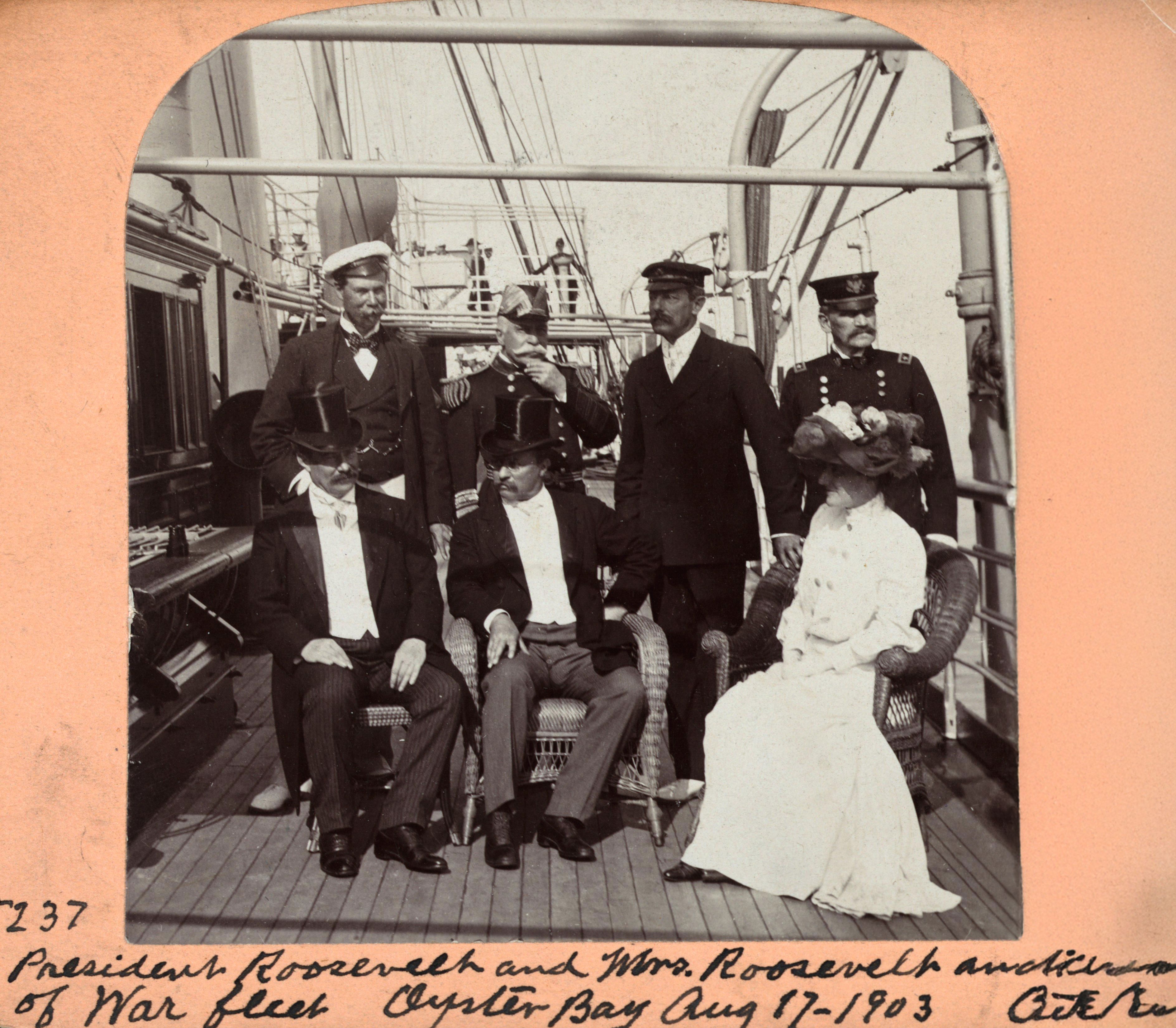

WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO With President Roosevelt aboard Mayflower

WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO With President Roosevelt aboard Mayflower

This family tree metaphor made him a generous uncle, if not a father figure. America still deferred to Great Britain over questions of character and good manners. Lipton had become a cherished bridge between two nations; two eras. He reassured Americans that they were the rightful heirs to great traditions and didn’t need to fear assuming their predestined leadership role, which had long been carried by a now fading empire.

All this informed the way Shamrock V was conceived. As depicted in the Illustrated London News, she looked like she belonged in the previous century, in the best ways possible. Insets showing “A view of the Saloon looking forward” and “A State Room – looking aft” could almost have been the artist’s takes on a country house or London club.

Her lead keel weighed 79 tonnes, and her steel frames were reinforced with a longitudinal trough of steel plates, yet all the visible parts were of fine, trusty wood. Stem, stern post and counter timbers were of teak; the wood at her keel was English elm. The planking was of course mahogany, the main deck laid with yellow pine. The mast – 49 metres tall from truck to heel, and pear shaped in section – was painstakingly crafted from some 50 pieces of silver spruce.

MARY EVANS/GRENVILLE COLLINS POSTCARD COLLECTION

MARY EVANS/GRENVILLE COLLINS POSTCARD COLLECTION

According to Yachting World, the hull of Shamrock V cost £18,000, and her sails, gear and spars another £10,000. Adding the cost of her mast, the total was north of £30,000 – approaching £2 million in today’s money. The bronze and steel hull alone of the defending yacht, Enterprise, cost £50,000.

To this was added the expense of her eight mainsails, 30 other sails, 12-sided aluminium mast, crosstrees, extra masts, a triangular “Park Avenue” boom (so named after the street’s luxurious width), plus extra rigging: a total of more than £120,000 – nearer £7 million now. And she was only one of four contender yachts that the NYYC had backed for the 1930 challenge, in its quest for an unbeatable defender.

SUDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG PHOTO/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO Lipton (left) drinking tea

SUDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG PHOTO/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO Lipton (left) drinking tea

Managed and skippered by railroad scion Harold Vanderbilt, Enterprise became likened to a “robust robot” or a “box of clockwork”. Her Park Avenue boom acquired colour-coded pegs and holes to guide the crew as they attached the sail in prescribed configurations. Winches, used to trim the sails, were located below, clearing the decks.

The 26 crew members were uniformed with different-coloured sweaters and allotted numbers, letting Vanderbilt forget names (when men switched assignments, they exchanged their sweaters and numbers, too). Having worked out any irregularities during the trials against the other three contenders, these men now functioned as a single, machine-like unit.

Shamrock V’s crew remained a cast of characterful, if skilled, individuals. Having lost the first two races, Lipton’s men managed to steal a lead in the third, thanks to near perfect sailing, only for Enterprise to catch up by the halfway point. Just as the contest seemed to become more even, the main halyard securing Shamrock V’s mainsail snapped, sending canvas flapping. Vanderbilt gallantly circled back to ensure no one was in peril or injured. Nobody was, and he coasted to an easy victory.

A tremor of angst rippled through the floating crowd thronging the finish line. “Let him win!” called out some, turning on the elite NYYC victors. Back in Britain, an inquest in the press betrayed a near full-blown identity crisis: “‘New-fangled gadgets,’ we bluster [thundered one yachting correspondent]. ‘Dammit, sir, they destroy the old traditions of the sea. Man power is the right power.’ Blowing out our chests we bawl, ‘one, two, three – pull!’ and haul our sheets in far too flat, while the Americans, Norwegians and Swedes trim their sheets on nice little winches, and sail away!”

Lipton’s success, stateside, was now secure. Prohibition, which started back in 1920, had done his transatlantic tea trade no end of good. It got better: when he’d floated his business on London’s stock exchange, he’d kept hold of his American operation, Thomas J. Lipton, Inc. A year before Prohibition had even begun, he’d opened an 11 storey office and factory across the Hudson River from Manhattan, in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Surmounting it was a big red “LIPTON” sign, visible across the water and from the deck of every ship, and yacht, entering the harbour. The office building even had a lift so large that the car driving Lipton to work could be hoisted to his top floor. There, he occupied the only private space (every other office being partitioned with glass, in an arrangement surely familiar to many workers now), spending all hours of the day analysing reports and giving orders. He, too, knew the value of modern scientific management techniques.

JA HAMPTON/TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY Lipton receives flowers from his godson, Alfred Lipton Bowker, on board the liner SS Leviathan in 1930

JA HAMPTON/TOPICAL PRESS AGENCY Lipton receives flowers from his godson, Alfred Lipton Bowker, on board the liner SS Leviathan in 1930

In the wake of his fifth Cup challenge, he was 82 years old and fading, his bearing now less square-shouldered, his public appearances more rare. The Great Depression would be the biggest challenge to the glorious J’s starring in the Cups of the Thirties, as the mass audience identified less with these elite endeavours. Yet the lore of the event lived on, and would only strengthen down the decades – even as other sports eclipsed it in audience share.

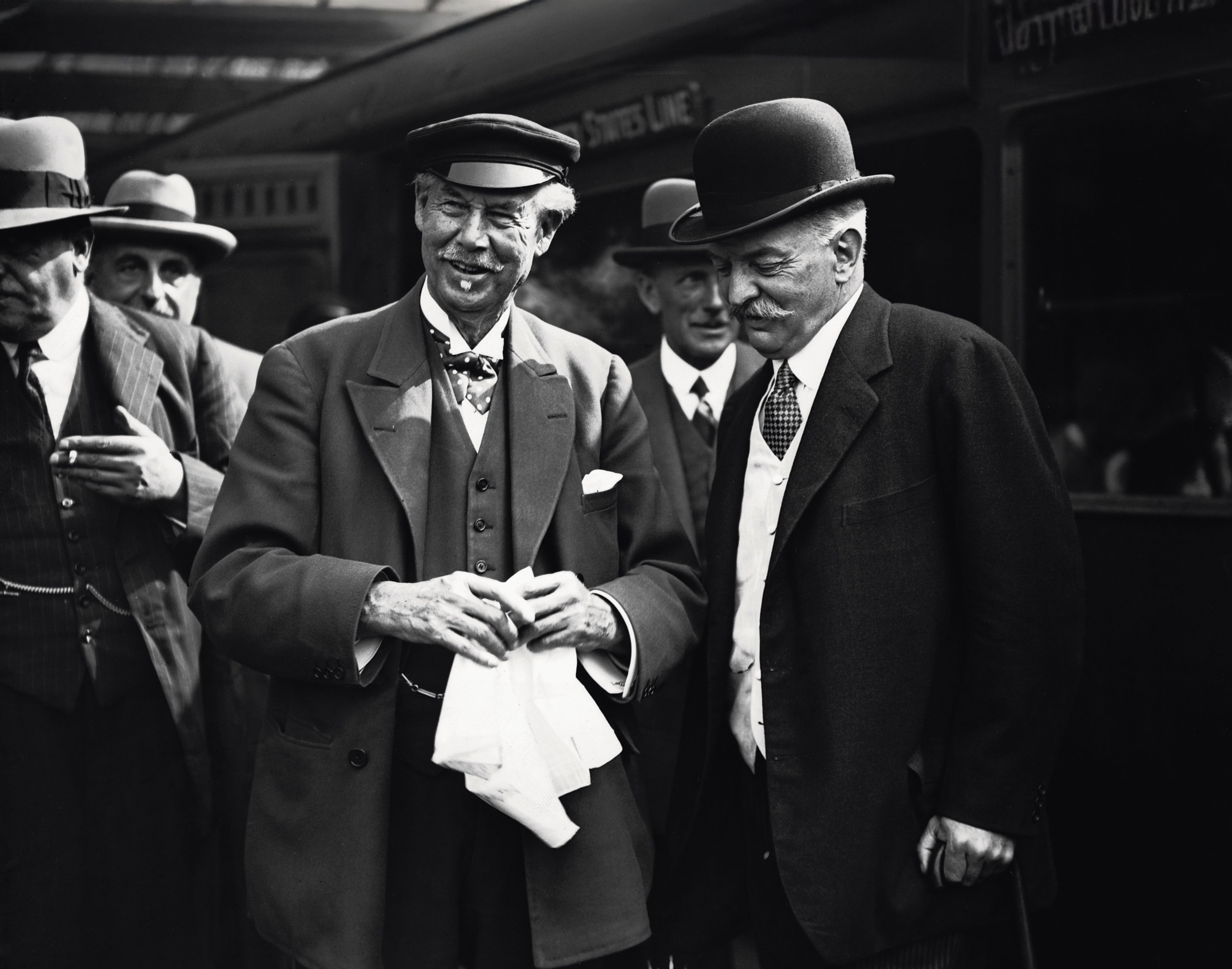

HULTON-DEUTSCH COLLECTION/CORBIS Lipton with Lord Thomas Dewar

HULTON-DEUTSCH COLLECTION/CORBIS Lipton with Lord Thomas Dewar

Lipton died in 1931 with no offspring or close relatives. He’d outlived close friends such as Lord Dewar. His worldwide tea brand did succeed him, however. It was acquired by Unilever and more recently spun out to CVC, the private equity firm. Even a century on, mentioning Lipton makes most people think of tea. His name can also be found on innumerable sporting cups and charitable causes, and there are at least two other legacies on which to reflect.

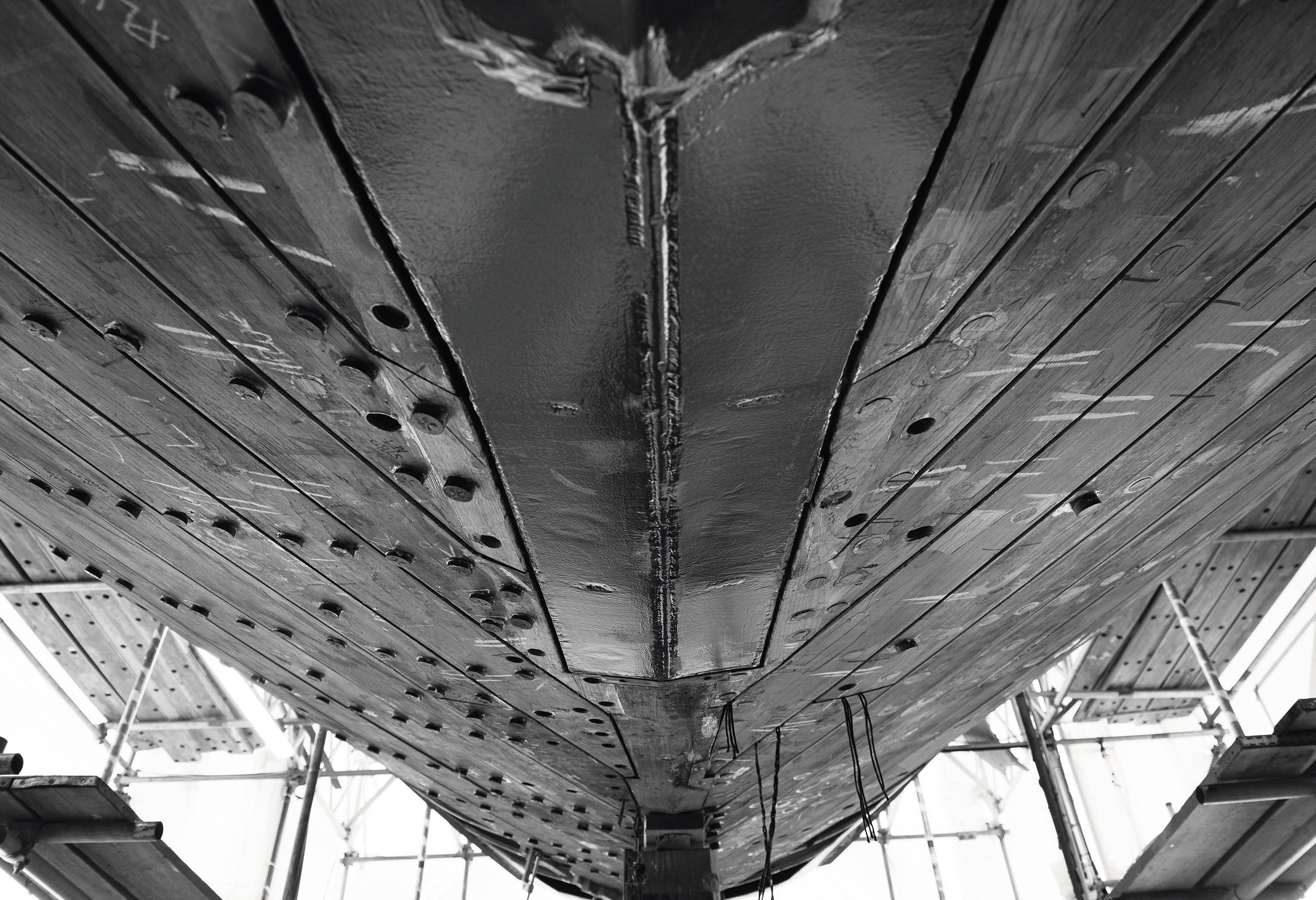

Shamrock V – Lipton’s yachting legacy – is so renowned that the current owner sees himself more as a custodian. When her renovation began, the amount of rot and rust uncovered called for such a major rebuild that it was decided “nothing should be painted over and left for the next guy.”

Some 200,000 craftsman-hours later, 95 per cent of the original teak (from a re-planking in 1970) has been reconditioned and refitted; 62 per cent of her steel frame has been salvaged, strengthened and repainted, and all of the 6,500 bronze alloy bolts holding her together, decayed beyond repair, have been replaced using a factory in the north of the UK, not far from where Lipton started out.

“It’s very rare to be able to work on a revival of this scale and ambition,” says lead shipwright Giles Brotherton, a veteran of several of the world’s most storied classic restorations. “Some of our artisans were using hand tools employed on Shamrock’s original build.”

WATERLINE MEDIA/SHAMROCK V More than 95 per cent of Shamrock V’s original teak was refinished and reused, 6,500 bronze bolts restored and artisans used hand tools from the original build

WATERLINE MEDIA/SHAMROCK V More than 95 per cent of Shamrock V’s original teak was refinished and reused, 6,500 bronze bolts restored and artisans used hand tools from the original build

Crews are being assembled and races envisaged, but with Shamrock V’s marquee heritage status in the Cup’s illustrious history now secured, attention has returned to the main event, and Lipton’s other legacy worth calling out.

After the last, 37th Cup in 2024, the University of Barcelona and the Barcelona Capital Nàutica Foundation conducted an in-depth study of its impact away from the drama playing out on the rippling Spanish waters: €1.4 billion of total gross media brand value, a worldwide TV audience of 954 million, and a host of brands sponsoring it, with Bernard Arnault’s Louis Vuitton claiming the title partnership.

The 2024 America’s Cup Event CEO, Grant Dalton, remarked: “The 37th America’s Cup will be remembered as one of the best yet, and one that continued to build the commercial strength and audience of the widely recognised pinnacle event in sailing.” Doubtless Lipton would have raised a tankard to that in his own avuncular way – or reused one of his most telling off-the-cuff remarks when asked about his success: “The secret of it? Make no secret of it. Advertise all you can.”

First published in the September 2025 issue of BOAT International’s Life Under Sail. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.